A new book featuring 110 artefacts from Goregaon’s Archdiocesan Heritage Museum hopes to enlighten people about Christian art from the city, which was not only inspired by Indo-Portuguese sensibilities, but also infused elements from other faiths

Joynel Fernandes, assistant director, Archdiocesan Heritage Museum, has spent the last six years working on the coffee table book cum catalogue, which shines light on the rare artefacts in the museum’s collection. Pic/Sameer Markande

Not too long after the institution of the Archdiocesan Heritage Museum on the mezzanine of St Pius X College, Diocesan Seminary, Goregaon, its director Fr Warner D’Souza remembers receiving a peculiar request from the Art Gallery of South Australia. This was a couple of years after the museum, the first dedicated to Christian art in Mumbai, came into being in 2011. “At that point in time, the gallery wanted to borrow a couple of our pieces for display. But, they asked, if we had a catalogue to show them [before they could decide],” he recalls. It is then that Fr D’Souza realised that they’d have to “come up to speed,” if they were to work and collaborate with other museums across the world. After a lot of deliberation and discussion with members of the Archdiocesan Heritage Committee (formed in 2006), now called the Committee for the Preservation and Promotion of the Artistic and Historical Patrimony of the Church, they felt that instead of a catalogue, they should publish a book, which would “illuminate people’s minds about Christian art and also talk about processes that went into their creation”.

ADVERTISEMENT

Nearly eight years on, as part of its 10th anniversary celebrations, the museum has released a coffee table featuring 110 artefacts. “Our collection is extremely vast. So, the pieces we selected [for the book] were those that we felt best represented this collection and would draw interest [in Christian art],” says Fr D’Souza, about the artefacts spanning nearly 400 years and different geographic origins. “We also have ones as recent as the 1960s. The idea was never about having the best and shiniest. We wanted to show beauty even in simplicity. For instance, in the early 1900s, we had zari zardosi work on the vestments, which was not that grand as what was seen in the Portuguese Era. [These find a mention in the book, too].”

Fr D’Souza says a young expert is credited with much of the work that went into this book: the “star of the project” is 27-year-old Joynel Fernandes, who is assistant director at the museum. She took charge of researching and writing the book six years ago. Fernandes, who we meet at the museum early on a weekday morning, worked closely with the priest, as well as the museum’s curator RK Moorthy, academician and author Dr Fleur D’Souza and the Catholic Communication Centre, to put together this one-of-a-kind exhaustive work, which is equal parts descriptive, informative and illustrative.

The book, which opens with a detailed chapter on the history of the Archdiocese of Bombay by Dr Fleur, has been divided into thematic sections based on the objects. These include the Sacred Vessels; Appointments of the Altar; Ceremonial Accessories; Processional Accessories; Statues of Christ, the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Holy Family and the Saints; Halos, and Crowns; Bishop Insignia; Sacred Vestments and Altar Parts. “The idea was to show the different components that one sees visually inside the church,” says Fernandes.

Apart from this, it also shines light on the contribution of the local woodcarvers, goldsmiths, painters, needle workers, who, says Fernandes, blended European art to the oriental environment. A recurring symbol in Indian Christian iconography is the lotus flower that has its origins in Buddhism; the book also features a bird-shaped peristerium, dating back to 1640-81, which bears resemblance to Islamic style of art; Kutch-inspired artwork is seen in the the absolution jug and salver, which is used to catch water poured from the ewer during the liturgical hand-washing ceremony. “There’s a know-how section, where for certain artefacts, we offer insights on the making of the works of art, the artistic style, the tools used, and the technology employed,” shares Fernandes.

The book also features illustrated photos, designed by the CCC, to highlight the anatomy of certain artefacts. “This is very important, especially because some of these religious artefacts have long been replaced by simpler designs. So, there is very little knowledge about them,” she says. To illustrate, Fernandes shares the example of the Indo-Portuguese Cathedra, also known as the Bishop’s throne, donated by the Church of St Michael, Mahim. This ornately-designed wooden chair comprises an elegant crest rail, decorated with S and C scrolls; the seat rests on four cabriole legs, which terminate into a ball and claw feet rendition.

For her research, Fernandes pored over books, catalogues and historical texts, especially those on the history of the churches of Bombay and Goa, at the museum’s library. She also referred to texts available at the Metropolitan, Louvre and Vatican Museums. “What’s interesting about research is that you will never find what you are looking for in a particular archive or text. It requires patience and perseverance, but that’s the joy of it. It’s an interesting journey, and given the opportunity to start again, I am sure there will be new connections that would emerge,” she feels.

