Since a decade, Kareena Gianani has been covertly peeking into a home visible from the JJ flyover. Beyond its window sill are walls displaying Chinese and British-patterned ceramic plates. She finally pops in, and finds a mini museum inside

Nakdevi Street, a lane parallel to Mohammad Ali Road, is a curry of sounds and aromas a few hours before Roza. For the past 30 minutes, I have been walking on the main road, passing by men hawking small hills of dates, my eyes skyward, feet unsure.

ADVERTISEMENT

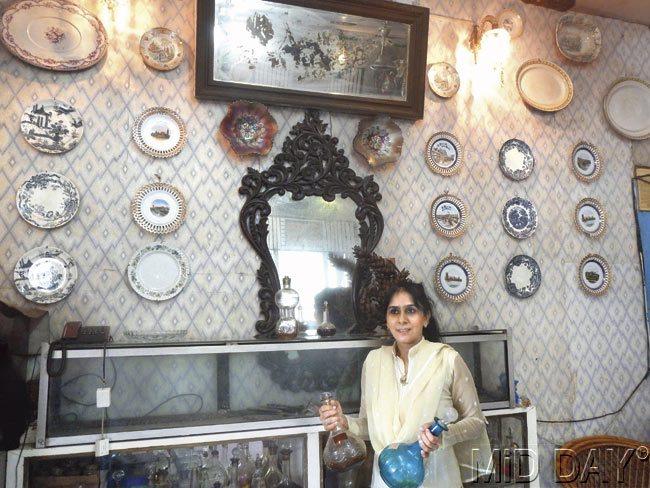

Shaheen Banaraswala is accustomed to Parsis and foreign tourists parking their cars at JJ flyover and shouting across, offering to buy her collection. Pics/Suresh KK

One could say it is divine intervention I seek. Since almost a decade, being on the JJ flyover has involved a curious ritual. Somewhere after Minara Masjid, emerges the view of a window to the right, whose windows are as wide as a glad host’s arms. Beyond them, on the wall, hang 70 ceramic plates.

It is this home I now seek, and, down on the street, finding it is daunting. I seek a three-storeyed building, light pink in colour, and well, that’s all I know. After asking people around for the “platewallah” home, I find it, and walk up the wooden stairs and banister. The building has both homes and offices (Baggo, House of Bags), and, unless my olfactory powers deceive me, there’s a fat-laden feast cooking somewhere.

The plate lady

Shaheen Banaraswala, 40, answers the doorbell and does not find it strange that a stranger wants to look at her collection of plates. The living room is cacophonic with tyres screeching and honks yelping out on the JJ flyover, but Shaheen’s effervescence is unwavering. I step inside, in a time warp.

The plates are there, but what is not visible from the JJ flyover is a wall-to-wall showcase with antique crystal vases, ancient brass goglets with intricate meenakari gold work, and ceramics not found today.

I am resigned to having itchy hands as long as I am here, but my resolve is shaken when Shaheen asks me to take a seat beside an ancient wooden table so impossibly intricate that I can see the expression on the faces of monkeys, deer and the shepherds.

“These two tables and another chest inside were built from the trunk of a single walnut tree in Kashmir,” says Shaheen. I peer at the plates and find Chinese dragons, Chinese tea parties and views of London immortalised on this home’s walls.

It was Shaheen’s father, Haji Mohammad Yusuf Banaraswala, who curated this collection. Haji passed away in 2009 at the age of 104. He traded in Benarasi sarees with gold and silver work, and collected bric-a-brac on his travels and at royal auctions held across India.

The man from Benaras

Until Independence, recalls Shaheen, Haji traded only in Benaras. He heard of the 1944 Bombay Docks Explosion, involving the freighter SS Fort Stikine. Great debris was scattered, surrounding ships sank, killing 800 people. Haji was intrigued by the city and decided to pay Bombay a visit. He never left the city.

Today, the oldest thing in the room, perhaps, is a group of taxidermied birds, which, Shaheen says, are more than 200 years old and don’t have a speck of dust inside the sealed glass case. A lot of Haji’s collection is from the Salar Jung auction by the nawabs of Hyderabad. Haji, on numerous business trips to Lucknow, Hyderabad and other cities, painstakingly built this collection.

Exquisite Mughal goblets are gilded with gold, crystal vases made by hand have unbelievable precision. A stunning tea set has Chinese garden scenes hand painted, another has Egyptian rituals, and both are as light as an empty plastic bottle. Kettles have cats for heads and the Ayatul Kursi (holy verse) is inscribed within a horse’s portrait.

Inheritance of loss

Shaheen now lives with her brother, and says the family is accustomed to excitable passers-by out on the flyover. “Many Parsis and foreign tourists park their cars on the flyover and shout out to have us at the window.

My father gladly told them stories until a jam emerged, but refused their offers to buy our collection,” laughs Shaheen. Much of it, she says, has been broken during cleaning, and some stolen by relatives.

Her biggest loss, however, is their four-lamped crystal chandelier which shattered while cleaning the mamoth piece. “Even its pieces fetched us R1.25 lakh,” she says. Shaheen now dreams of building a small museum in Haji’s name. I can see the attraction the fragility of Haji’s collection and its endurance over many decades.

I compliment Shaheen on how dust-free the collection is in spite of its location. She admits it is hard, and she has to clean some collections five times a year. “But I don’t mind it. This is my legacy, my life story,” she says.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!