A recently translated Gujarati novel, set in 19th-century Bombay, sparks a fresh look at literary transferences to English

Woodcut prints by MV Dhurandhar illustrating the Gujarati original

What happens when a two-word expression you grew up giggling at—hearing family elders describe a morose person—presents itself as the title of a classic? The English edition of the Gujarati novel, Dukhi Dadiba, elicited my curiosity, followed by a wonderful read.

What happens when a two-word expression you grew up giggling at—hearing family elders describe a morose person—presents itself as the title of a classic? The English edition of the Gujarati novel, Dukhi Dadiba, elicited my curiosity, followed by a wonderful read.

ADVERTISEMENT

Seasoned translators, Aban Mukherji and Tulsi Vatsal have remarkably captured the consummate artistry with which the author of Dukhi Dadiba, the prolific Dadi Edulji Taraporewala (1868-1914), etched credible characters and placed them in upper-class Parsi society of late 19th-century Bombay. The narrative involves a mysteriously missing scion, a heroine grappling with the age-old dilemma of marrying for love or money, other women characters unusually spirited for their time and milieu, and exciting courtroom drama for a finale.

Specialist litterateurs, across the genres of fiction, poetry and stage writing, balance views on the pleasures and pitfalls of Gujarati-to-English translation.

Why were you drawn to translating this novel?

Aban Mukherji: A friend came across this book while looking through the belongings of a relative who had passed on. She asked if I would like to have it. I readily accepted, little realising its value at that time.

Tulsi Vatsal: We do not read a book with the object of translating or publishing it. We were drawn to MV Dhurandhar’s evocative illustrations and then found that the (rather improbable) plot, with its twists and turns, as well as the short chapters, made for a quick, entertaining read. The setting of the tale when Indian, especially Parsi, society faced the challenges of Westernisation, added to the appeal.

Aban Mukherji and Tulsi Vatsal, the translators of Dukhi Dadiba

Aban Mukherji and Tulsi Vatsal, the translators of Dukhi Dadiba

What have you collaborated on earlier?

AM: One of our most challenging translations was Karan Ghelo: the last Rajput King of Gujarat. Being the first modern original Gujarati novel (1866), which has never been out of print, we felt very responsible for our translation quality. Working on it gave us tremendous satisfaction.

TV: Apart from being the first Gujarati novel, Nandshankar Mehta’s Karan Gehlo (translated for Penguin, 2015), set in the time of nascent nationalism, tells a story of defeat—of the last Hindu ruler of Gujarat.

Your lively lines keep reader attention close to the narrative. How have you retained contemporary appeal of a century-old text?

AM: Taraporewala’s style being surprisingly modern and straightforward, it wasn’t difficult to visualise his characters and their surroundings.

TV: The key feature of our translation process is reading the original text aloud. This gives a feel for pacing, rhythm and flow. We also read the English translation aloud to see if we have caught the flavour of the original. There is a considerable amount of dialogue in Dukhi Dadiba. Conversations between father and daughter, mother and son should sound as if happening today.

What challenges were faced while translating?

AM: Serialised in the magazine Masik Majah (Monthly Merriment) in 1898, this work was so popular with the public that the magazine sales soared and led to the book published in 1913, a year before Taraporewala died at the age of 46. Serialisation implied a lot of repetition, of almost whole chapters at times. We had to do away with these in a way that did no disservice to the original.

TV: The author obviously felt it necessary to recap and remind readers of past events. Removing the very tedious repetition while making the text flow seamlessly was a challenge.

