It’s that time of the year again when the Diwali ank occupies the imagination of the Marathi reader. How are these legacy festive editions fighting new-age content creators, advertiser dominance and a fickle audience?

Retired government employee Pankaj Kulkarni has been collecting Diwali anks since 1980. His collection numbers 150. Pics/Nimesh Dave

The newspaper stand was a punctum of excitement ahead of Diwali for Mukund Kule. Together with his little friends, Kule would crowd around Girgaon’s neighbourhood magazinewallah to pick up copies of special festive editions of periodicals, known locally as the Diwali ank. The journalist-writer calls the 1980s a high point in the popularity of these editions, when picky and loyal Marathi readers would look forward to the robust special read.

ADVERTISEMENT

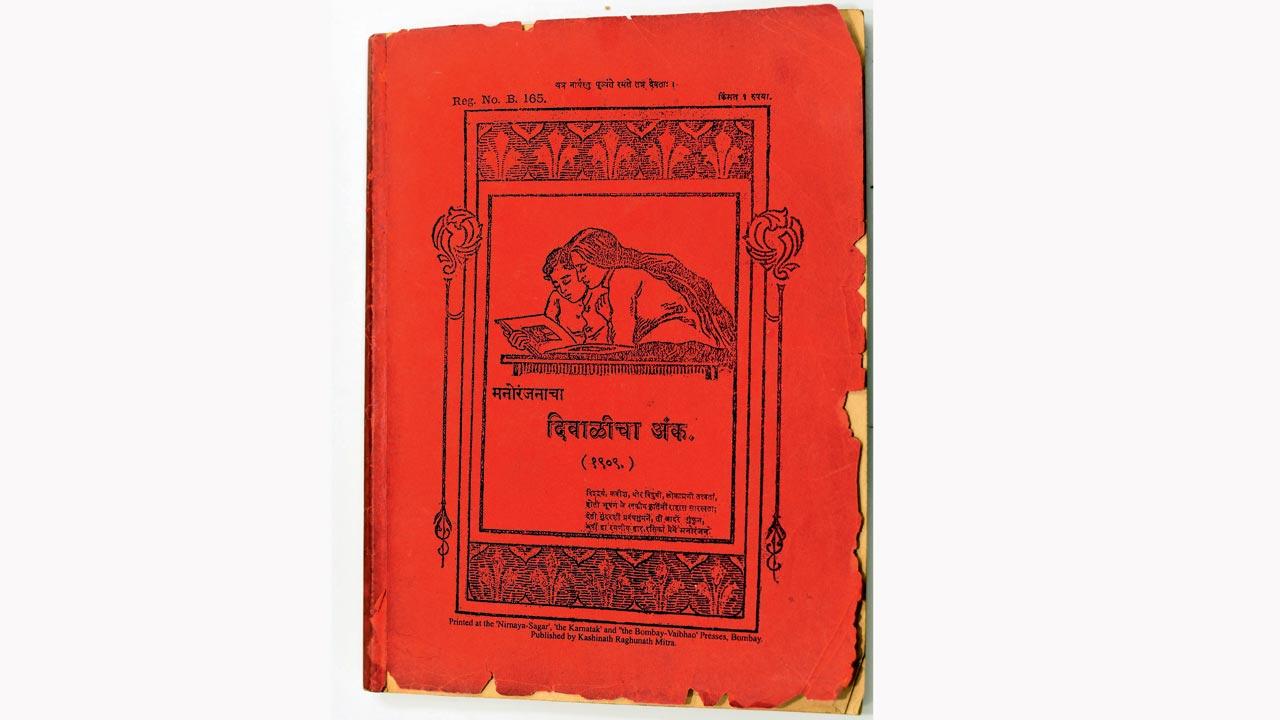

The Diwali ank was published in 1909 and called Manoranjan. It was packed with sections, including one for short stories, another for one-act plays, a few pages were dedicated to poetry, and so on. It was an experiment that piqued the Marathi reader’s curiosity. “The next year, there were a lot more anks, and the story continues to this day. Maharashtra sees anywhere between 300 to 400 Diwali editions every year,” says Kule.

