A new biography on barrister Nath Pai shines light on his complex friendship with political rival Nehru, and how he fought tooth and nail for Maharashtra’s interest in the Parliament

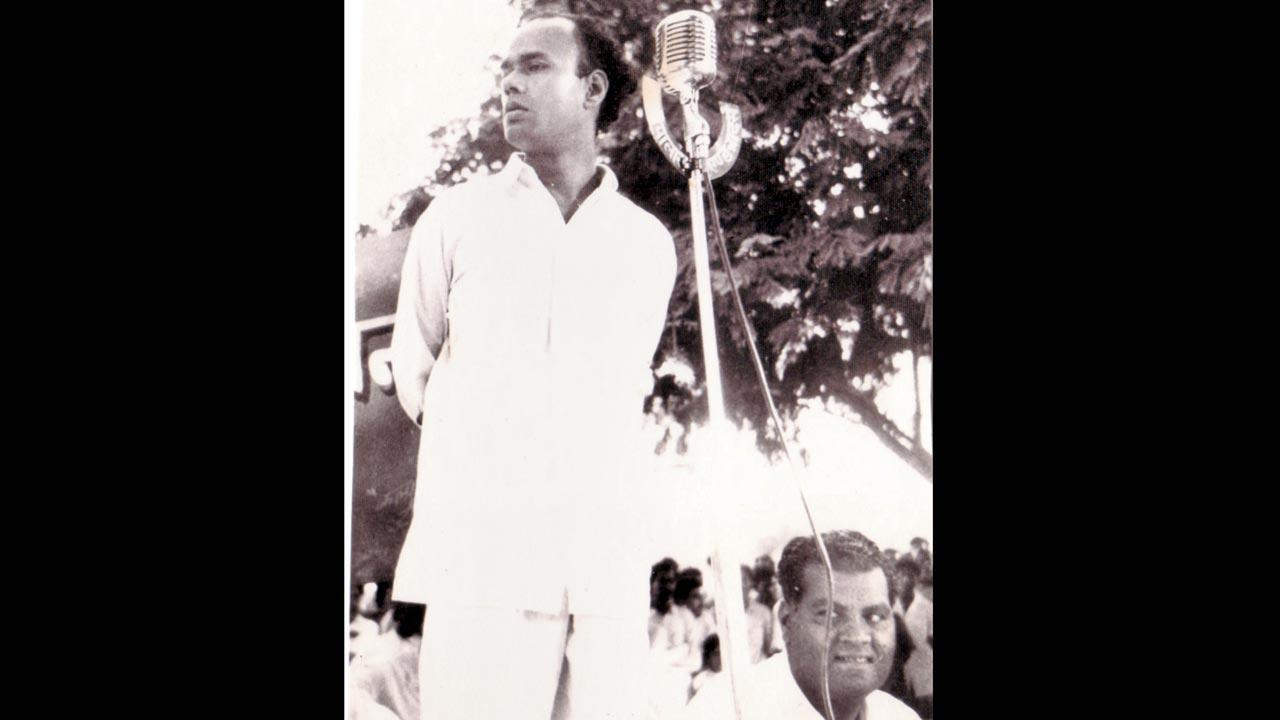

Barrister Nath Pai, elected from the Rajapur Lok Sabha seat on the Praja Socialist Party ticket, was known to be a remarkable orator.

![]() Books offer themselves at interesting junctures. While I was revisiting some commemorative literature on India’s first Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, whose 132nd birth anniversary falls today, I was gifted two paperbacks on a bygone parliamentarian who was called “Nehru’s Nemesis”. Barrister Nath Pai (1922-1971), elected from the Rajapur Lok Sabha seat on the Praja Socialist Party (PSP) ticket, was a remarkable orator whose research-backed speeches (undocumented in video form) shook PM Nehru. Despite being on the opposite side of Pai’s electoral politics, Nehru not just heard the former’s dissenting voice on the floor of the House, but sought Pai’s company.

