Writer and stand-up comedian Anuvab Pal held a humour workshop with children between the ages of 8-14 recently, at the end of which they had to perform a stand-up comedy show with material they wrote themselves

Writer and stand-up comedian Anuvab Pal held a humour workshop with children between the ages of 8-14 recently, at the end of which they had to perform a stand-up comedy show with material they wrote themselves. As part of the performance, they were asked what their biggest problem was and they all agreed on “old people.”

Writer and stand-up comedian Anuvab Pal held a humour workshop with children between the ages of 8-14 recently, at the end of which they had to perform a stand-up comedy show with material they wrote themselves. As part of the performance, they were asked what their biggest problem was and they all agreed on “old people.”

ADVERTISEMENT

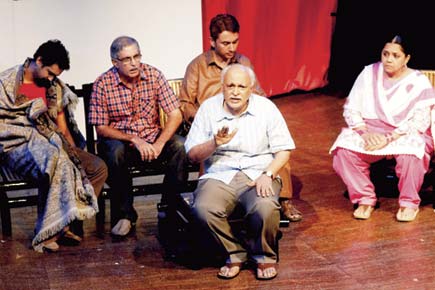

A scene from the play Black With Equal at the NCPA Cheer Festival 2015 at Tata Theatre, NCPA

It was startling to discover that kids find senior citizens a nuisance, more so to find that who they consider old are probably people in the prime of their lives. One kid grumbled, “Old people are boring,” another that they “walk too slowly.” Many of them had a grouse against grandparents who were not updated with the latest technology and it fell on the kids to teach them how to use computers and mobile phones, and the seniors were not quick learners. One of them had to teach his grandmother over and over again, “and it was not even a smartphone,” he groaned impatiently.

They hate the shows their grandparents watch on TV, they don’t like to be nagged about studies, or food choices; scolded over eating popsicles or walking too fast. A few kids talked of being seated next to “old people” on flights and being annoyed with questions, pulled into conversations they found dumb, or didn’t want to have in any case. “They take more interest in our lives than their own,” a child ranted.

Another child declared, “Old people have no idea of the world, no idea of technology. They should get on with their lives and stop irritating us.” This was all in jest, but what if this is what kids really think of the elderly?

All this while, children got along with grandparents and saw them as a shield against parents’ scrutiny. When did it happen that kids started seeing grandparents as irritants and their loving curiosity or expressions of affection as interference? Is it that they are influenced by the rampant ageism around them? Children are like sponges who absorb the good with the bad, and don’t often have the filter to help them decide what to retain and what to eject. If they see around them a society that has no respect or warmth towards the elderly, that’s the behaviour they will emulate.

The other thing many kids found aggravating was being taken to family weddings. They said they hated wearing scratchy clothes and having to dance. Time was when kids liked to go to family gatherings and hang out with cousins, friends and have a good time. Now they’d rather be left alone with their TVs, tablets, smartphones, gaming consoles. Are parents raising a whole new generation of unsocial loners? It’s a worrying sign.

It’s not directly connected, but prejudice and suspicion of the ‘other’ is at the core of Vickram Kapadia’s play Black With Equal, that he has revived after a decade. In the interim, our society has become even more narrow-minded and bigoted. Minorities, singles, non-vegetarians are not welcome in many buildings, and gone is the secular ethos that defined community living in Mumbai.

In the play, the innocuous annual general body meeting at the home of the building’s secretary (Utkarsh Mazumdar) explodes into hatred and violence. The society in suburban Mumbai is a mixed one, with a Sikh (Kapadia), a Parsi (Dinyar Tirandaz), a Christian (Daniel D’Souza), two Muslims (Suhita Thatte, Jaimini Pathak), a single woman (Seema Mishra) and a gangster (Jayesh More), who is a law unto himself, with alliances nobody dares question.

On the surface they are all friendly and pleasant, but the slightest push and their deep-seated biases come tumbling out. Accusations are flung about in anger, and suspicions aired. In no time, the pretense of good neighbourliness and civility evaporates — this is something we see all the time when a friend, neighbour or even stranger is suddenly no longer an individual but a part of a tribe called “you people.”

Everybody will see a reflection of themselves in the play or recognise people they know — every Mumbai resident has seen a general body meeting degenerate into chaos.

Kapadia’s satire hits harder now than it did earlier, because of how rapidly our society has been fragmented. The play also suggests that a crisis or an all-out war-like situation unites the squabbling people again, but should we wait for things to fall so completely apart before we start picking up the pieces, or should we prevent the rupture before it’s irreparable?

Deepa Gahlot is an award-winning film and theatre critic and an arts administrator. She tweets at @deepagahlot

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!