Malvika Bhatia, who heads a second-of-its-kind oral archive project in the sub-continent, discusses the need to preserve the memories of India's last pre-Independence era voices

Malvika Bhatia, oral historian and archivist. Pic/Ashish Raje

ADVERTISEMENT

The sea-facing flat in Marine Drive where 27-year-old Malvika Bhatia lives, has witnessed a trunk full of stories. At one point, several decades ago, Bhatia informs that the home was brimming with people — her grandparents and nine children, included. Over the years, almost everyone moved out — many abroad, and a few even some blocks away. What they took along with them were the experiences of a life that they shared together. Bhatia, who belongs to the Kutchi community of Mumbai, which she says is as small in number as the Parsis, has always felt the need to record the complex history of her family, before they were lost forever.

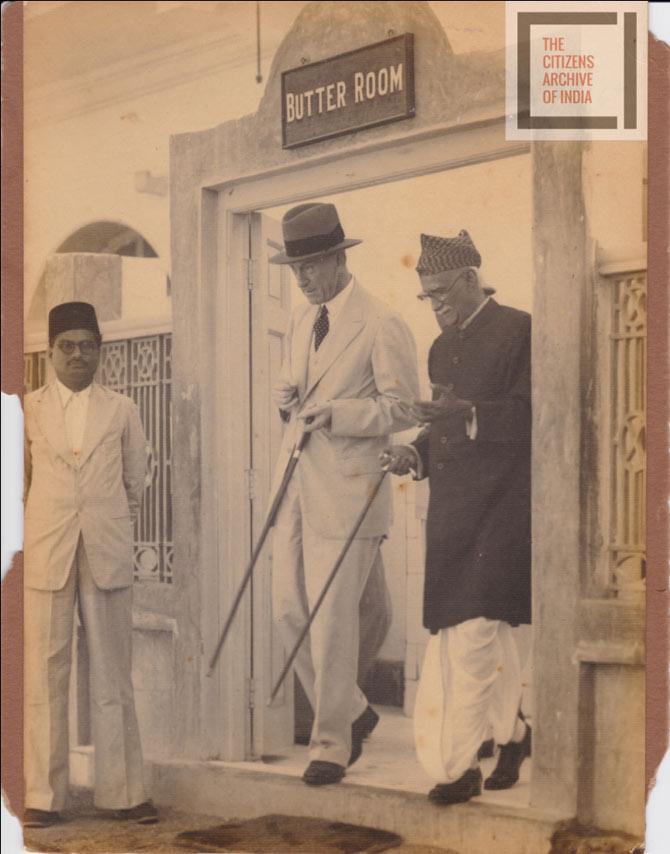

Doongursee Shamji Joshi - grandfather of CAI interviewee Pushpa Bhatia - and the Governor of Sind walk out of the Butter Room at the Karachi Panjrapole in step with each other. Pic/The Citizen Archive of India

Her educational background — Bhatia is a graduate of St Xavier's Mumbai and also has an MA in heritage education and interpretation from Newcastle University, UK — only fuelled her interests further. After spending several years working in museum and heritage education across India, Bhatia finally got to live this dream when she was invited by Rohan Parikh, managing director of the Apurva Natvar Parikh Group to head his passion project, The Citizens Archive of India (CAI). Modelled along the lines of The Citizens Archive of Pakistan, which is over a decade-old now, CAI was first started in 2016 with the aim to record and archive the personal stories of Indian citizens who've witnessed India through two centuries, using oral history and material memories.

When Bhatia took over as project head for CAI in May last year, the oral historian didn't realise that she was actually rebuilding the narrative of India through its people. While not a first of its kind, the CAI, because of its sheer scale and size, is arguably the only oral history project that hopes to cover the length and breadth of the country, in its attempt to preserve the stories. She, however, clarifies that CAI is not just a partition archive. Currently, CAI is engaged in "The Generation 1947 project." "We interview anyone born before 1947, with a story to tell," says Bhatia. "Sometimes these stories are what you might expect, where people will talk about their encounters with national leaders, or their experiences during the freedom movement or Partition," she says. "On other occasions, the stories are about the seemingly mundane — like what people ate, how they celebrated festivals or even the kind of houses in which they lived. Many times, it's these stories that stand out. They reflect how our society has changed. I love both kinds."

Mithoo Coorlawala returned to Cambridge for her graduation when she was 82, 60 years after she attended the University. Women were not given degrees at a formal ceremony until after she studied there. Pic/The Citizen Archive of India

"What is important to know is that this is the last generation that has any connect to colonial India. And, this is the only generation that can tell us about life before Independence, and how it changed or didn't, after we became a free country," says the young archivist. Bhatia says one of her most cherished interviews was one with centenarian Mithoo Coorlawala, who attended Newnham College at the University Of Cambridge from 1938-1939. Back then, they didn't award women degrees. In the interview, Coorlawala spoke about how the men's colleges were so furious when two women's colleges were established, that they burnt down the gates of their college. "There was a lot of violence against the opening of a women's college. And (they said), 'You can have a college there if you must, but you don't get degrees.' You could study, have the same syllabus, sit for the same exams, but when you passed, you didn't get a convocation. You got your degree by post. It was not a recognised thing. It was more a 'do it if you must'. That was pretty humiliating," Coorlawala told CAI.

In 1998, when Cambridge celebrated 50 years of awarding women degrees, Coorlawala and her batch were invited for a formal convocation ceremony. "So, it was at the age of 82, 60 years after she studied at Cambridge, that she actually attended her convocation ceremony," says Bhatia. The task at hand for Bhatia is, however, Herculean. She and her team of three, primarily focus on doing video and audio interviews, over multiple sessions. Currently, CAI has recorded 86 interviews over 215 sessions with 94 citizens — some subjects were interviewed together. CAI also digitally preserves various records such as letters, newspapers, documents, personal pictures, historical pictures, and other memorabilia, to supplement the oral narratives. The aim of the project is to create a publicly accessible archive for scholars, students, and ordinary citizens, who wish to listen to these stories. While CAI is still to make the archive publicly accessible over the Internet, one can reach out to the team at info@citizensarchiveofindia.org, and request to access their catalogue, says Bhatia. CAI, which is a registered charitable trust, is now seeking funds to help build its project. "My personal goal is that one day schools and colleges across the world should want to put our catalogue in their libraries and that students will be able to access it. There is a wealth of information out here that is just waiting to be heard."

Catch up on all the latest Mumbai news, crime news, current affairs, and also a complete guide on Mumbai from food to things to do and events across the city here. Also download the new mid-day Android and iOS apps to get latest updates

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!