A new book by Captain Ramesh Babu resurrects “my own village”—the dockside district of Mazagon—with possibly the widest ranging communities and cultures to grace Bombay

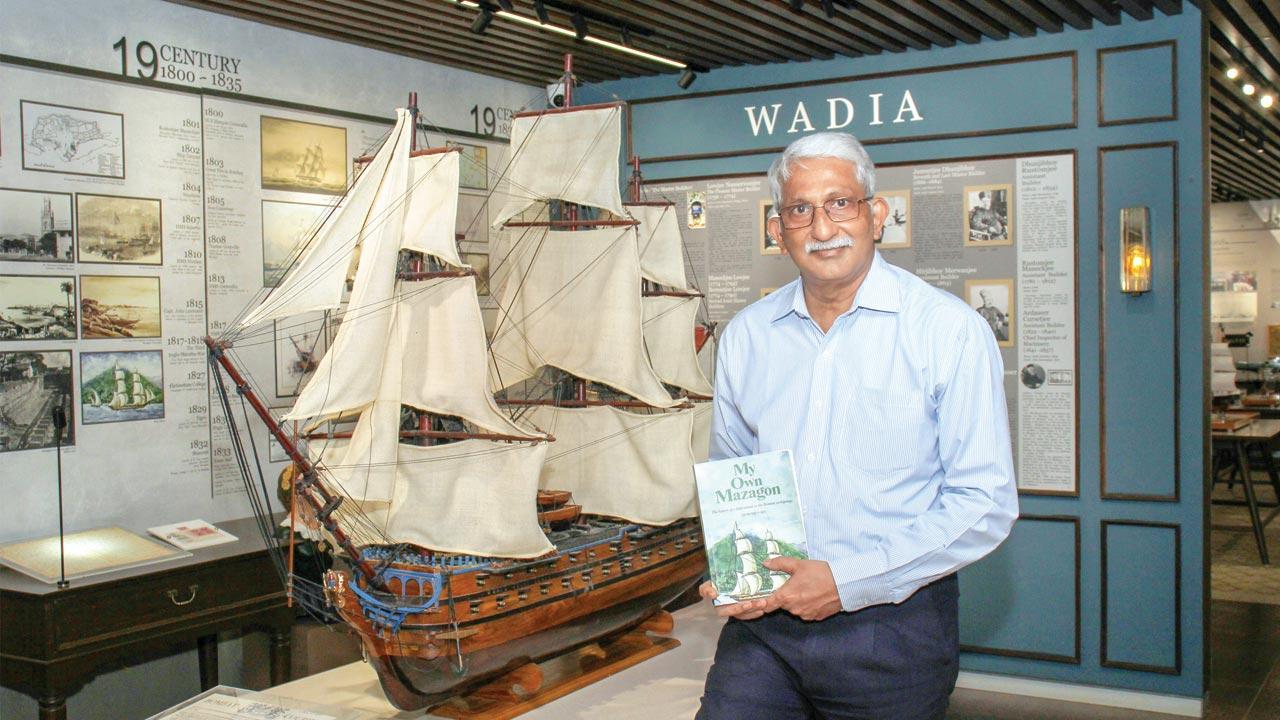

Captain Ramesh Babu with his book, My Own Mazagon, in the Heritage Gallery of Mazagon Dock

We picked up Tristram Shandy, the fictional autobiography, as a compulsory English Lit text, without a clue about its author’s exciting local liaison. Now we know better. Laurence Sterne’s love story-turned-ghost tale is retold with considerable élan by Captain Ramesh Babu in My Own Mazagon: The history of a little island in the Bombay archipelago.

ADVERTISEMENT

Having served in the Indian Navy—as chief engineer of INS Mumbai and first Captain Superintendent of the ship repair yard at Karwar—and Mazagon Dock for 25 years, he documents evolutionary centuries of this harbour hub in progressively illuminating chapters. They flow in an easy, unhurried style, offering a fair amount of information, which will prove less known to several readers. The book is his parting gift to the city he loves, before retirement to the Kerala village, where he spent a childhood hearing his grandmother’s stories of Travancore kings and queens, Calicut Zamorins, Kochi Rajas, Rajputs and Marathas.

