In his most recent outing, Babroowan Rudrakanthawar — a fictitious cartoon character created by Aurangabad-based journalist-writer Dhananjay Chincholikar — joins friend Dost in the search of an aam aadmi fit to be a politician

Egoistic manasala lai avgad jata Facebookvar. Ithe public jumanat nahi konala… direct express vhatet… practicalmandi aadat nastiya asa aikun ghenyachi...

Egoistic manasala lai avgad jata Facebookvar. Ithe public jumanat nahi konala… direct express vhatet… practicalmandi aadat nastiya asa aikun ghenyachi...

ADVERTISEMENT

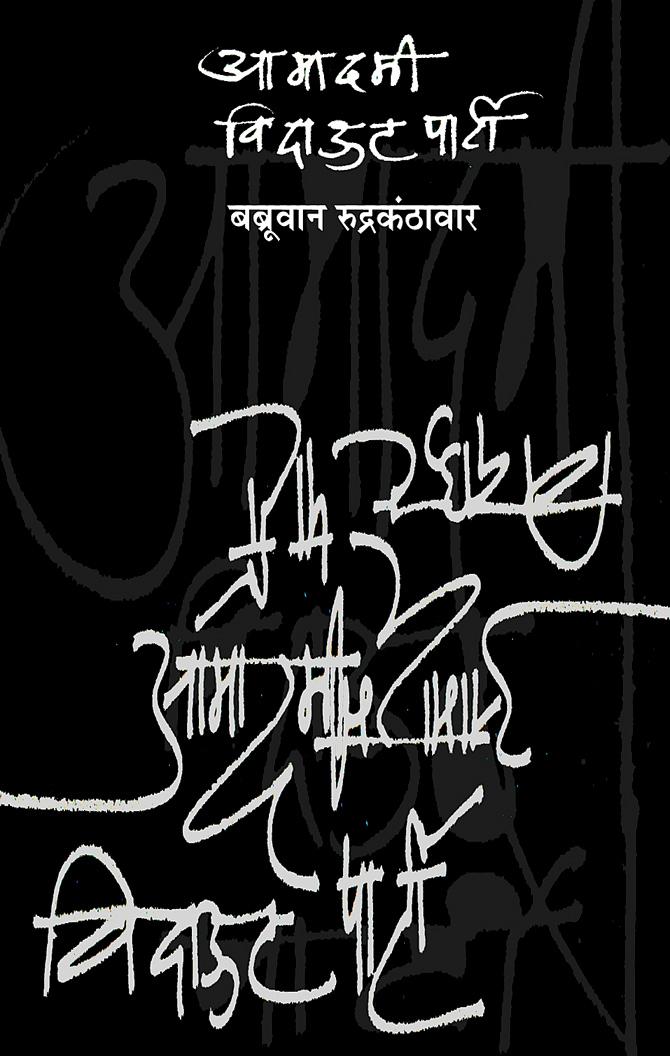

This is no gibberish, but a user alert to sensitive virtual media enthusiasts who cannot digest criticism in real life. Presented in a spicy cocktail mix of English words and a conversational idiom from Marathwada, the advisory comes from a writer named Babroowan Rudrakanthawar in his just-released book, Aamadmi Without Party. While this is Babroo's fourth anthology of essays on sundry subjects — WhatsApp-addicted children, PR-driven legislators, and rent-a-quote thinkers — he maintains that the English-Marathi fusion is not a consciously chosen literary device. It is Babroo's true-to-life everyday gramin boli (rural parlance) spoken by common people of the Marathwada region; an internalisation of a foreign language with its own emotional architecture.

Babroo's linguistic style and identity is about two decades old. He was born sometime in 1998 when Aurangabad-based journalist-writer Dhananjay Chincholikar (50) assumed the mythical persona of Babroowan Rudrakanthawar in the book Punyanda Chabdhab (Meddling Again). Chincholikar created Babroo as a 30-something small-time scribe who shares his intimate political and philosophical thoughts with a friend named Dost.

