North Bombay and SoBo share an interesting cultural connect, thanks to some visionary philanthropists

Tejpal Hall at Gowalia Tank

Never the twain shall meet… Among Rudyard Kipling’s multiple misquoted lines, this chant from The Ballad of East and West, has the imperialist poet describe far-flung cultures intertwined rather than estranged. Something like the North Bombay-SoBo divide which accuses one vertical end of the city of knowing little about the other. Here’s a quartet of stories with common threads weaving together both, owing to visionaries who cared to bequeath Bombay a collective future.

Never the twain shall meet… Among Rudyard Kipling’s multiple misquoted lines, this chant from The Ballad of East and West, has the imperialist poet describe far-flung cultures intertwined rather than estranged. Something like the North Bombay-SoBo divide which accuses one vertical end of the city of knowing little about the other. Here’s a quartet of stories with common threads weaving together both, owing to visionaries who cared to bequeath Bombay a collective future.

The link isn’t so obvious. Take Colaba and Dadar, for starters. When the former’s road signs announce Pasta Lanes, you can be forgiven for dreaming of la bella Italia’s delectable dish. But these four paths off the Causeway have zip to do with anything Italian. Pasta Lanes 1, 2, 3 and 4 are a decidedly desi throwback to a philanthropic Kutchi Bhatia clan.

ADVERTISEMENT

Vile Parle Station owe their existence to Goculdas Tejpal’s family

Vile Parle Station owe their existence to Goculdas Tejpal’s family

“The name of Sheth Goculdas Liladhur Pasta stands high on the list of those who upheld the fair fame of the City of Bombay,” reads the section on the stalwart in Representative Men of the Bombay Presidency. Studying this rare volume with Pasta’s great-grandson, I learnt that Goculdas’ ancestor, Sheth Mohanjee, reached here around 1855 to trade in cotton—“He won the title of ‘pasta’, or ‘prince’, on account of his generosity, and this cognomen is borne by his descendants.” Honouring the trust that the British invested in them, Goculdas and his son Madhavdas sponsored civic services, temples, dharamshalas, wells and tanks.

It was literally my nose that led me to a pair of similarly christened Pasta lanes, behind Chitra Cinema on Dr Ambedkar Road, Dadar. Caught in a swirl of smells—Phillips Coffee and Kailash Mandir Lassi near the station, tandoori rotis pressed hot on the pavement outside Mohamedi Restaurant (now Zaiqaa)—I stopped at Gupta Soaps factory in Goculdas Pasta Lane. Even behind closed doors, whiffs of sudsy detergent and Hamam soap (a torn ad for which still stuck jagged on the paint-peeled wall) seemed to blow fragrant bubbles at me.

