Kasturba Gandhi’s 1933 diary, found accidentally and translated into English by her great grandson, is almost a one-way conversation with the Mahatma who she was separated from that year

Pic Courtesy/Gandhi Research Foundation, Jalgoan

The Ba who Tushar Gandhi grew up hearing about, fervently resisted any attempt by her husband, the Mahatma, to teach her the languages. A bone of contention between her and Bapu as he was fondly called, was her requests for notebooks, shares Tushar about his great grandmother Kasturba Gandhi. “Bapu would refuse, insisting that she first learn to write on a slate without making any errors. It was common knowledge in the ashram that Bapu wanted to educate Ba, and that she wasn’t making any efforts.” It’s one of the reasons why the Gandhi family assumed that Ba was unlettered, says Tushar over a video call with mid-day. But a chance discovery around two-and-a-half years ago, compelled them to reconsider that notion.

ADVERTISEMENT

Kasturba Gandhi reading Harijan, published by Mahatma Gandhi. In the diary, one of the most regular entries is, “Read newspaper”

Kasturba Gandhi reading Harijan, published by Mahatma Gandhi. In the diary, one of the most regular entries is, “Read newspaper”

“The staff at the Gandhi Research Foundation in Jalgaon is constantly looking for original Gandhi material, which is in need of preservation and restoration. While rummaging through a trunk at the Kasturba Trust in Indore, they found an old, frayed diary written in Gujarati. It seemed like a day-to-day record of a particular time period, so they sought permissions to bring it back to Jalgaon, where someone who knew the language, figured that it was most likely Kasturba’s diary [from 1933],” says Tushar.

