Growing fear of AI deep fakes and misuse of their celebrityhood online is making public figures seek restrictions on use of their name, voice, photos, even dialogues. But is their brand theirs alone?

Photo Illustration/Uday Mohite

Actor Anil Kapoor had recently filed a suit before the Delhi HC, seeking protection of his “personality rights”. In an interim order passed on September 20, the bench headed by Justice Pratibha M Singh restrained 16 defendants named in Kapoor’s petition from using his name, likeness, image, voice, personality or any other aspects of his persona, including gestures, for commercial purposes. In its order, the bench observed that, “The Plaintiff also claims that the expression ‘Jhakaas’, which is a Marathi slang word, roughly translated as ‘fantastic’, ‘awesome’ or ‘superb’ in English, was popularised by him through one of his Hindi movies, namely ‘Yudh’. A perusal of the press reports and videos would show, that the manner in which he delivers the said word while speaking a dialogue, and the nature of expression is exclusively synonymous with the Plaintiff’s energetic and enthusiastic persona.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Yudh, released in 1985, was the directorial debut of filmmaker Rajiv Rai, and starred Kapoor in a double role, as two brothers separated at birth. While one grows up as a law-abiding citizen, the other becomes a henchman for the villain—played by Danny Denzongpa—and uses the word Jhakaas with a particular intonation. The word became so famous that a decade later, when CBS released an animated series on The Mask, the central character’s catchphrase “smokin” was dubbed “jhakaas” in the Hindi version.

In a suit filed before the Delhi High Court, actor Anil Kapoor had sought protection from using his name, likeness, image, voice, personality or any other aspects of his persona, including gestures, for commercial purposes. Seen here with Bhumi Pednekar at the premiere of Thank You for Coming. Pic/Getty Images

In a suit filed before the Delhi High Court, actor Anil Kapoor had sought protection from using his name, likeness, image, voice, personality or any other aspects of his persona, including gestures, for commercial purposes. Seen here with Bhumi Pednekar at the premiere of Thank You for Coming. Pic/Getty Images

Rai, who was one of the three writers of the screenplay for Yudh, in a telephonic interview, tells mid-day, “An actor’s claim over his personality has to be respected and there is no doubt about that.” However, he says, it “is also important to bear in mind that dialogue from a particular film, even though it may have been made famous by the actor, belongs to the producer, who holds the copyright”. “Dialogues are framed by the writers, with words that are in common usage at the time, which they feel will resonate with the audience. The actor’s contribution to it is undeniable but the producer holds first rights towards it,” he says.

He adds that any dialogue or song in a film is the outcome of several people brainstorming for days together. “A lot of people put their intellectual property into the making of a film. They are duly compensated for their hard work and in return, the producer holds the copyright of the film as a property,” says Rai.