He has a son named Gabroo, who is as old and ill-mannered as Dost's brat. Both friends' wives (and children) have sharp tongues and razor-sharp minds. Babroo's take on life comes from his experience as a hack; the Dost has dabbled in zilla parishad level politics from where emerge his musings on corruption and accountability. With no big stakes to bother with, together they thrash out every problem of the day — new-age parenting to caste divisions, ecological imbalance and middleclass angst to reality show gimmicks.

Ever since Chincholikar's first book unfurled the Babroo brilliance, the reader witnessed a chronological progression in the narrative. The once-young Babroo and Dost are now in their fifties. Their children, hooked on to Shin-chan, have grown into aggressive Facebookers.

Babroo's progression is also manifest in terms of the subjects. In Chincholikar's Bertrand Russell With Deshi Philosophy (2007), Babroo applies the British philosopher's dictum (Children's bad habits are perpetuated by punishment, but will pass away if left unnoticed) while dealing with Gabroo's nose picking routine. He quotes Russell's take on publicity tricks while analysing local media practices. In Tirya, Dingya aan Gale (2012) meaning 'Bluffs, Boasts and Bawling', Babroo comments on the masks (necessitated by a swine flu scare) as against the facades required in everyday life. He recalls Maharashtra politicians' nostalgia for slaps which ensure publicity. In keeping with the 2012 political climate, Babroo elaborates on the competition amongst political outfits over burning of opponents' effigies.

In Aamadmi Without Party, the impetus is Babroo's quest for a common man candidate for Dost's party. Dost has loaded many specifications into the search, as his party is seeking an all-rounder aam admi who is active, social, one with a political nose, and no established party affiliation, neither Left nor Right. Dost notifies: "Amhala pahije Professional Aamadmi without cap... regular nako..." The cap flashing a slogan denotes arrogance.

Chincholikar says Babroo and Dost lead lives just like any Aurangabadkar would do. "I find it difficult to tell readers, more from the cities, that such conversations do take place and in the same flavour. People find the English words funny, but that's because they can't guage the massive impact of English on the rural mileu..." The writer feels the rural-urban divide has disappeared with regard to the penetration of English language. He says his books neither dismiss nor praise the kitsch lingo, but just tell it like it is.

Chincholikar's Babroo now has a busy cultural calendar, which transcends Aurangabad. His wisdom and political nuggets have followers on Facebook and the demand for Babroo gyan is evident in the sale of the book across Maharashtra. Aamadmi…'s Aurangabad-based publisher Janshakti Vaachak Chalwal is excited about the praise showered by the literati, as reflected in the foreword of Simhasan fame editor-writer Arun Sadhu. Cartoonist Anil Dange's black-and-white tableau beautifully captures the Babroo clan.

Babroo's humour is not rib-tickling or a forced play of words. It has an elasticity that gels with the distinctive Marathwadi twang. When a similar synthesis has been attempted in Marathi mass media, it has failed and invited censure (especially after Marathi became a classical language) because the standardised usage and grammar has legitimacy in a formal space. But Babroo's cosmos permits experimentation. It is rooted in small-town rural Maharashtra (Marathwada being emblematic) which is fast losing its indigenous expression. Writer Chincholikar shares the so-called rural landscape and uses Babroo as a vehicle. The underlying parody in each anecdote demonstrates the fast-Westernising rural India. For instance, in the Do or Dye chapter, Dost justifies his right and duty to henna his wife's hair.

In 'Some Text Missing', a character evolves the skill of eating (muting) potential provocative words half-way before enunciation.

Aamadmi... seems a conglomerate of whacky characters. On a closer look, they are people with unique coping strategies — the DTP operator who relies on the tobacco stock dribbled in his keyboard crevices; an office boss who forces the no-milk tea down his staff's throats; an exploited speech writer who wreaks a unique revenge.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!