Chhello story of light

Updated On: 23 October, 2022 07:20 AM IST | Mumbai | Meenakshi Shedde

Ironically, Chhello Show, shot in glorious 1:2.35 ratio or ‘Cinemascope’ (think Sholay), is a tribute to celluloid film that was shot digitally on an Arri Alexa

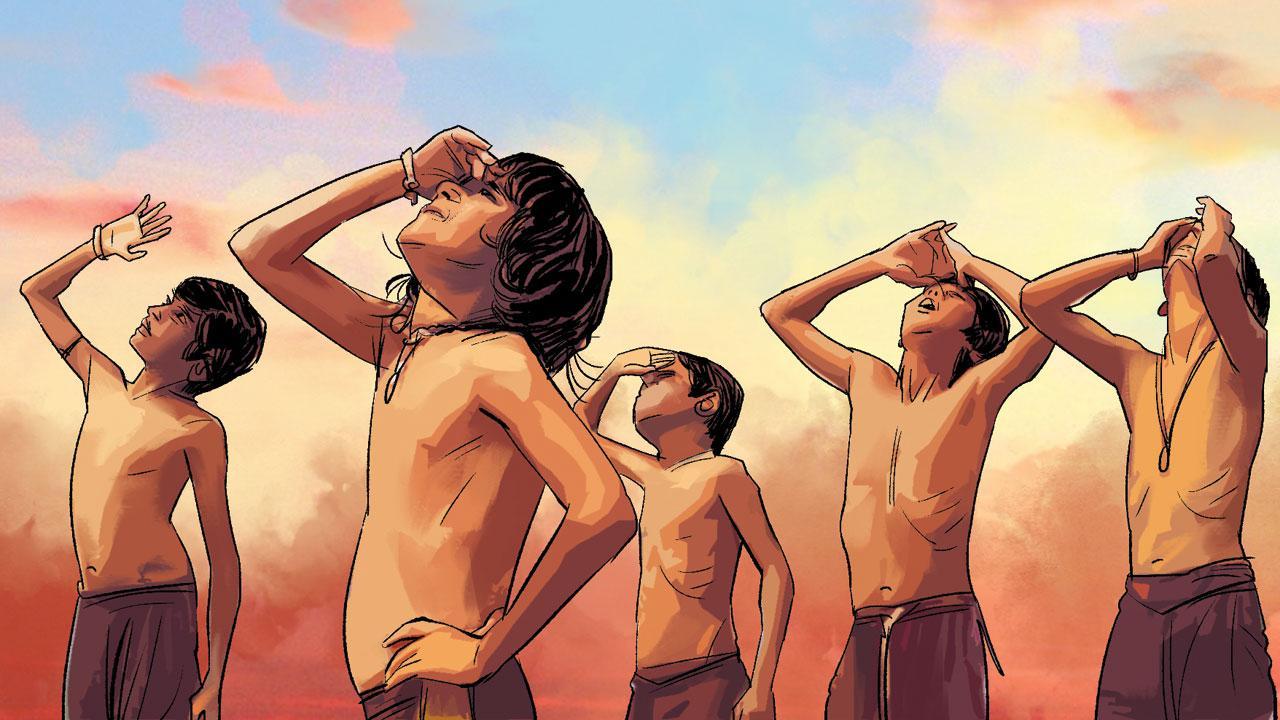

Illustration/Uday Mohite

![]() Pan Nalin’s Chhello Show (Last Film Show, an Indo-French collaboration in Gujarati), India’s entry for the Oscars, is a nostalgic love letter to cinema, as seen on nearly-vanished, 35-mm celluloid film, in single screen cinema theatres. It’s a coming of age drama that was at the Tribeca and BFI London Film Festivals. Perfectly timed, as exhibitors try to lure OTT-addicted audiences back to the theatres with the magic of the big screen, the film is now running in all-India cinemas. Tragically, there’s hardly any public cinema in India regularly showing 35-mm celluloid prints, apart from the National Film Archive of India theatre in Pune, or similar. Ironically, Chhello Show, shot in glorious 1:2.35 ratio or ‘Cinemascope’ (think Sholay), is a tribute to celluloid film that was shot digitally on an Arri Alexa.

Pan Nalin’s Chhello Show (Last Film Show, an Indo-French collaboration in Gujarati), India’s entry for the Oscars, is a nostalgic love letter to cinema, as seen on nearly-vanished, 35-mm celluloid film, in single screen cinema theatres. It’s a coming of age drama that was at the Tribeca and BFI London Film Festivals. Perfectly timed, as exhibitors try to lure OTT-addicted audiences back to the theatres with the magic of the big screen, the film is now running in all-India cinemas. Tragically, there’s hardly any public cinema in India regularly showing 35-mm celluloid prints, apart from the National Film Archive of India theatre in Pune, or similar. Ironically, Chhello Show, shot in glorious 1:2.35 ratio or ‘Cinemascope’ (think Sholay), is a tribute to celluloid film that was shot digitally on an Arri Alexa.

Samay (Bhavin Rabari), 9, growing up in Chalala, a small village in Gujarat, bunks school to watch movies at Galaxy cinema. He exchanges his dabba (Lunchbox, remember?) with the projectionist Fazal (Bhavesh Shrimali), who lets him watch films from the projection room. A Gujarati Cinema Paradiso that draws from Giuseppe Tornatore’s 1988 film, it extends the story of a kid and a film projectionist, with a reflection on the evolution of cinema itself.