Kulkarni’s prized possession—the first Diwali ank Manoranjan published back in 1909

Kulkarni’s prized possession—the first Diwali ank Manoranjan published back in 1909

The popularity though, has waned from what it was in the 1960s. The 2000s, he says, brought with its tighter budgets and the backbreaking influence of the Internet. Besides, fewer people from the community could now read in their mother tongue.

Senior journalist Sunil Karnik has written for multiple Diwali anks over the years. “It held a revered place in the Marathi household,” he says. “When a family stepped out for Diwali shopping, it was assumed that they’d pick up a festive edition or two. It was always an inseparable part of the Diwali festivities.”

Writer and senior journalist Mukund Kule has been a regular contributor to anks across Maharashtra and feels that it is the perfect reflection of the socio-political and cultural issues of the times. Pic/Nimesh Dave

Writer and senior journalist Mukund Kule has been a regular contributor to anks across Maharashtra and feels that it is the perfect reflection of the socio-political and cultural issues of the times. Pic/Nimesh Dave

The typical reader is middle class, and considers the edition a community read, sharing it with the neighbours. “Kule says, “That’s why one edition is often enough for three- four households, where not everyone can afford a magazine worth Rs 300 to Rs 400.”

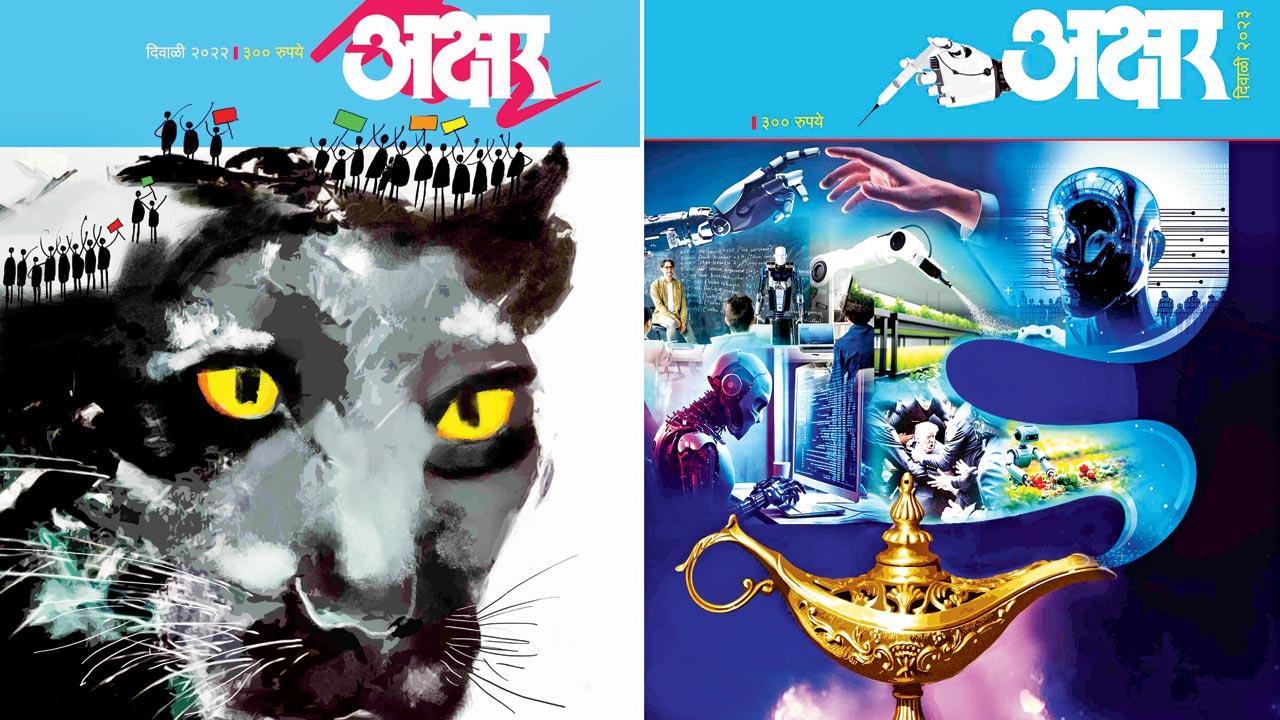

Akshar, which is considered one of the leading Diwali anks published by the Akshar group, is renowned for its quality of printing and design. Its editor-in-chief Meena Karnik is a leading name in Marathi journalism and was around to witness Akshar’s first ank when it hit the stands in 1983. “Most of the anks before ours, would have the picture of a woman on