Ghashiram Kotwal, the iconic Indian play which enters its 50th year, teaches us to embrace inglorious chapters of history without getting too sentimental

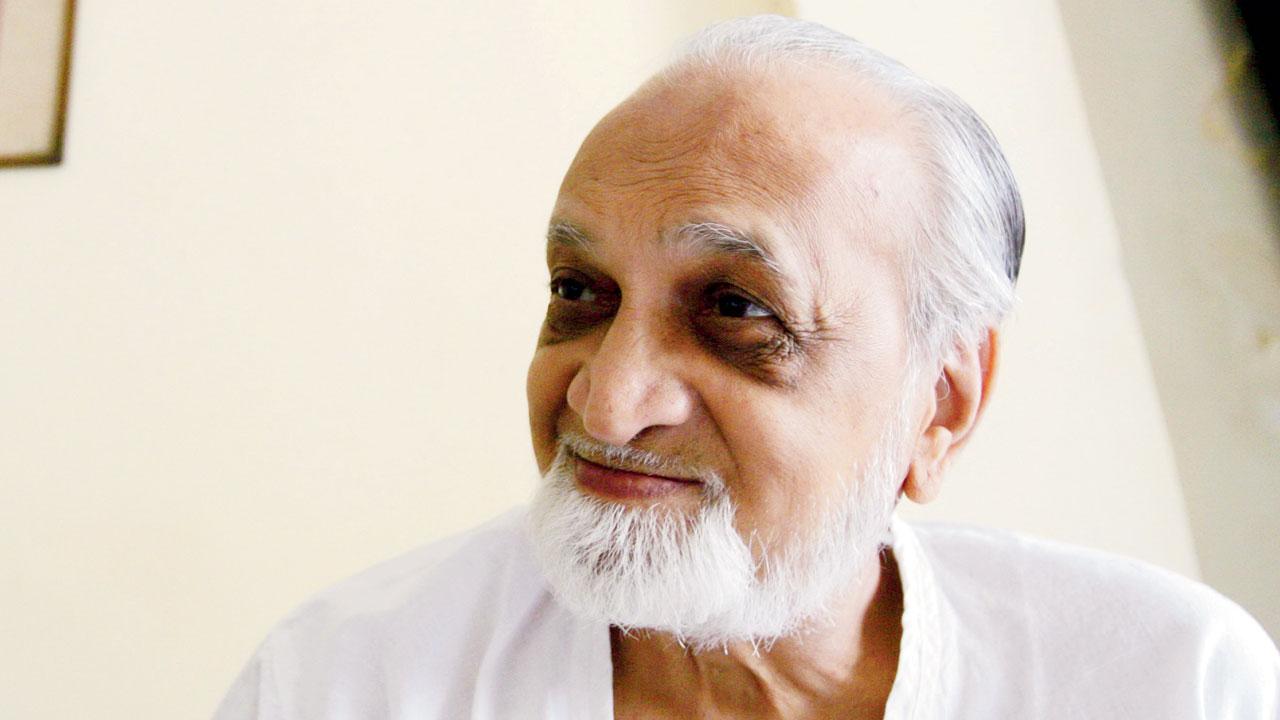

Pic/Satej Shinde

Image caption: Theatre critic Deepak Ghare, 70, was approached to write Ghashiram Ek Vaadal long after Theatre Academy suspended production of Ghashiram Kotwal. Publishing house Granthali felt the need to archive the stormy journey of the unconventional musical.

ADVERTISEMENT

![]() As per history, Nana Phadnavis was the chief minister of the Peshwas from 1773 to 1800—whose astute political strategy and statesmanship kept the Maratha empire free from British aggression.” The glowing testimonial was religiously read aloud by director Jabbar Patel before each performance of Ghashiram Kotwal, the Vijay Tendulkar-written Marathi play, when it travelled to Europe and Britain in the teeth of intense political opposition from certain sections in Maharashtra. That was way back in September 1980. Patel preceded the shows with a rider, duly translated in respective European languages, so that the foreign audience (German, French, Dutch) was saved from forming a negative and scandalous image of the historical character Nana Phadnavis, whose fictional avatar was the premise of the play.

