Conservationist Valmik Thapar’s new book, Wildfire, is a fascinating chronicle of rare photographs and old wildlife narratives from across India. Kareena Gianani speaks to the author about Indian environment laws and the lacunae within, and why the Forest Department needs a shot in the arm

Valmik Thapar’s new book, Wildfire, is a collector’s delight. Spread across 500 pages are Thapar's own experiences with the environment and wild animals across the country and historical narratives by greats, including Ibn Batuta and Pliny The Elder. The last section of the book is dedicated to rare, powerful images curated by the conservationist. Excerpts from an interview with Thapar:

ADVERTISEMENT

Q. Why did you write Wildfire? What did you set out to say through the photographs and narratives in the book?

A. After working toward wildlife conservation for 40 years, having put down almost everything about the tiger, I wanted to write something that would include the very best of narratives about Indian wildlife and my own experiences of it. Wildfire is the second in the series (Tiger Fire, the first, released in 2013), and the third, which will focus on Indian birds. Cumulatively, I wanted these books to record and document the natural world from a historical point of view. I wanted to leave a pictorial record of the incredible beauty which is in danger from industrial development.

Changeable Hawk Eagle feeds on a squirrel at Todaba

A rare picture of a massive male leopard with a black panther

Q. And you decided not to focus on issues surrounding conservation in India...

A. No, not in this series. I am currently working on a book called Endangered Forests, which discusses these concerns in detail and my experience with the politics of environment.

Q. What is the major drawback of the environment laws in India?

A. The law is spread over 2,400 pages and is extremely difficult and confusing for anyone who wishes to fight for nature. What we need is for the best minds in the country to help formulate one, simple, comprehensive law so environment can actually benefit from it. A 30-page-long law which believes that spaces for wildlife are inviolate, one which is centred around people, addresses issues of wastelands across India and speaks of regreening them – we have never done that. We need a law that is bifurcated to involve state governments. We don’t need one Forest Research Institute in Dehradun -- we need several of them across the country if something has to change.

A leopard about to leap

The Narcondam Hornbill endemic to the Narcondam Islands

Q. What about reforms in the Indian Forest Service? How far do we need to go there?

A. The Indian Foreign Service (IFS) is a neglected force which needs urgent reform — it needs to be a prestigious , state service because someone who grows up around forests in Tamil Nadu being posted in Rajasthan makes no sense. People come to care about the environment they grow up around. I have always maintained that Public-Private-Partnership (PPP) is the future of Indian wildlife. Involve non-governmental individuals and locals in the matters of wildlife. The future of our environment lies in how well India harnesses talent which lies outside the government.

Andamans; a green bee-eater about to catch its prey

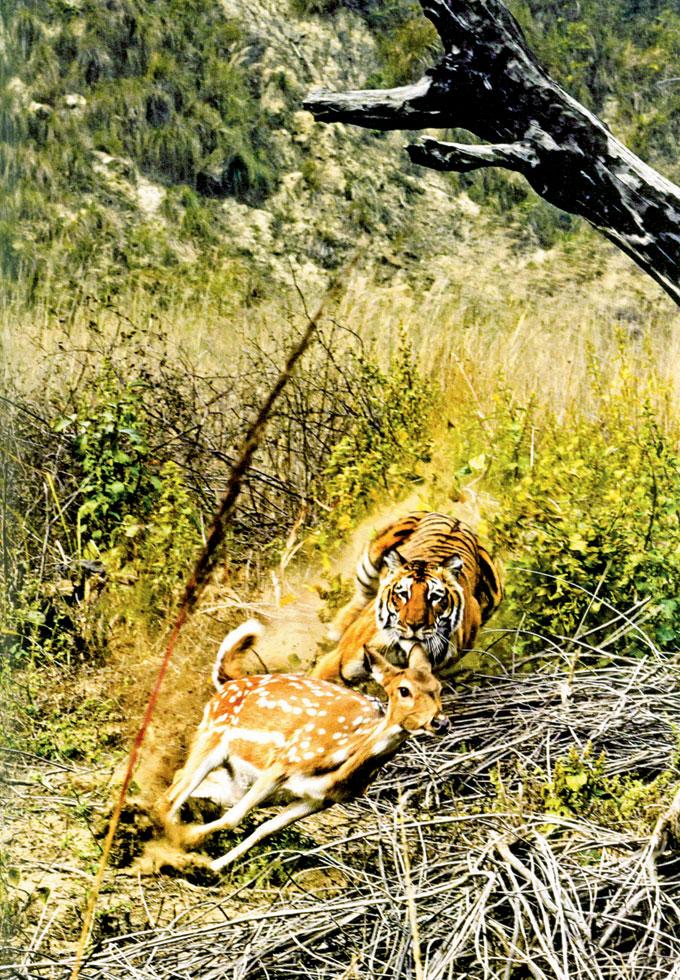

A tiger chasing its prey

Q. You have been vociferously critical of the government being in charge of Indian wildlife – why?

A. I was introduced to wildlife in 1976, with Fateh Singh Rathore, an IFS officer at the Ranthambore National Park in Rajasthan. He retired in 1991 and I have never seen a government officer as committed as him. I have worked with the government and all it does is form committees whose recommendations eventually gather dust. This is a defunct work culture and needs to stop. We need expert panels connected to the ministry and educational experts.

A surreal sight of a group of deer

Q. Your forthcoming book focuses on solutions – could you give us an example of a solution to overhaul how we run national parks in the country?

A. I have spent 10 years in Africa and observed how locals are involved in innovative tourism. What India can learn from the continent is their conservancy model. The government there supports conservancies outside the national parks that are managed by the locals. For $100, a tourist can visit such a local-run conservancy, and experience wildlife on the edges of the parks, something that doesn’t involve chasing tigers in jeeps. There are six conservancies outside Masai Mara alone. Wildlife spills out from the main park, and it is quite an experience for a traveller. Money goes back to the locals, and nobody kills the animals because they support their livelihood. We could do the same at Kanha and Ranthambore without the forest department. The Bishnois could adapt this when it comes to the blackbuck, and earn something.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!