the cover, dressed in typical Marathi festive gear: a nauvari or Pathani, holding a diya. Our first cover was inspired by an article that discussed a probable bill that could curtail press freedom in Bihar.” The distributors were expectedly unhappy, “We saw a lot of opposition; until then, ank covers didn’t deal with serious subjects. But, [journalist] Nikhil Waghle, who was actively involved with the publication at the time, refused to budge and pressured the distributors,” she tells us over a phone call, the pride of sticking to editorial vision unmistakable in her voice.

In 2022 Akshar marked 50 years of the Dalit Panther movement. An anti-caste rebellion that has begun in the slums of Mumbai; (right) The 2023 Diwali ank of Akshar will feature articles of those who work with Artificial Intelligence in Maharashtra

In 2022 Akshar marked 50 years of the Dalit Panther movement. An anti-caste rebellion that has begun in the slums of Mumbai; (right) The 2023 Diwali ank of Akshar will feature articles of those who work with Artificial Intelligence in Maharashtra

Last year, the publication featured a panther on its Diwali cover, draped in the iconic purple symbolic of the Dalit Panther movement, commemorating its 50 years in Maharashtra. “This year, we have an AI-inspired cover. I do not think the Marathi reader has been fully introduced to the subject. We have included articles by those from Maharashtra working in the field of Artificial Intelligence,” she shares.

Askhar is said to have one of the highest readerships and is often sold out within hours of hitting the stands thanks to its unconventional approach and penchant to tackle non-mainstream subjects. It’s for the Marathi reader who wishes to be as well informed as those who follow mainstream English language journalism, the

team believes.