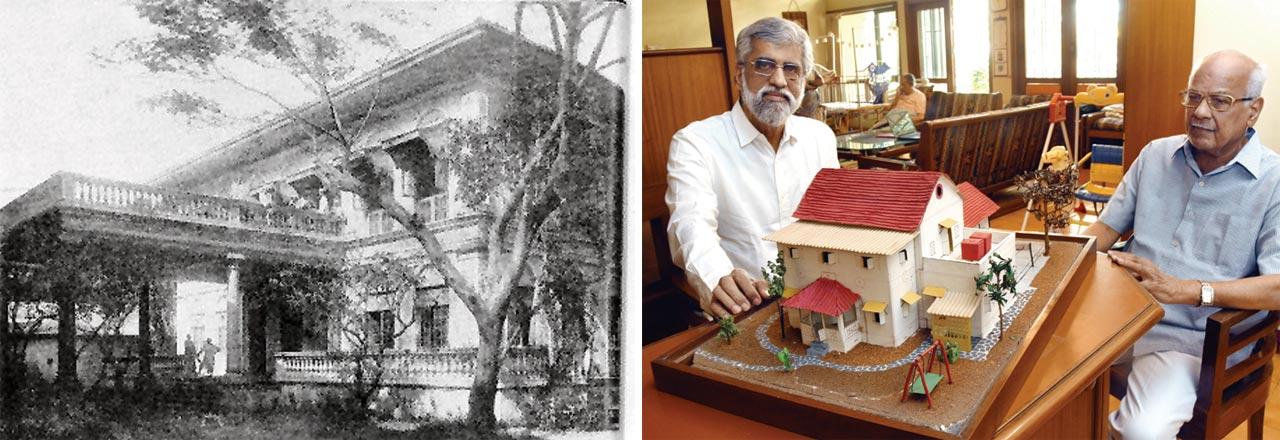

Mor Bungalow in Vile Parle. File pic and Satej Shinde

Mor Bungalow in Vile Parle. File pic and Satej Shinde

Easy to imagine such scents once offset the malodour of heavy-layered greasepaint from Ranjit Studios round the corner, where directors up until Manmohan Desai shot serial blockbusters. In fact, the movie mogul with the Midas touch believed that space was extremely lucky for him.

The location where Manji, as the industry hailed him, filmed Amar Akbar Anthony’s qawwali sequence with Rishi Kapoor booming “Purdah hain purdah”, was Tejpal Hall at Gowalia Tank. Initiated by Radhakumar, the great-grandson of merchant Goculdas Tejpal, from Kothara in Kutch, the 639-seater Sheth Goculdas Tejpal Auditorium opened doors to theatre-loving throngs in September of 1960. Significantly, on December 28, 1885, the Indian National Congress had been formed at the Tejpal Sanskrit College on this stretch of Tejpal Road.

Topiwala National Medical College, whose benefactor was Motiram (Topiwala) Desai; his Goregaon relatives, the Samants, with a model of their 1891 cottage. Pic courtesy/TNMC and File pics

Topiwala National Medical College, whose benefactor was Motiram (Topiwala) Desai; his Goregaon relatives, the Samants, with a model of their 1891 cottage. Pic courtesy/TNMC and File pics

“Our father assigned specialisations to experts like the civil engineer BE Doctor,” said Sudhir Tejpal, Radhakumar’s son. “Actors and audiences have much appreciated our auditorium’s acoustics.” Booked way in advance for diverse programmes, the venue’s fine sound standard drew groups like the Bombay Madrigal Singers Organisation to packed houses at each concert. Opera buffs remember enjoying sopranos like Celia Lobo essay the role of Violetta in a 1962 performance of La Traviata.

Way across town, half a century earlier, with public welfare uppermost in mind, the patriarch’s son, Govardhandas Goculdas Tejpal, donated four acres of land plus a

considerable monetary dispensation to build Vile Parle Station around 1906. The Tejpals also developed a vital network of roads from the early 1920s, referred to as Tejpal Scheme today too.