Books offer themselves at interesting junctures. While I was revisiting some commemorative literature on India’s first Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, whose 132nd birth anniversary falls today, I was gifted two paperbacks on a bygone parliamentarian who was called “Nehru’s Nemesis”. Barrister Nath Pai (1922-1971), elected from the Rajapur Lok Sabha seat on the Praja Socialist Party (PSP) ticket, was a remarkable orator whose research-backed speeches (undocumented in video form) shook PM Nehru. Despite being on the opposite side of Pai’s electoral politics, Nehru not just heard the former’s dissenting voice on the floor of the House, but sought Pai’s company.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Democracy does not function only on the majority of numbers, but on the maximum good of the maximum number...” were Pai’s resounding words that attracted Nehru’s attention to the young critic of his policy imperatives. The friendship between the two yesteryear statesmen, who collided in the Parliament over governance and Centre-state dynamic, reveals their common abiding belief in a democratic healthy discourse. A celebration of this discourse, between two tall leaders of varying ages, ideologies and backgrounds, lies at the core of Aditi Pai’s book Nath Pai, available in English and Marathi.

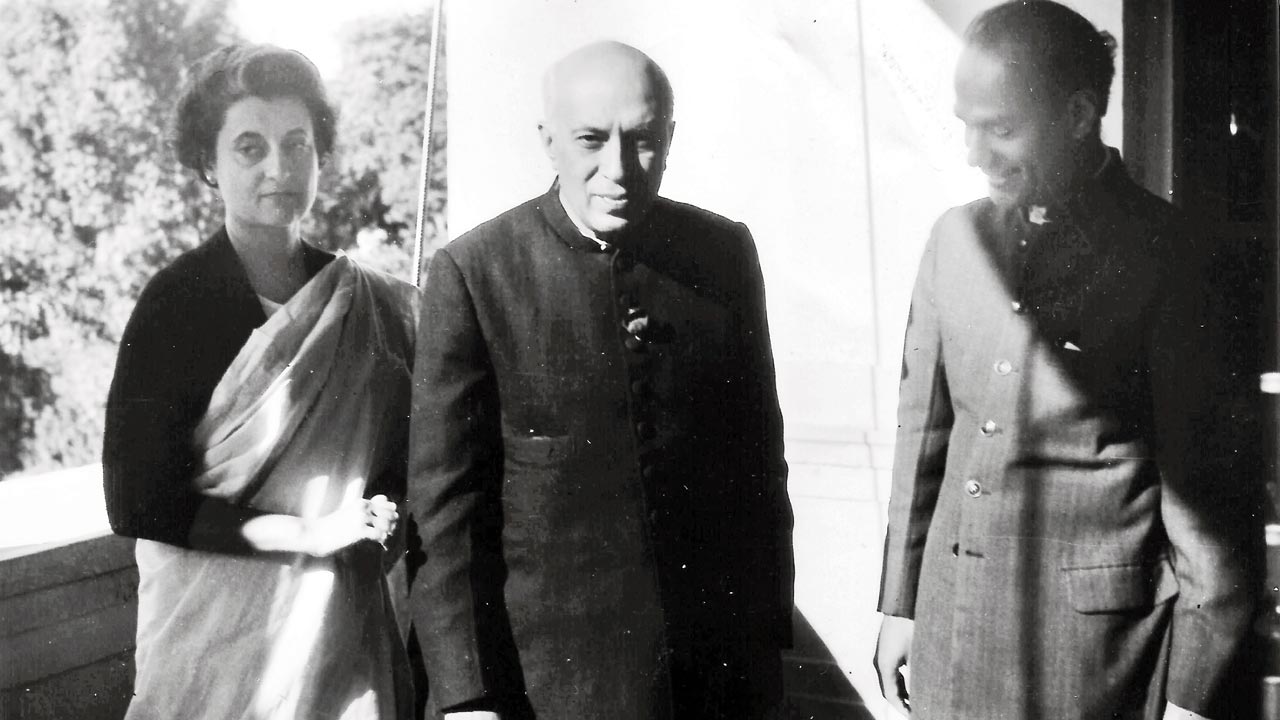

Pai and PM Nehru seen in a public event in Mumbai in 1961. Both the statesmen nurtured a warm cordial relationship, though they often collided in the Parliament. While we celebrate PM Nehru’s birth anniversary today, few would know that it coincides with Barrister Pai’s birth centenary year

Pai and PM Nehru seen in a public event in Mumbai in 1961. Both the statesmen nurtured a warm cordial relationship, though they often collided in the Parliament. While we celebrate PM Nehru’s birth anniversary today, few would know that it coincides with Barrister Pai’s birth centenary year

As soon as I dived into the biography (Rs 320, 181 pages), the protagonist’s first term (1957) as MP captured my imagination. I was instantly reminded of veteran journalist Ashok Jain, whose exhaustive Parliament coverage in the 1980s culminated in a book. He coined the term Mouni Khasdaar/Saansad (Silent MP) for elected representatives, who never spoke a word on their electorate. As part of my reportage of Maharashtra state assembly/council sessions in the ’90s, I knew many delinquent MLAs who resembled inattentive backbenchers. I have met MLAs who regularly took Saturday offs, even in a short three-week session, further under-utilising their constitutionally-granted facility to represent people.