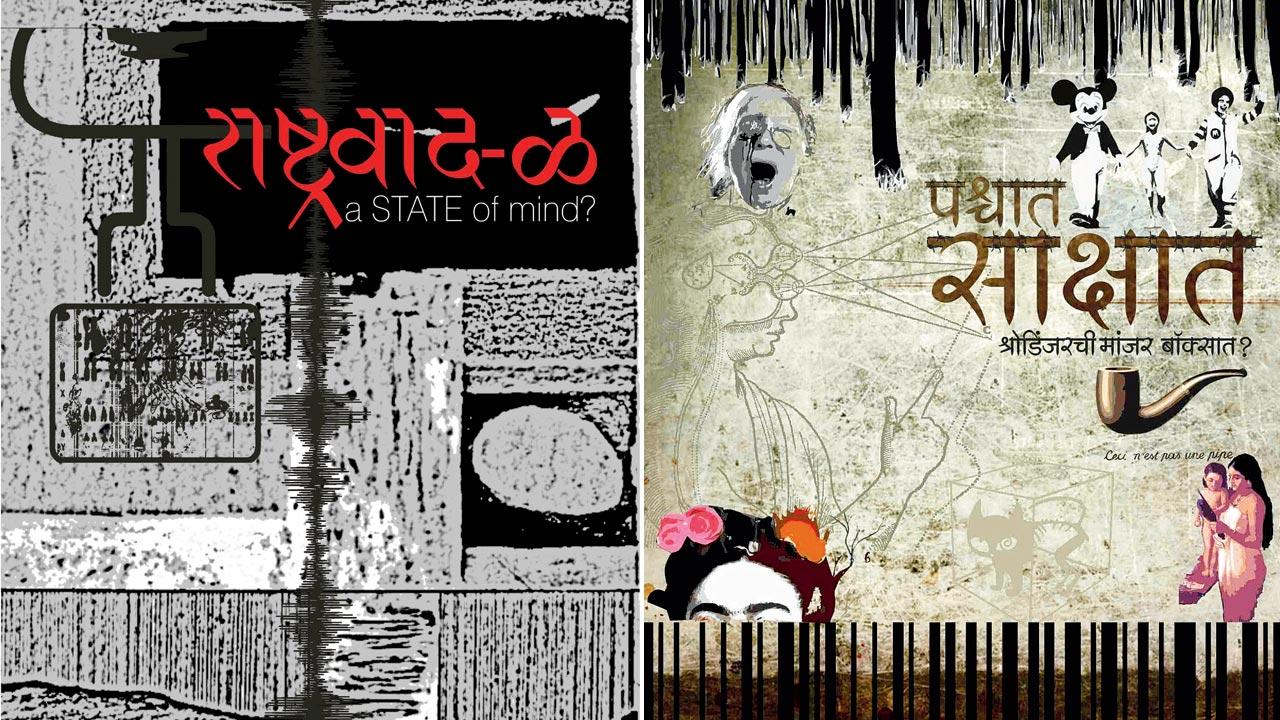

The cover of Aisi Akshare are always always graphic heavy and include Gif animation like in this cover from 2019; (right) The 2017 cover of digital ank Aisi Akshare is based on the concept of Post Truth which essentially refers to the belief system of influence rather than objectivity

The cover of Aisi Akshare are always always graphic heavy and include Gif animation like in this cover from 2019; (right) The 2017 cover of digital ank Aisi Akshare is based on the concept of Post Truth which essentially refers to the belief system of influence rather than objectivity

Between the 1960s and ’80, Diwali anks began to see the inclusion of more reportage and its position as a literary product began to be questioned. This was the time that Maharashtra was experiencing a surge of protests against caste hierarchy and writers like Babuarao Bagul and Namdeo Dhasal had caught the imagination of the Maharashtrian Bahujan samaj, says journalist Sunil Karnik. “When Bagul and Dhasal came on the scene, we had bahujans question their absence in the anks. They were until then, largely for the upper caste, a group that had easy access to literature, theatre, high art. So, we saw the birth of an era when the editors of the anks encouraged more writers from the bahujan samaj, sending them into the interiors of the state to report on stories about those who until then had no voice in leading literary products,” says Karnik.

Kule believes that these festive editions define Maharashtra’s love affair with the written word; “a barometer of just how much the Marathi loves to read and write. Today, we are seeing a lot of informative articles that are being recognised as literature, not mere reportage. I have seen many writers discuss a subject in an ank to receive feedback on it before they take it up in detail and earnest for a book. This is primarily because they know that the ank reader is a more studied reader.”

Pankaj Kulkarni is proof.

