The moon of confusion

Updated On: 31 October, 2021 07:24 AM IST | Mumbai | Paromita Vohra

Had tradition gamed technology, or had technology questioned tradition? Oh the moon of confusion, it casts a wondrous light

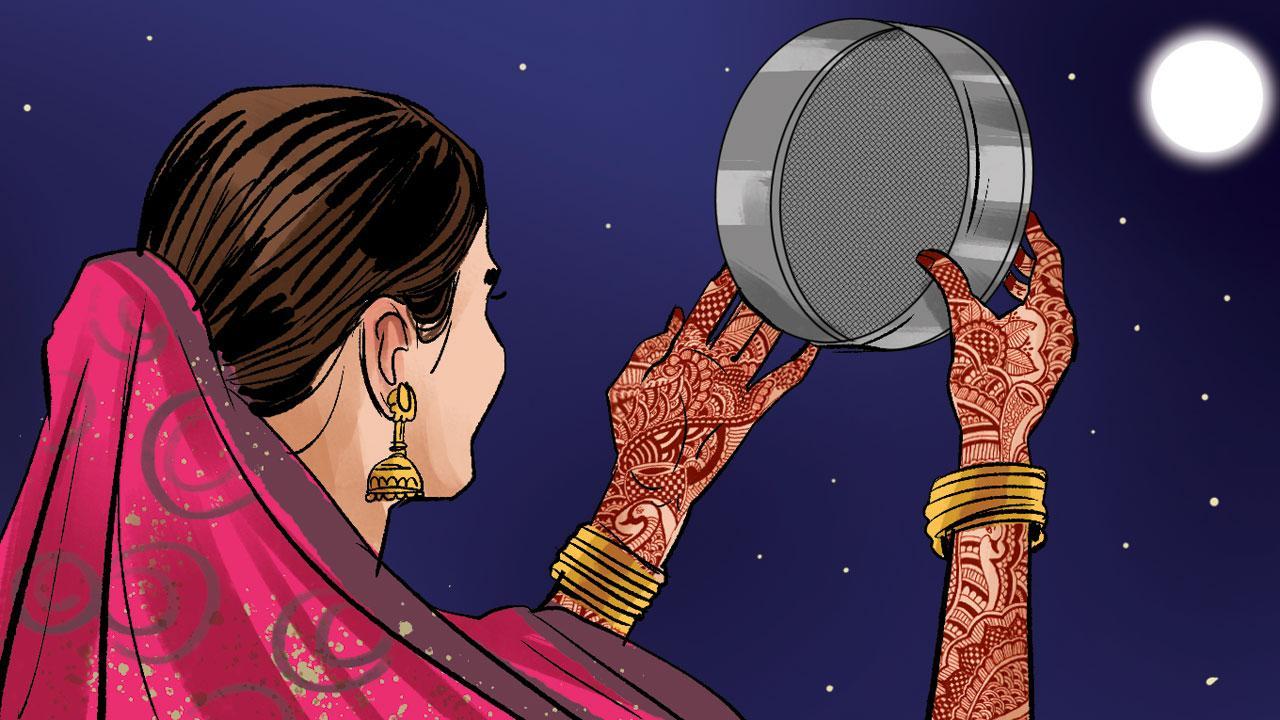

Illustration/Uday Mohite

![]() My friend, a teacher, received an email from her school with the subject line: biometric error due to henna. Employees punching in and out with hands covered in Karwa Chauth mehendi were confusing the scanners. Had tradition gamed technology, or had technology questioned tradition? Oh the moon of confusion, it casts a wondrous light.

My friend, a teacher, received an email from her school with the subject line: biometric error due to henna. Employees punching in and out with hands covered in Karwa Chauth mehendi were confusing the scanners. Had tradition gamed technology, or had technology questioned tradition? Oh the moon of confusion, it casts a wondrous light.

Little such confusion was to be obtained in online debate. Along with the ritual of fasting for Karwa Chauth, is the parallel digital ritual of objecting to Karwa Chauth. This debate keeps marriage centralised but also obscures a confusion in categories—not every married person wants to be married, and not every single woman wants to be unmarried. There may be hazaron khwaishein in the worlds, but in public debate, there are usually only two positions, kind of like in marriage.