Against the backdrop of shortcut-seekers and shirkers, Pai’s sense of responsibility for his voters is exemplary. In three consecutive terms—he died while campaigning for the fourth in 1971—he raised macro and micro issues to serve Konkan’s interests. In May 1961, he stood on debris-filled roads clearing the fallen trees. His physical presence in the cyclone energised the PSP volunteers. Using his personal connect with PM Nehru and CM Yashwantrao Chavan, he succeeded in getting relief for the remotest hamlets. In Mumbai, he formed the Konkan Vikas Parishad—an apolitical platform, which worked towards the Hirve Konkan Nandanvan goal. As early as 1959, Pai spelt out the need for development funds for a highway, railway and steam boat services, so as to establish connectivity with Mumbai. He urged for electricity generation from the Koyna Dam, and subsidy to local cashew farming and fishing industries, so that the youth from Konkan don’t flock to Mumbai in search of employment.

Pai with PM Nehru and Indira Gandhi at the latter’s residence in New Delhi

Pai with PM Nehru and Indira Gandhi at the latter’s residence in New Delhi

What is striking about Pai is that he was a fierce Konkan putra, with family roots in Vengurla, but he wasn’t limited to his constituency. The Opposition and the Congress party listened attentively to his August 1961 speech on Pakistan President General Ayub Khan’s Hate India hymn and growing proximity with China. The General had called the Indian leadership irresponsible and childish. Pai said Khan had no business to mock the Indian government, as the leaders are the choice of the people of India, irrespective of political differences. “...had it not been for the struggle led by Indian leaders, General Khan would have been a Brigadier clicking his heels before some British commander,” Pai thundered.

But the same Pai was harsh in his criticism of PM Nehru’s denouncement of the Central Government Employees’ strike in July 1960. The PM had launched a scathing attack on the young leaders—Pai specifically—of the strike who were “trying to ride a tiger when they cannot ride a donkey”. Pai’s rebuttal generated laughter in the House, “It is not an offence to be young; maturity and mere grey hair do not necessarily go together.” Later, he asked the PM if two different Nehrus reside in him—the idealist of 1926, who was moved to tears by the plight of the British working class or the PM of 1960, unmoved by the tearful appeals of his own employees.

Pai’s friends from the literati, including PL Deshpande and Acharya Atre (centre). Many of them contributed their personal savings to resuscitate the PSP

Pai’s friends from the literati, including PL Deshpande and Acharya Atre (centre). Many of them contributed their personal savings to resuscitate the PSP

Pai, the first president of the International Union of Socialist Youth, spoke from the heart for varied causes. He voiced the demand for the liberation of Goa before an international audience, so as to shake the Portuguese. He was equally forceful in the demand for the formation of Samyukta Maharashtra or against the atrocities on Belgaum’s Marathi speakers.

Aditi Pai’s book awakens us to a persuasive oratory, which was inner-driven, and that which relied on rich sources like the Upanishads, Vedas and oral folk traditions. Pai would sit for hours in the Parliament library to do his homework. In any given argument, Pai quoted a variety of voices—John Keats, VD Savarkar, Saint Dyaneshwar and senator J William Fulbright—to elucidate his point. His erudition, firm grasp on Constitutional Law and Western world exposure did not distance himself from his people. Instead, his observations had an endearing quality. It’s also crucial to note that he was a polyglot, who not just spoke four Indian languages, but was well versed in German and French. He was blessed with an innate ear for literary wordplay. His reception of the performing arts was also commendable. In fact, the Marathi translation of Pai’s book has greater details of Nath Pai’s friends from the literati—PL Deshpande, Madhu Mangesh Karnik and Mangesh Padgaonkar—who contributed their personal savings to resuscitate the PSP.