As per history, Nana Phadnavis was the chief minister of the Peshwas from 1773 to 1800—whose astute political strategy and statesmanship kept the Maratha empire free from British aggression.” The glowing testimonial was religiously read aloud by director Jabbar Patel before each performance of Ghashiram Kotwal, the Vijay Tendulkar-written Marathi play, when it travelled to Europe and Britain in the teeth of intense political opposition from certain sections in Maharashtra. That was way back in September 1980. Patel preceded the shows with a rider, duly translated in respective European languages, so that the foreign audience (German, French, Dutch) was saved from forming a negative and scandalous image of the historical character Nana Phadnavis, whose fictional avatar was the premise of the play.

Theatre Academy’s 40-strong performing troupe was thus, notified by the Bombay High Court to exercise care and caution, while representing an Indian story abroad.

This event is the defining climax of the book Ghashiram Ek Vaadal, a captivating blow-by-blow account of the cyclonic journey of the modern classic. It is penned by Deepak Ghare, 70, theatre critic, design artist and one of the editors of the Encyclopaedia of Visual Art of Maharashtra. The slim 150-page memoir evokes a suspense that pure documentation or mere popular narrative wouldn’t have ever achieved. In a quiet meditative and yet-tantalisingly pacy style, Ghare recaps the events leading up to the hush-hush Berlin flight of Theatre Academy actors, who had to smuggle themselves to the Mumbai airport post midnight hours in a manner befitting the handover of extradited convicts.

The book celebrates the cast, its director, donors, and family members, who pursued their freedom to perform and endorse a play, which was labelled anti-national, objectionable and obscene.

Ghashiram Kotwal was Vijay Tendulkar’s third play to attract extreme public reactions. The play was allowed to go abroad by PM Indira Gandhi only because it was profusely praised by filmmaker Satyajit Ray. Pic/Getty Images

Ghashiram Kotwal was Vijay Tendulkar’s third play to attract extreme public reactions. The play was allowed to go abroad by PM Indira Gandhi only because it was profusely praised by filmmaker Satyajit Ray. Pic/Getty Images

Ghashiram Ek Vaadal, which recalls the violent protests of the culture police in Pune and elsewhere, has been this columnist’s go-to read for gloomy days, as well as upbeat ones like the upcoming World Theatre Day (March 27), dedicated to celebration of the potency of theatre to change life. It is one Marathi book that deserves a wider audience, by way of an English translation, especially considering that only a handful of contemporary Indian plays have earned international recognition.

Ghashiram Kotwal will turn 50 this year, if one were to factor in the first December 16, 1972 performance mounted by the Pune-based Progressive Dramatic Association. The famed production of the play, however, is credited to the Theatre Academy, a fledgling group which broke off from PDA in 1973 and performed the play with courage and swagger till 1991. Nana Phadnavis played by Mohan Agashe, now 74, in this production is an electrifying role that is recalled till date as a record in Indian thespian history. The feat was later attempted by a lesser known Trimiti group. Ghashiram was revived in 1994 under the stewardship of actor Madhav Abhyankar who continues to play Phadnavis in over 1,200 shows. Needless to add, Abhyankar’s Nana has always been judged on a relative scale. “For me, the joy is in keeping a milestone relevant. I don’t mind braving the comparison.”

Ghare’s book was written in 1996, when Theatre Academy had long suspended the production. Publishing house Granthali, one of the support groups of Ghashiram since the 1970s, felt the need to archive the stormy journey of an unconventional musical, which embraced Maharashtra’s folk elements with élan. The play alluded to the modern-day power equations; it was Indian to the core and yet not heaving with regional pride. On the contrary, it used a popular myth to question the ruling class. Ghashiram was a power-packed visual-aural-intellectual combo like none other.