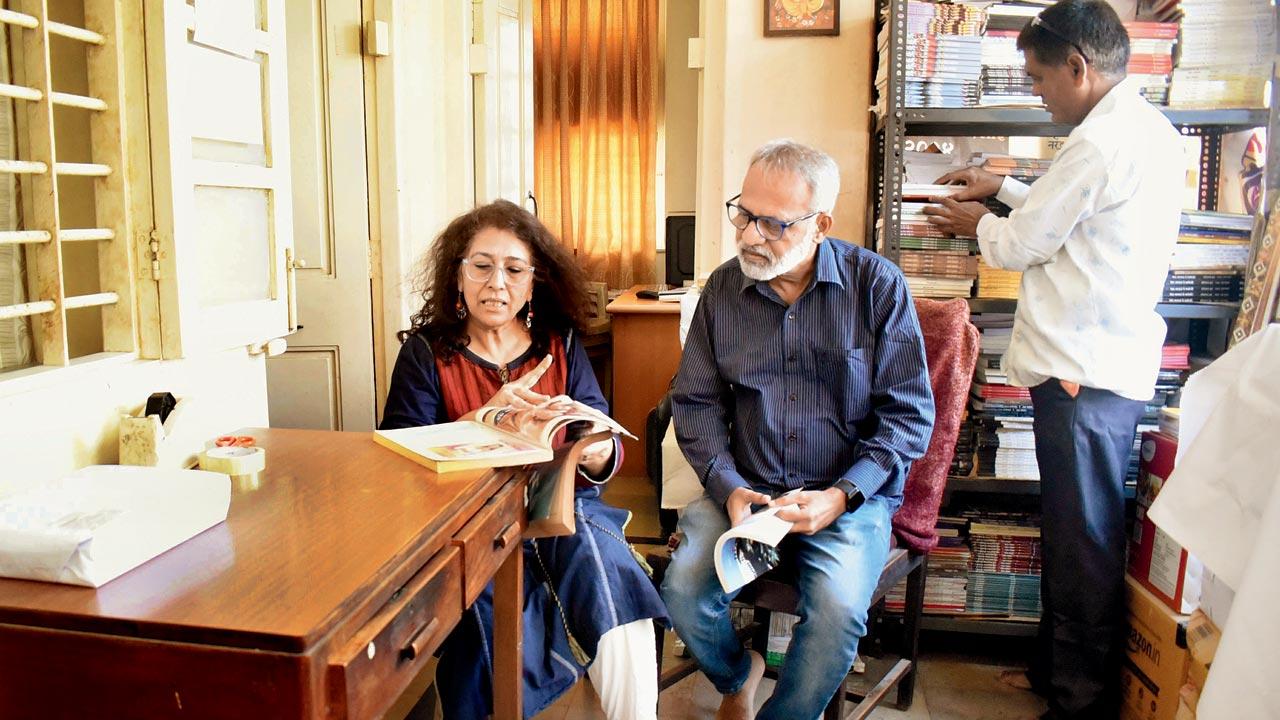

Editor of Akshar, Meena Karnik adds final touches to the latest edition with colleagues at her Dadar residence. The ank hit the stands this weekend. Pic/Sameer Markande

Editor of Akshar, Meena Karnik adds final touches to the latest edition with colleagues at her Dadar residence. The ank hit the stands this weekend. Pic/Sameer Markande

The Borivali resident’s love for the Diwali ank is half a decade old. The 63-year-old retired government employee says his first brush with the annual magazine dates back to 1969. It was before he moved to Mumbai. A school teacher brought along a trunk on a half-day and allowed the kids to browse the titles. “One of them was the bal ank [children’s edition], and I never looked back. A paternal uncle in Mumbai, who was a writer, actor and artist all in one, introduced me to the adult ank later and my taste in reading got more refined,” he recollects.

Kulkarni has been a collector of these special editions since 1980, a year after he began his career at the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation. And his prized find is the first ever Diwali ank published—Manoranjan from 1909. “It was gifted to me by a senior journalist-activist when he learnt that I am a collector. I feel blessed to have it because with that edition, readers realised what an ank could bring to the table,” adds Kulkarni.

Sunil Karnik and Monika Gajendragadkar

Sunil Karnik and Monika Gajendragadkar

The passionate collector says that he waits for the monthly magazine, Lalith, to reach him because it usually has a recommendation for readers on which articles to look out for in the upcoming Diwali ank. “I read anks because they are institutions of knowledge, and I want to be informed about my city, country and the world.”