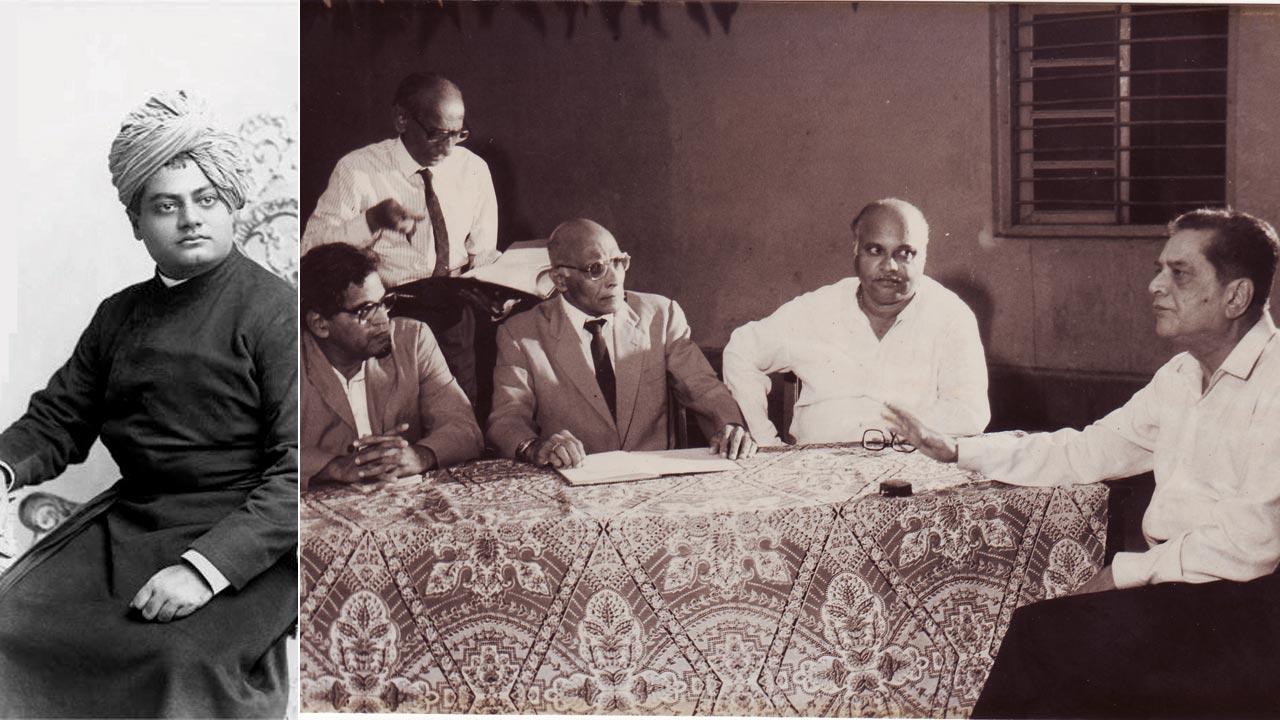

Swami Vivekananda stayed in the Borivli home of Chhabildas Lalubhai; still from Uddhwasta Dharmashala at Chhabildas School, Dadar. Pics Courtesy/Wikimedia Commons and Dr Shreeram Lagoo/Roopvedh Archives

Swami Vivekananda stayed in the Borivli home of Chhabildas Lalubhai; still from Uddhwasta Dharmashala at Chhabildas School, Dadar. Pics Courtesy/Wikimedia Commons and Dr Shreeram Lagoo/Roopvedh Archives

In a display of keen aesthetics, Govardhandas combined entrepreneurial acumen with the pleasure afforded by having designed a grand ancestral seat in Vile Parle, which dazzled citywide. Taking five years to embellish, the four-acre palatial property was crowned by a distinctive brass peacock perched on an impressive dome. Mor Bangla, as it was called, presented striking glass mosaic inlays winking colours in different light and rolling gardens with a swimming pool. After the 1950s, this gem gradually lost its lustre, the splendour replaced by a chaotic municipal market, Agrawal market and the Dinanath Mangeshkar Natyagriha.

Other city institutions that the Tejpals extended their munificence to include the Goculdas Tejpal Hospital and GT School.

Pasta Lane 1, of the quartet of Colaba roads sharing their name with Dadar lanes which honour philanthropist Goculdas Pasta. File pic

Pasta Lane 1, of the quartet of Colaba roads sharing their name with Dadar lanes which honour philanthropist Goculdas Pasta. File pic

Bridging the miles from Bombay Central to Goregaon, education and cinema scored unique goals through the respective charities of the Topiwala and Samant families. Filmmaker Vikas Desai Topiwala tells a riveting tale of his hatmaker great-grandfather Anant Shivaji Desai Topiwala, who ran away at 11 with a mere rupee in his pocket, from Walawal village in Sawantwadi to the 19th-century city.

Apprenticing as a tailor, he progressed to fashion stylish headgear for the creme de la creme and rose to be a rich landowner. His descendants gifted Bombay the Topiwala National Medical College at Bombay Central and Topiwala Theatre in Goregaon.