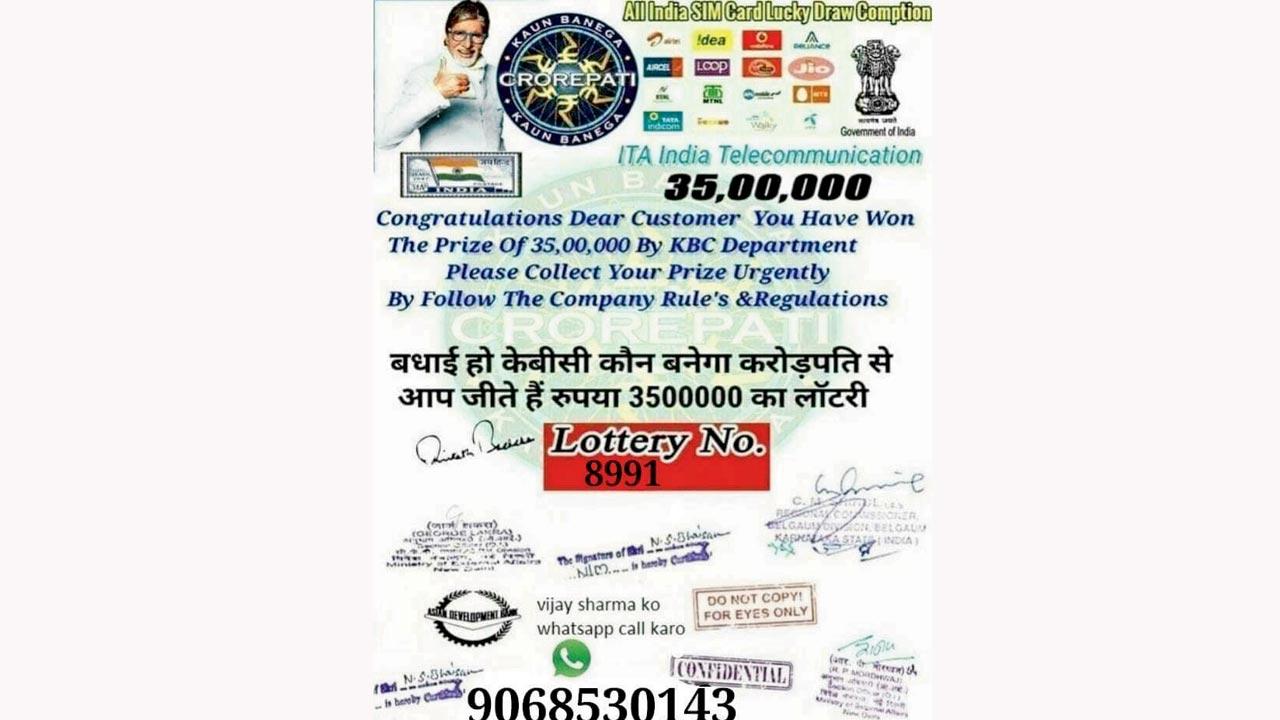

The concerns of celebrities are not entirely unfounded, case in point being the ‘KBC frauds’, where people are scammed using Amitabh Bachchan’s popular quiz show as a lure

The concerns of celebrities are not entirely unfounded, case in point being the ‘KBC frauds’, where people are scammed using Amitabh Bachchan’s popular quiz show as a lure

The development though, has given rise to mixed emotions in the performer community, particularly, celebrated mimics who have made a career out of copying their favourite stars. Many of them have been appreciated by the stars themselves, but with first Bachchan and then Kapoor going to court to protect their personality rights, performers wonder whether celebrities are going too far.

“At the end of the day,” says Balraj Singh Ghai, founder of The Habitat Studios, “you become a celebrity because you are celebrated, not feared. For that matter, even Jackie Shroff [coincidentally Kapoor’s co-star in Yudh] is mimicked a lot. There are so many memes based on certain words used by him. It depends on the stand that the artiste takes.”

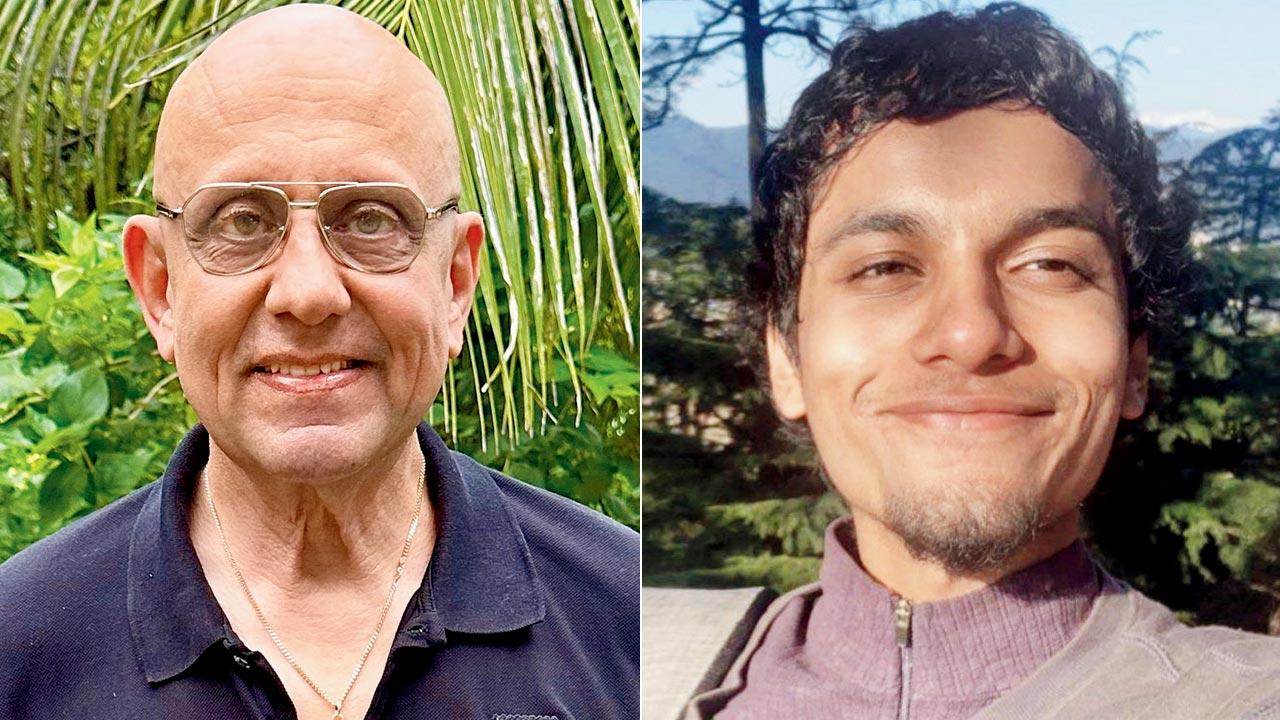

Rajiv Rai, filmmaker and Karan Saini, security technologist

Rajiv Rai, filmmaker and Karan Saini, security technologist

The Habitat hosts a wide range of performances regularly, including mimicry shows. “Jhakaas, for example, is hardly a derogatory word. If I say something is jhakaas, I say it in praise. Plus, it has recall value. Kapoor made the word famous and whoever mimics it, is only letting people relive that moment that he created,”

Ghai continues.