Sandhya Narepawar, a long-time staffer of Chitralekha, a magazine with a legacy dating back to the 1950s, is now editor-in-chief of Vasa, one of the smaller, independent anks to publish out of Mumbai. The team works out of her residence. “We came into being in 2003 but most of us [on the team] were actively working in newspapers and couldn’t do much other than write articles here and there. In 2016, I took up the position full time and today we see that the voracious reader exists in the small cities and in villages. Some of our readers are first-generation literate persons from Amravati, Nanded and Kolhapur. They are young and thirsty for good content.”

Vasa has built a position as the alternate ank, having a soft spot for subjects of heft. “We get letters and calls about suggesting the subject we should tackle. The prep for the next edition kicks off a few months after the current ank is out on stands. The demand is in rural Maharashtra; unfortunately, we do not see a response from Pune or Mumbai. But then again, we do not have the muscle to reach the interiors,” she adds.

Vasa, unlike Mauj or Akshar, lacks a prominent publication house’s distribution network; it is a struggle for Narepawar. “Vasa is a passion, there is no profit in this. And we don’t get many advertisements. In fact, we try to stay away from them to maintain editorial sanctity.”

One of the major channels of distribution have been the network of libraries across Maharashtra, where members pay a separate fee to read the Diwali anks. In Mumbai, Kala Ghoda’s David Sassoon Library and Dadar’s Mumbai Marathi Grantha Sangrahalaya (MMGS) house the special anks.

Monika Gajendragadkar, the editor of Mauj, is facing another sort of challenge she is; not one that concerns readers but writers—challenge of losing thorough writers. “We tried to work with talent that writes in contemporary, catchy language, and nudged them to work on in-depth articles. But, they couldn’t cope. Their writing is overtly simple. The reader has also changed. It takes commitment to follow a story from start to finish. Today, they want it in easy, digestible bits. The future of the ank and literature in general is at risk,” she thinks.

Is going digital the way forward?

Kule and Karnik believe it is an option worth considering to keep alive the legacy. “There is restriction of space and we aren’t dependent on advertising to print and publish, but it is still too early to say where the digital ank is headed,” says Kule. Karnik thinks freedom from advertisers and their whims means that writers and editors of anks can take more risks. “The digital Diwali ank drives into a subject and are extremely well researched. That they are free from the shackles of economics that the print anks still adhere to, is redeeming for them.”

Gajendragadkar, however, wonders how the serious writer will be received by the digital reader, a generation that likes consuming content in easy, simple bytes.

The new-age ank reader is happy to read the editions online. And Sandeep Deshpande says that this tribe is growing. The Pune-based graphic designer is behind the 10-year-old digital ank, Aisi Akshare. “We are a team of five; two academics live in the US and a writer is here in Pune,” he shares about the remote working arrangement. The change in what readers expects from articles that cover social and political issues has been radical. “We had published a cover story about pornography, and anther edition looked at how comedy as a genre was changing with the times. Our reader is not age-specific; we have a mix of those who love the print editions and those born in the digital age. Our oldest reader is about 40.”

Deshpande is aware that while his print counterparts struggle with distribution and reach, he is able to reach the Marathi reader in Delaware in a jiffy. “The Marathi-reading diaspora is widespread; we have easy and instant access to them. Additionally, the digital medium is dynamic and engaging. We can slip in audio, by including the tune of a singer who we have featured choose to embed the link to an academician’s work. Even our cover page includes graphic animation. This, the reader is loving. The feedback is again instantaneous in the Comments section.”

Aisa Akshare releases an in-depth article every other day, in the week leading up to Diwali. They finally lock the ank digitally with the cover story on the day of publishing, and it remains available to subscribers for all time thereon.

Everyone though agrees that the future is going to be interesting to watch. It’s a pre-election year and Maharashtra continues to see its share of political and social unrest in urban areas and the villages. “Its cultural significance cannot be denied. The ank will continue to be the physical representation of what the state experiences and endures, a reflection of the times,” Kule concludes.

Our top 5 recos

Most Diwali anks are set to hit the stands and bookstores on November 4 and 5, the weekend before Diwali

Mauj

Ruturang

Deepavali

Akshar

Awaz

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!