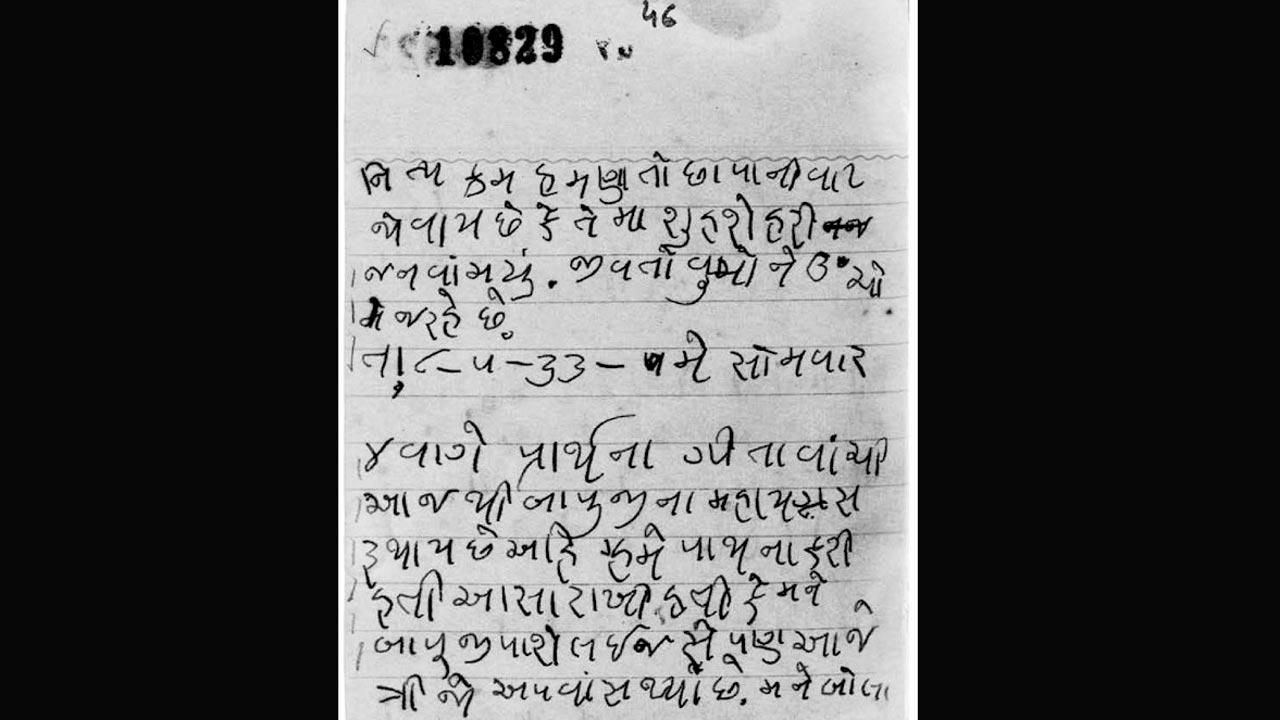

This diary entry reads, “Page 46: Morning rituals at present. We await arrival of newspapers to see what appears in them. I read the Harijan. I am very anxious.” 8-5-33, MONDAY Prayers at 4 o’clock. Read the Gita. Bapuji’s severe penance starts from today. We held a prayer here. I hoped I would be taken to be close to Bapu. But today is the third day of his fast; I have not been called.

This diary entry reads, “Page 46: Morning rituals at present. We await arrival of newspapers to see what appears in them. I read the Harijan. I am very anxious.” 8-5-33, MONDAY Prayers at 4 o’clock. Read the Gita. Bapuji’s severe penance starts from today. We held a prayer here. I hoped I would be taken to be close to Bapu. But today is the third day of his fast; I have not been called.

The family, however, was uncertain. Tushar remembers speaking to his father, Arun Manilal Gandhi, Ba’s grandson, who had written one of the first biographies on Kasturba Gandhi. His answer was a resounding “no”.

Kasturba greeting people. A rare photograph of her smiling. Pics Courtesy/Gandhi Research Foundation, Jalgaon

Kasturba greeting people. A rare photograph of her smiling. Pics Courtesy/Gandhi Research Foundation, Jalgaon

“My father was confident that she couldn’t write,” he recalls. But, as Tushar browsed through the diary, he realised that it seemed to have been written by someone who was challenged by the language. “The vocabulary, grammar and spellings were all over the place... there’s an instance where she calls a superintendent a ‘superint’,” he shares. “If Ba had dictated these diaries, and someone else had written it, such mistakes wouldn’t have been introduced,” he feels. “It had to be her writings,” says Tushar, who at this point, gets emotional in the interview. “When I started reading the diary, it felt like I was sitting with Ba in her ashram and she was talking to me. It’s been a regret of my life that I was born too late, and never got to experience Ba and Bapu first hand. Now, I felt an intimate connection with her. Tears were streaming down my face. It’s also partly because of this guilt of being so blinded by Bapu that we never even acknowledged Ba who was standing on an equal footing with him.”