Legal action like this, also robs mimicry artistes of the dignity of their work. “It is because we as artistes have loved those characters, have watched them during our own evolution, that we start mimicking them. We first do it in front of our family and friends and only then do we take a stab at it on a professional level,” says Arindam Thapliyal, who goes by Jagat Didi on Instagram, and is wildly popular for his impressions of stars like Katrina Kaif and Deepika Padukone.

Arindam Thapliyal and Hardik Kanteliya

Arindam Thapliyal and Hardik Kanteliya

“Besides,” adds Sumedh Shindey, “if the actors like your act, they themselves share it on their social media. If tomorrow, I were performing and I saw my favourite actor in the audience, I would definitely do a short mimicry. That would be my tribute, not a mockery.” Shindey is a well-known voice artiste and has dubbed for Anil Kapoor’s character in the Marathi version of The Night Manager.

There’s also a thriving ecosystem of celebrity memes that are bound to be affected if actors start invoking the law. According to Hardik Kanteliya, head of content, RVCJ Digital Media, a digital company that helps client with social media engagements for their products and services, and will be hosting the first ever Meme Utsav in December, “memes are catalysts for community discussions and attention, akin to rapid, organic promotional tools”. “Even negative memes can inadvertently yield positive publicity, as acknowledged by figures like The Great Khali. However, it’s equally valid to opt out of meme engagement, recognising that creators may not fully grasp the complexities of others’ lives, and such participation can amplify stress for some,” he says.

ADG Brijesh Singh says that there is a wide range of AI models that can synthesise image, audio and even video-based deepfakes, but the same algorithm that makes this possible can also be used for detection as well; (right) Sumedh Shindey, a well-known voice artiste who has dubbed for Anil Kapoor’s character in the Marathi version of The Night Manager, says that mimicry is meant to be a form of tribute to the celebrity

ADG Brijesh Singh says that there is a wide range of AI models that can synthesise image, audio and even video-based deepfakes, but the same algorithm that makes this possible can also be used for detection as well; (right) Sumedh Shindey, a well-known voice artiste who has dubbed for Anil Kapoor’s character in the Marathi version of The Night Manager, says that mimicry is meant to be a form of tribute to the celebrity

An important aspect of Kapoor’s petition, though, which the Delhi HC, too, has taken note of, is the potential misuse of the actor’s likeness via Artificial Intelligence. Scams in the name of Bachchan’s popular quiz show, Kaun Banega Crorepati, have already been proliferating for at least the last five years. Pictures of Bachchan and the KBC logo are regularly sent to unsuspecting victims via WhatsApp, telling them that they are eligible for a “bonus round”, which will help them win significant amounts of money. All they have to do, the messages claim, is to click on the link attached. Needless to say, this is a phishing link aimed at letting cybercriminals worm their way into the victim’s bank accounts.

“The technological tools that are now freely available make it possible for any illegal and unauthorised user to use, produce or imitate any celebrity’s persona, by using tools including Artificial Intelligence. The celebrity enjoys the right of privacy, and does not wish that his or her image, voice, likeness is portrayed in a dark or grim manner, as portrayed on the porn websites. Moreover, the Plaintiff’s image is being morphed along with other actresses in videos and images generated in a manner, which are not merely offensive or derogatory to the Plaintiff, but also to such other third party celebrities and actresses,” the Delhi HC’s interim order on Kapoor’s petition states.

The bench also referred to GIFs—short, moving images used on social media—that are already in circulation and the possibility of advanced AI being used to generate realistic visual and voice clones.

In its July 23 edition, mid-day had reported how AI-based voice scams were no longer just a possibility but a reality, with 72-year-old PS Radhakrishnan from Kozhikode having fallen prey to it. mid-day’s report also mentioned a study by McAfee, a US-based cybersecurity company, which showed that 53 per cent adults shared their voices on the internet in some form or another, making them freely available for misuse.

“Up until maybe a year ago, an individual would have required access to exorbitantly priced devices to render graphics, considerable technical knowhow to train face-swapping models, and adequate source material in form of videos of the subject’s face to create a convincing deepfake. Now, however, the technology has improved quite significantly, and deepfakes, even believable ones, can be created with a single image of a subject. With these advances, an individual could create a convincing deepfake of Anil Kapoor without breaking the bank or first becoming an expert in the training of deep-learning based ace swapping models,” says AI expert Karan Saini.

“It is trivially easy to clone voices today, and generate them in real-time like an actual voice conversation,” adds Additional Director General of Police Brijesh Singh, an expert on cybersecurity and AI. “We have models that can generate text-to-speech, speech-to-text, text-to-image and even text-to-video now. However, technological detection, too, is equally possible. The same algorithm that creates these deepfakes can be used for detecting them as well. As real as the concerns of AI being misused are, it is equally possible to detect such misuse and also forensically prove it through an investigation.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!