Knowing Ghare’s credentials and domain knowledge of the performing arts, Granthali founder Dinkar Gangal entrusted him with the research required for the documentation. For over three years, Ghare interviewed the playwright, director, cast, backstage crew, music director and opponents, before setting out to write the “thriller”. He prefaced Ghashiram’s history with three layers—first, playwright Tendulkar’s political makeup in pre-Emergency Maharashtra; second, the reformist pro-people politics of 19th century writer Moroba Kanhoba whose original novel on a real-life Ghashiram inspired Tendulkar; third, the impact of the Peshwa rule on the Marathi mind. Ghare has also traced the Marathi psyche in the context of the moral-religious lens used for art appreciation.

Ghare’s interviewees were multi-hued and polarised. He had to deal with extreme haters of Vijay Tendulkar (1928-2008) and diehard fans of every word he wrote. Also, talking to a soft-spoken Tendulkar was a task in itself. Even after the book was out, and much-appreciated in Mumbai’s theatre circles, Ghare didn’t get any reaction from Tendulkar. “He wasn’t particularly articulate when I visited his residence, but his wife definitely appreciated the spirit behind Ghashiram Ek Vaadal. She openly said that the book painstakingly recounts the fear and tensions experienced by the Tendulkars and other families [of theatre actors] who were made to feel guilty for owning up a seemingly political script.”

Ghashiram Kotwal—after Gidhade and Sakharam Binder—was the third Tendulkar play that attracted extreme public reactions. The playwright was targeted for his explosive anti-establishment language and visceral treatment of taboo subjects like sex trade. In fact, another book, Binderche Diwas, encapsulates the price paid by director Kamalakar Sarang and Tendulkar for defending a script in public realm and also in the court. The play, temporarily banned in 1974, was labelled an immoral story of a small-time bookbinder who chooses destitute women as sexual partners, but keeps them free from wedlock.

Ghare’s book goes close to Binderche Diwas in its texture, though it is not written by a practitioner. It gains because of the author’s emotional distance, while imbuing it with the warmth of a first-person witness of turbulent political-cultural phases in Maharashtra. The book’s second edition (2005) came after the formation of the Nationalist Congress Party and a little before the birth of the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena, which has further added to Maharashtra’s fractious political fabric. Numerous parties and factions have created new lobbies and cultural watchdogs in the state. A play’s content (or that of any work of art) now runs a greater risk of hurting the sentiments or interests of one segment or the other.

Interestingly, Ghashiram Kotwal’s shows were recently hosted by BJP MP Udayanraje Bhosale, 13th descendant of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, in Pune and Satara. The audience reportedly enjoyed the Kotwal’s scheming and Nana Phadnavis’ diplomatic moves. One wonders what this reception means—are we to conclude that a sharp play on caste politics is nothing, but evening entertainment in 2022 Maharashtra? Or, is it that a veiled satire is perceived harmless by the political class?

To me, Ghashiram Ek Vaadal is an expose. It bares the duplicity of theatre people, institutions, social groups, politicians, administrators, lawyers who objected to a playwright’s take on a mythical tyrannical Kotwal who, at one point in history, abused power and who in turn was used (and thrown) by his political master. The book names known people, some of them no longer alive, who said mean regrettable things against fellow theatre practitioners. It wasn’t just the Shiv Sena or conservative groups (Lingvaad Nirmoolan Samiti), which opposed the play, but ministers in the Congress party also felt that the Ghashiram chapter was best avoided and certainly not worth a display in front of foreigners. The play was allowed to go abroad by PM Indira Gandhi only because it was profusely praised by filmmaker Satyajit Ray.

Tendulkar repeatedly stated that he hadn’t written a historical play; he later apologised for the unintentional hurt caused to Puneri Brahmins. Ghare holds this against the playwright. Ghare feels Tendulkar’s refrain was a bit overdone. He could have stood by his choice of subject in a “so-what” stance. The Marathi self-image was shaken by Tendulkar’s thematic choice, which compelled people to apply other-than-artistic parameters in their appreciation of the story.

Ghare sees a minor silver lining in this episode—Ghashiram gave an opportunity to people to assess their own thoughts on life and art. It coaxed them to see which side of the spectrum they belonged to. Few Indian plays can boast of providing such a moment of reflection.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!