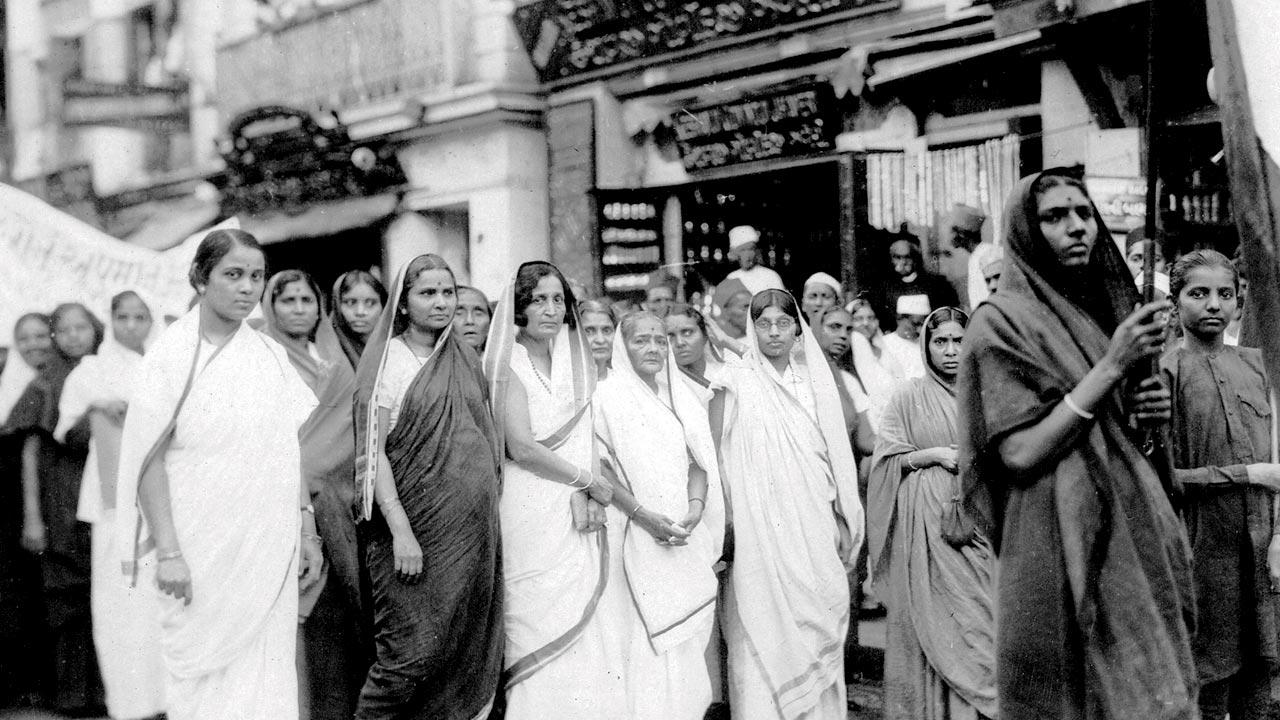

Kasturba at a women’s rally, campaigning for swadeshi, khadi and for the boycott of liquor

Kasturba at a women’s rally, campaigning for swadeshi, khadi and for the boycott of liquor

Tushar transcribed the text into Gujarati, before translating it into English for a new book, The Lost Diary of Kastur, My Ba (HarperCollins India). “This is the first time that people will get to hear from Kasturba, and in her own words,” he says. “My dilemma was whether I should impose myself on the translation, or allow Kasturba to speak through the translation. I decided to write in as faulty English as Ba’s original writing in Gujarati, because only then, the flavour would transfer to the readers. People must realise that it was a big task for her to write.”

Tushar Gandhi

Tushar Gandhi

The diary, at first glance, might seem ordinary, even very routine, to make sense of Kasturba, the wife of the Mahatma. Written between January 22 and September 30, 1933, it harks back to a time in history when Kasturba spent a better part of the year separated from her husband. We get a peek into her daily life in Sabarmati Jail, where she is arrested for participating in the satyagraha, and adopting a swadeshi lifestyle, before she returns to be with her husband, whose fast-unto-death vow has led to the rapid deterioration of his health. Her son Devadas’ marriage follows. But the flurry of activity in her life is missing in these entries: “Prayers at 4. Morning rituals. Gitaji is read always at half past 5. Give food to Bapuji...,” most of her entries read. In the prison, away from her husband, she is mostly reading a newspaper, taking a walk, spinning strands on the charkha, or waiting for his letters. “Ba was definitely reticent about sharing. It’s likely to have become second nature. As her husband’s public identity grew, she withdrew further into a shell. Her role was to manage the ashrams she lived in [with her husband and other community members], but she’d become a silent observer when she came in contact with outsiders. She probably realised that her husband was too transparent, and [from the diary entries it becomes clear that] she didn’t want the same for herself. It’s why her entries seem curt. Frugality, which had become a way of life, seems to have transferred to the use of language too,” he says.

Tushar feels that the diary was Kasturba’s way of communicating with Gandhi. He points out that it opens with “accept my humble prostration”—a standard address in a correspondence to an older or respected person. “My assumption is that since they were separated for most part due to the circumstances, she chose the diary as a means to speak with him. But, I am sure, she never gave it to Bapu, because had he got the diary, he’d have returned it to her with many corrections.”

What he, however, feels the diary does is reveal the contrast between reading Bapu and Ba. “When you read Bapu, you learn about the significant events [of India’s freedom struggle] and his own ideology, which he discusses at length. You don’t get details about the day-to-day life led by Mr and Mrs Gandhi. But Ba’s writing takes you there, and closer to their routine. When you read their writings together, you have a complete portrait. For the first time, you have a more vivid and real glimpse of their life in the ashram.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!