Recreation by Rizma Feros of William Hooker’s painting, The Mazagon Mango of Bombay with the Papilio Bolina or Purple-eyed Butterfly

The marine engineer rediscovered the history buff in him at this historic naval dockyard. He has assisted in the conservation of the Ballard Bandar Gate, a look-alike of the Gateway of India, both designed by George Wittet. Mazagon Dock engaged him in 2010 to record its story, spanning over two centuries from 1774. Seven years later, he wrote a book marking the 200th anniversary of HMS Trincomalee. The Bombay-built Royal Navy vessel, Britain’s oldest warship, still berthed at Hartlepool, is a museum ship today.

After these two privately circulated publications, his Calicut Heritage Trails vitally traced the trajectory of monarchs, traders, merchants, sail ships, monsoon winds, invaders, colonisers and a wide milieu of heritage structures, which resulted in converting the thorny marshlands of Calicut to a world-class port.

Including some useful maps and sketches, My Own Mazagon rivetingly resurrects this forgotten mid-town district, once an island with quite a unique identity. Then inhabited largely by Kolis, Bhandaris and Agris, it remained of great significance under the Portuguese, earning them the highest revenue from among all the islands of Bombay. Falling to the Brits, Mazagon retained its geographical identity for two further centuries, with its dock, fort, churches and even a gunpowder factory. Like the archipelago’s other islands, it too found itself merge with the Bombay mainland.

Earlier a prestigious address with beautiful bungalows ringed by luxuriant gardens and sweet-water wells, Mazagon, along with Byculla, gradually waned in importance as an elite preserve, with Malabar Hill and other more southerly vicinities developing. That opened up Mazagon as the vital proletarian part of town, teeming with East Indians, Bohras, Sunnis, Shias, Sindhis, Marwaris, Parsis, Jains and South Indians. They continued residing here in conjunction with the Chinese, Anglo Indians, Armenians and Bahais.

The Chinese Temple, said to be the only still standing shrine of its kind in Western India. Pics/Suresh Karkera

Mapping brief, but brilliant romantic dalliances, the lively exploits of colourful characters and tremendous reach of charismatic institutions, the book is a treat for fans of this fascinating eastern coastline settlement. One which has contributed rewardingly to the mainland it is attached to, yet retained a bravely distinct identity, true to the proud epithet “my village”—Mazagon.

The author responds to excerpted lines, sharing what drew him to rather unusual vignettes in the narrative.

“The Mazagon mango was the reigning emperor of Indian fruits. It was the fleshiest and sweetest, serving the palate of Mughal royals, including Shah Jehan. Let’s hope to discover the lost mango orchard as we go exploring Mazagon.”

Maruti Namdeo Desai (right) represents the third generation at Mankeshwar Hindu Bakery

I chanced upon the Mazagon mango while editing the coffee table book for Mazagon Dock. I only mentioned it, as that was mainly about the history of ships built there. But the mango lingered in my mind. Though I found a tree flowering twice yearly, its fruits were no match to the majestic mango that had tickled the taste buds of Mughal emperors and British governors. My search continued revealing more Mazagon structures and stories, though the mango itself stayed elusive. That stirred me to crave more knowledge about the island. Over the years, I gathered enough material on it. So, in a way, the Mazagon mango inspired me to write this book.

“Every morning, people living along the Mazagon waterfront wake to the Muezzin’s call from Nawab Ayaz mosque. Nawab Ayaz is perhaps the most interesting character in the history of Mazagon. But he has been forgotten by chroniclers.”

A historic 226-year-old grave inside Rosary Church on P D’Mello Road, Wadi Bunder

The Nawab had been a character of much intrigue, ever since I realised people had no clue of him, though a mosque, a tank and a road bear his name. With no trace of him left, except the name, it was tough tracking him down. I spent weeks scouting for clues, finding Nawabs from Arcot to Awadh. The one from Mazagon was missing.