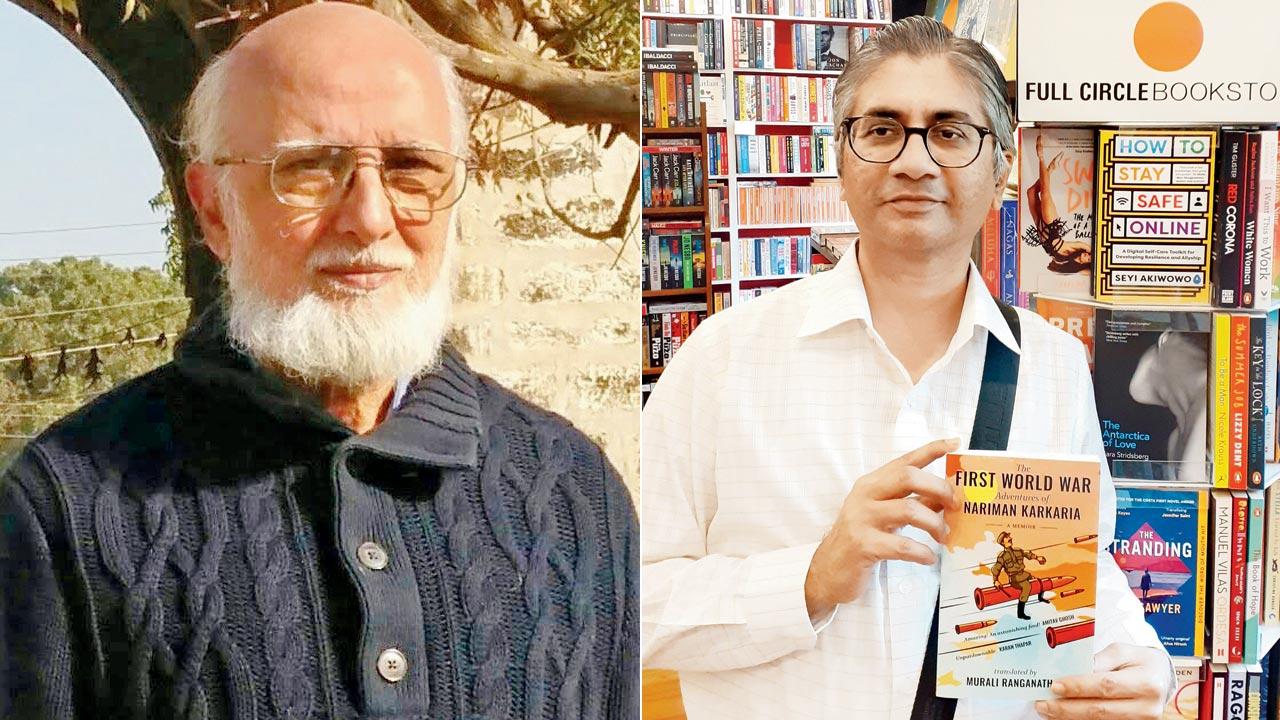

Sitanshu Yashaschandra; (right) Murali Ranganathan, author of The First World War Adventures of Nariman Karkaria

Sitanshu Yashaschandra; (right) Murali Ranganathan, author of The First World War Adventures of Nariman Karkaria

Which real-life characters inspired Taraporewala to “docu-fictionalise” their story?

AM: We have not found anything about the families on which this story is based. I feel the novel should be judged on its own merit.

TV: After checking basic sources, we haven’t been able to find out. It seems surprising that a story concerning two of the most prominent families in Mumbai, a missing heir and a sensational court trial, finds no mention in Parsi Prakash or other sources.

Quotes of Indian saints and poets are interspersed within chapters—incongruous with Parsi authorship?

AM: Taraporewala was a highly educated person, well-versed in Gujarati and even, I think, Marathi literature. It isn’t surprising that he would intersperse such quotes in his Gujarati prose, the style perhaps borrowed from Farsi literature. Parsis then were much more attuned to their Gujarati culture. They thought in the language and composed many works in it.

TV: Yes, educated people in those days read widely and were familiar with Farsi.

Commending Mukherji and Vatsal, poet-playwright and translator Sitanshu Yashaschandra believes Parsi authors contributed the most enjoyable texts in modern Gujarati literature. “Taraporewala describes a culture in transition: 19th-century Bombay, where Parsis were a bridge between aggressive, exploitative colonial rulers and the resilient, clever Hindu-Muslim society. Dadiba is dukhi not only personally, but societally. He and other characters tell their own stories and a larger story: of the fashionable Westernisation of India and assertion of the quietly resistant Eastern culture, helping Dadiba to be sukhi.