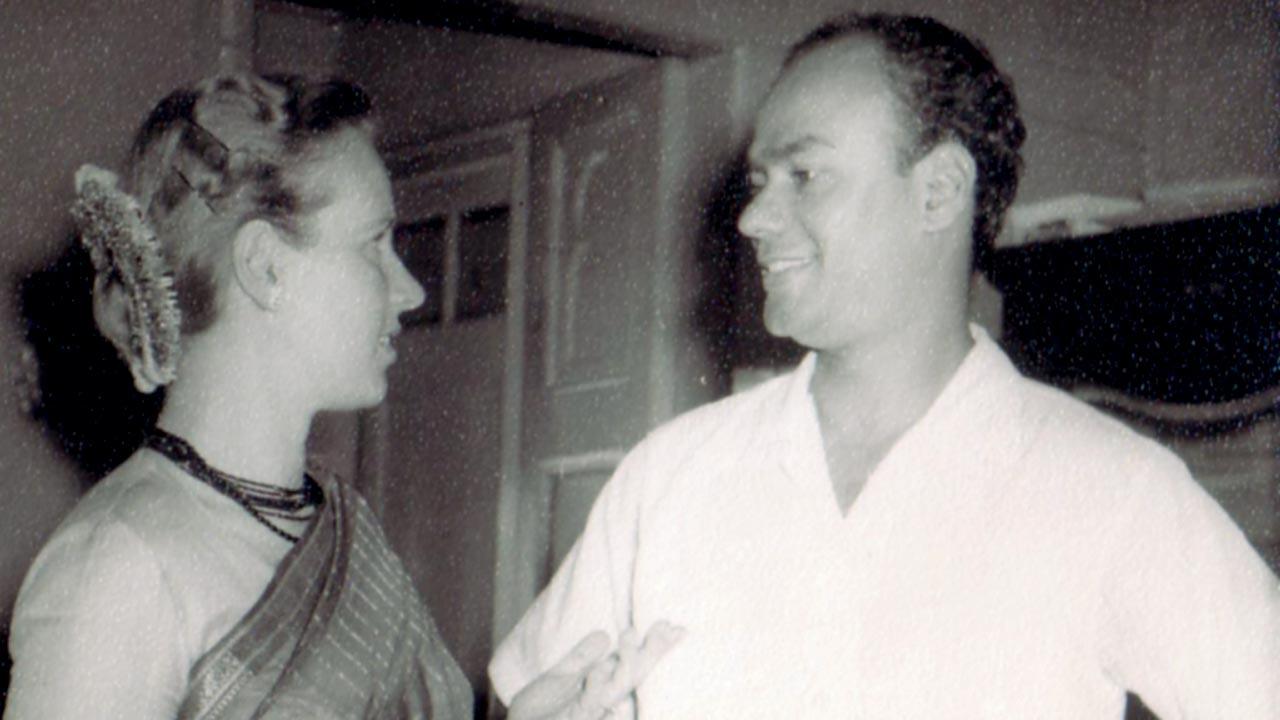

The MP with his Austrian wife

The MP with his Austrian wife

This columnist would have liked if Aditi Pai had elaborated on the leader’s contemporaries in the party. Her book only has passing mentions of a few PSP leaders. But the PSP experiment, however shortlived, does not come alive. The Nath Pai story is about a robust intellectual leadership, which flourished in a certain era in Maharashtra. A marked cadre of samajwadis served in consciously supportive roles, which helped leaders like Pai. This context needs to be articulated for the general education of political outfits in current-day Maharashtra.

The book documents a crucial figure in modern Indian history. It is also written by a journalist, Pai’s grandniece. The author’s father Shailendra Pai is the publisher, who has also brought out its Marathi translation by Anant Ghotgalkar. The Pais approached several mainstream publishing houses to do justice to the life of an extraordinary elected representative, who dreamt of a unified Maharashtra. But as the name Nath Pai did not ring a bell, the family launched the English version, followed by the Marathi in January 2021. Both versions have gone unnoticed, despite a foreword by Nationalist Congress Party chief Sharad Pawar.

Isn’t it ironical that a book, which aims to highlight a forgotten leader of the masses, doesn’t reach beyond a family-friend circle? Hopefully, Aditi Pai’s upcoming compilation of Pai’s Lok Sabha speeches will resonate with contemporary readers, and also present a primer for the new members of India’s Parliament and state legislatures.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!