Besides crafting signature topis, Anant Shivaji Desai dealt in silver, copper and brass kitchen implements. His son Narayanrao continued trading in metals. Narayan’s son Motiram Desai pioneered anodised aluminium in India, as well as introduced velvet fabric. He and his stepbrother Sitaram became empire builders imbued with rare altruistic zeal.

Better known as Topiwala Desai, Motiram made a memorable contribution to fund more expansive facilities for Topiwala National Medical College. In 1946, he nobly signed a blank cheque in 1946, on which Congressman SK Patil famously proceeded to ink: “Rs 5,00,000”.

Guiding me between Goregaon gullies, the soft-spoken Girish Samant, son of freedom fighter Baburao Samant, laughed, “We are the aborigines of Goregaon. Ours was one of only three pucca homes in a tangle of jungle jhopdis. Vikas’ father Motiram held my father in high regard and assigned him responsibilities in family trusts.” Motiram Desai’s mother was Girish’s grandfather Balkrishna’s cousin.

Before it became a multiplex, Topiwala Theatre in Goregaon, with over 1,000 seats, was constructed by Sitaram Desai in 1969, with Asia’s first mirror screen—two screens flashed from one projector.

A sage and a stage connected unusually, as I discovered while working in Borivli. This north-western suburb is soil that Swami Vivekananda trod. A year prior to his journey to America from Bombay in May 1893, representing India at the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago that September, the philosopher happened to be in Bombay. Barrister and Sanskrit scholar Ramdas Chhabildas invited him to stay awhile at Samudra Villa, the long-porched Chhabildas bungalow with stables, off Nepean Sea Road.

Together, they visited Ramdas’ father Chhabildas Lalubhai’s Borivli home. The three men then proceeded to the Kanheri Caves, whose rock-cut architecture inspired Vivekananda to visualise the Ramkrishna temple at Belur Math.

In an essay on Vivekananda’s city hosts, Swami Shuddharupananda has written: “The Borivli bungalow of Chhabildas Lalubhai was where he entertained. It is possible Swamiji was lodged in this. In the evening many people visited to listen to his talks.”

A young man called Chandrakant was among them. With his guru passing, the disciple halted daily by that house, hands humbly folded in salutation. He followed this routine until he died at a ripe age, Sunil Goragandhi, great-grandson of Chhabildas Lalubhai, told me in his busy Borivli cafe on Chandavarkar Road.

Goragandhi’s mother’s grandfather lent his name to Chhabildas High School in Dadar, the crucible of vital 1970s theatre genres, especially Marathi.

“Chhabildas was a place where you could make a fool of yourself, where great creation could happen. It was heaven!” exults Naseeruddin Shah in The Scenes We Made: An Oral History of Experimental Theatre in Mumbai, edited by Shanta Gokhale. “It helped me realise the damn front curtain was an archaic bloody institution.”

Not just a space to put up plays, this cultural crib cradled the most brilliant personalities. Repository of an all-Maharashtra movement galvanising the drama world with dynamic thought, Chhabildas hall served as an equally levelling force within Bombay. Arpana director Sunil Shanbag explains: “If there was something like Shivaji Underground at Bhimnagar Mohalla at Chhabildas, the same slightly ‘SoBo-gentry’ types there at NCPA turned up to see it. You’d have a Shyam Benegal, a Jennifer Kapoor—who would stick out in the audience.”

Boosting business for the small batata vada stall downstairs and chaiwala at the back, Chhabildas proved an embracive meeting point, for practitioners like Sunil Tawade from Borivli or Shafaat Khan from Mumbra.

To cynics writing off that stage renaissance, Rajiv Naik offers a hopeful view in the book—“Every generation looks for its adda, its platform. The golden age is a

myth created by the old. The messiah has never arrived. He is always awaited.”

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at meher.marfatia@mid-day.com/www.meher marfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!