No prevention and no cure

Updated On: 06 July, 2024 06:57 AM IST | Mumbai | Lindsay Pereira

The state government acts only after something horrible has gone wrong, because we have allowed it to take us for granted

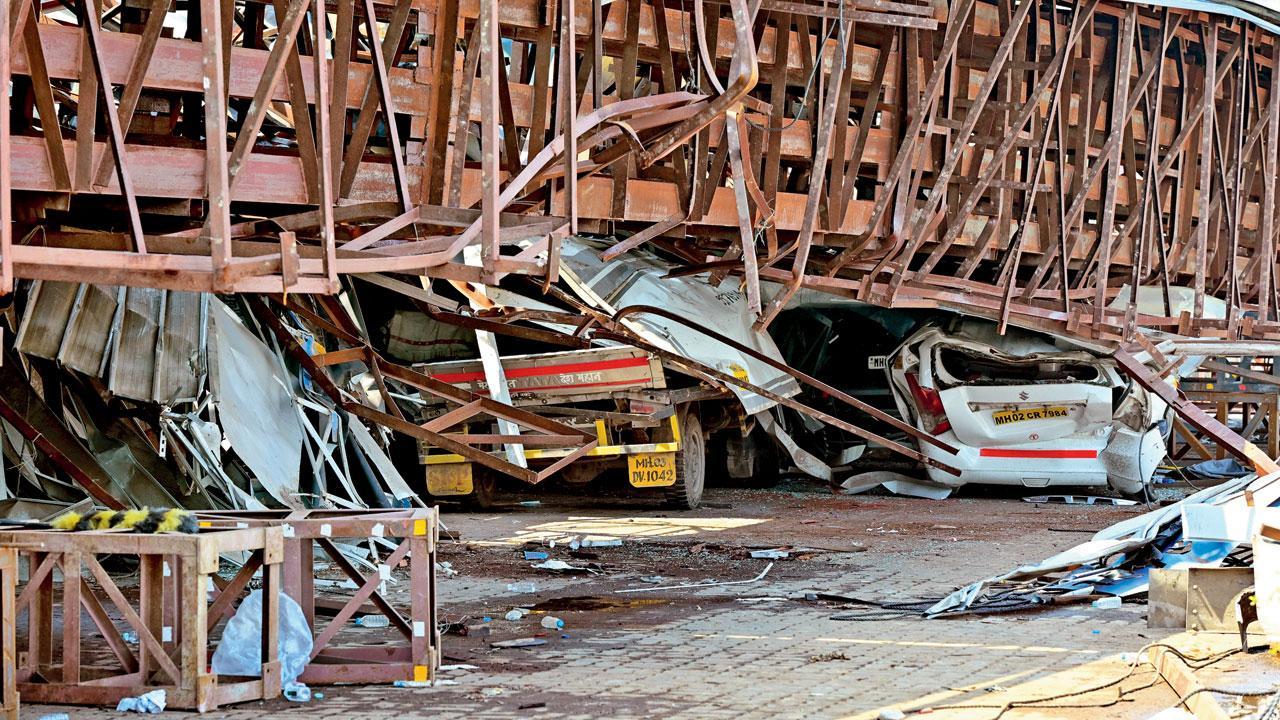

It was only after people died in the Ghatkopar hoarding collapse that a series of discrepancies were revealed. File Pic/Shadab Khan

In May this year, a pub in Pune was sealed a few days after it served alcohol to a 17-year-old and his friends. This wouldn’t have happened if the drunk teenager in question had managed to get home but, unfortunately for him, his sportscar rammed into a bike carrying two people, both of whom were killed. Someone had to be held responsible, obviously, and since the teen was first let off with the harsh punishment of writing a 300-word essay, it only made sense for the pub to be shut down. There was public outrage to be managed, and it’s not as if any police official was going to take the fall.

In May this year, a pub in Pune was sealed a few days after it served alcohol to a 17-year-old and his friends. This wouldn’t have happened if the drunk teenager in question had managed to get home but, unfortunately for him, his sportscar rammed into a bike carrying two people, both of whom were killed. Someone had to be held responsible, obviously, and since the teen was first let off with the harsh punishment of writing a 300-word essay, it only made sense for the pub to be shut down. There was public outrage to be managed, and it’s not as if any police official was going to take the fall.

This isn’t to say there should be no action for serving alcohol to the underaged, only that it says a lot about how there always appear to be two justice systems running parallel to each other in this country. If you’re rich, you can promptly get away with murder. If you’re not, you may have to pay a price disproportionate to your crime. In some instances, you may even find yourself in jail with no charges at all.