Suddenly, one day, I found a 19th-century panorama of the Bombay Harbour, with Hyat Sahib’s house marked. That took me back to the 1879 Malabar Manual of William Logan, which I’d earlier referred to for my book, Calicut Heritage Trails. Hyat is featured in this manual as a Nair boy, who became Muhammad Ayaz and later a Nawab, traversing a patchy path from Malabar to Mazagon. Linked references to records of the Anglo-Mysore War and a 2008 blog indeed established him as the Nawab of Mazagon I looked for. Finally, I could create a chapter unveiling the story of the Nawab, who may be lying buried under the Nawab Ayaz Mosque.

“Belvedere House was the scene of the most romantic story of Mazagon, barely mentioned by Indian historians in accounts on British Bombay. It was the residence of Eliza Draper… haunted for years by her spirit, ‘flitting about in the corridor or verandah in hoop and farthingale’.”

Torn between her “detestable conjugal life” with an East India Company official of “formal manner and illiterate tastes”, and her hopeless love for a man of letters, who wore a pendant with her picture, Eliza Draper eloped from her house with a view on the hilltop, which also guided ships arriving at Mazagon from Europe.

The episode caused a sensation in colonial social circles. Romance and pathos, mixed with British boarding school poise and a bit of adventure sum up the character of Eliza. She adds a tinge of mystery to the story of many a British Memsahib, who silently suffered on the sidelines of a colonial power. I had a clear view of whatever is left now of the Mazagon hill from my dock balcony as I wrote. So, I literally felt Eliza’s anxieties and apprehensions. As a mariner, I also identified with the frigate captain helping her escape a miserable life atop Mazagon hill. My account of Mazagon would have stayed incomplete without Eliza Draper’s tragic saga.

“Over the years, Mazagon’s very own pav, bread and biscuits have breached the limited boundaries of the long-lost island to spread their fragrance worldwide.”

Fragrance of food is such an essential part of any heritage enthusiast’s explorations, especially in a locality accommodating multiple cultures. Walk the streets of Mazagon and what overwhelms you is the fragrance of baked wheat from its many bakeries. These have been around for long years, serving the working-class populace that made a living as dock workers, mill hands and low-paid labourers. Each carries the imprint of generations of bakers of different communities. Starting with Mankeshwar Hindu Bakery near the waterfront, to Roshan and Philomena bakeries. Mankeshwar charmingly bakes what customers bring in trays, in their oven, which is fired and on round the clock.

Wibs, the iconic bread baker, Britannia the biscuit maker and a few struggling old bakeries are losing traditional customers to the rapidly changing demography of Mazagon. Their aroma, which I inhaled during morning walks, was so compelling that I just had to dedicate an entire section to pav, bread and biscuits.

“The Mazagon Chinese temple was once the sought-after place for prayers… Notes of Mandarin and Cantonese music may soon die here. But Mazagon will continue to resonate with the harmonious symphony of church bells, muezzins’ cries and conch calls, inviting believers to its many places of worship.”

Local historians so far hold that the Chinese made their presence in Mazagon as dock workers, only in the early part of the 20th century. That is based on the date of construction of the Chinese temple (1919), worshipped by a few Chinese families like those of Mr Liao and Mr Wenkong, who still live here. But from old newspaper reports I discovered that the Chinese were here almost 40 years before, building ships at the docks.

Growing in numbers to set up an entire Chinese colony, very close to the docks, they made a definite contribution to Mazagon’s history. Apartments near the temple saw a vibrant Chinese colony living in harmony with Kolis, East Indians, Pathans, Parsis and other communities. Sadly, most of the Chinese have gone, leaving only a few families and still revered idols at their temple. Empty homes around stand as silent sentinels of a culture the precinct seems to have lost forever. One wonders what will come of these homes and the Chinese temple, as and the dwindling community goes extinct with time.

Only for mid-day readers

Buy a discounted copy of My Own Mazagon on indussource.com, using the coupon code MazagonMD

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at meher.marfatia@mid-day.com/www.meher marfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!