“The translation is sensitive to this complexity, lucid and true to the multi-culturality and multi-historicity of the plot. I salute the translators and publisher for keeping the Parsi Gujarati title intact. The graph of the reader’s interest curves upwards as the reading proceeds. With neo-colonial powers on our doorsteps today, the theme of the original book is no more irrelevant. Pareen, Dadiba and Jehangir make a triangle that is eternal and forming anew.”

Yashaschandra has translated his Gujarati poet contemporaries and essays in Gujarati literary criticism. Invited by the Sahitya Akademi to translate his Gujarati poems for an anthology in English, he shares, “How hazardous yet beautiful is the road of self-translation, calling for honed skills and alert self-discipline at their best. The cup never more than the drink, a translation should be nearly invisible, not a self-important language strutting around. Translating into English, I am not doing a favour to the Gujarati author’s work. If at all, it is a gift to those who cannot read Gujarati, but are good at reading English.”

Tonalities differ, particularly in the poetry of the cultures. Yashaschandra likens translating from Gujarati to English (unlike into Hindi) to using an inner audiometer with precision. “A certain English whisper can do the work of a specific Gujarati shout—and the other way round. Syntax differs too. Gujarati in my original poems walks the distances its own way. English, in my translation of my poems, walks quite differently. The routes I choose for my poems in English translation are often deviant from those my original Gujarati poems take to travel towards readers.

“‘Literature’ began being written in English around the 14th century [rather than Latin, as was the practice till then]. The earliest ‘literary’ texts in Gujarati, rather than Sanskrit, appeared in the 12th century. A translator needs to feel proud and confident that the work has a long, strong history. This awareness selects texts for their innate strength, not as samples of exotica for the amused Western reader. Indian writing in English errs the most on this count.”

Translating living authors of Gujarati works, theatre practitioner Naushil Mehta emphasises, “It’s important to have an author freely allow you to express the original’s concerns your own way. Remaining faithful to the text can be detrimental to the project. Taking Gujarati material to English versions, my toughest call is selecting the subject. Not everything travels well into English.”

Mehta’s decision to adapt Madhu Rye’s Gujarati novel, Kimball Ravenswood, into the English play, A Suitable Bride, was a risk in 1996 as Ketan Mehta’s TV series, Mr Yogi, based on the same novel, was already aired. Proving a smash hit in Bombay, A Suitable Bride pulled a memorable performance in Khadakwasla, at the NDA, before 2,500 officer cadets—“The ideal audience for the story of NRI Yogesh Patel come bride-shopping to India,” says Mehta. “Most of those boys might have gone on to undertake Yogesh’s journey in the next few years.”

A colourful 2022 translation is Murali Ranganathan’s The First World War Adventures of Nariman Karkaria. Part memoir-part autobiography-part travelogue, it is possibly the sole trench account by an Indian from 1922, released as a serial in the Jam-e-Jamshed newspaper. Conversant with at least six languages, Ranganathan says, “Living in a cosmopolitan building society in Mulund, as kids we watched great Gujarati and Marathi television shows like Avo Mari Sathe, Kilbil and Santakukdi.” Interpreting the exploits of his Navsari-to-Bombay transplanted protagonist, who survived action on three fronts with a British army regiment, Ranganathan’s biggest task was convincing himself about tackling Karkaria’s Gujarati manuscript without reaching for

a dictionary.

Gujarati was the predominant language of the Parsis till the 1950s. Bombay households read an impressive number of journals in their mother tongue, including Jam-e-Jamshed, Kaiser-e-Hind, Akhbar-e-Saudagar and Mumbai Samachar, the mainstay of every other Gujarati-speaking community.

As Ranganathan said in an interview to Naresh Fernandes of Scroll.in: “All communities were writing but the Parsis took to it aggressively. There were serialised Gujarati translations of Persian classics. The war memoir as a mainstream personal narrative came into being from World War I. Karkaria found willing subscribers for his narrative. Many lost books deserve resurrection in translation.”

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at meher.marfatia@mid-day.com/www.meher marfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!