Unfortunately, the beauty of Indian Christian liturgical vestments and objects have deteriorated over time, feels Fr D’Souza. “That’s the stark reality. The craftsmanship and artisans we had in the past were superior and fantastic. So much of this talent has been lost to technology, and even then, technology hasn’t been able to replace what human hands once made. And that’s what we want to draw people’s attention to,” he says. Fernandes adds, “It’s true that we are slowly moving away from our religious and cultural connections. There was a time when art and paintings were used to enlighten people, especially the uninformed, about faith and God. Today, it’s ironic that [despite being so aware and knowledgeable about everything around us], we need to turn back to this same art, to appreciate religion.”

Head of the Crucified Christ, Church of Our Lady of Bethlehem, Dongri (1600-1630)

The head of the Christ forms a part of a sculpted corpus that suffered serious damage due to a mysterious fire that plagued a Good Friday service in the 1600s. A major portion of the back, neck and arms were consumed in the flames. The parishioners viewed this catastrophe as a bad omen and had the body wrapped and placed in the church attic

Peristerium, Church of St Francis Xavier, Dabul (1640-81)

Executed in precious metal, the Peristerium served as a vessel for the reservation of the Holy Eucharist. It was suspended above the altar of a medieval church. However, this method of reservation was prohibited due to easy theft and desecration witnessed during the Reformation (1517-1648) and the terrorising years of Iconoclasm

Chalice, Paten and Box, Gifted by St Pope Paul VI to the Archdiocese of Bombay, 1964

Pope Paul VI celebrated the Holy Mass at the majestic Cathedral of Orvieto, Italy. As a token of the city’s love and as a lasting souvenir of the event, the people of Orvieto gifted a chalice to the Holy Father. The design of the Holy Cup was inspired by the architecture of the Cathedral. When the Pope visited Bombay to preside over the 38th International Eucharistic Congress, he desired to donate this gift, which was his “most precious”

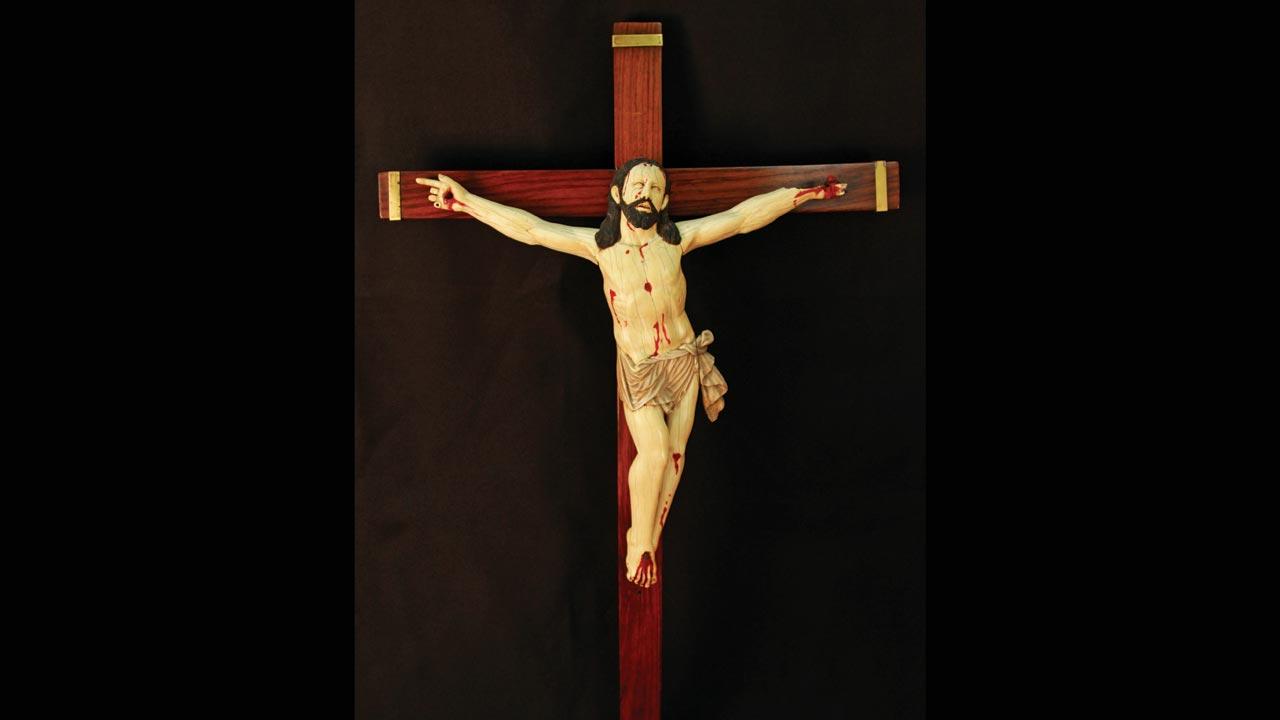

Crucifix, Church of St John the Evangelist, Fort (1700 – 1750)

This particular ivory image on rosewood serves as a true example of “sincere” art. The word “sincere” has an interesting artistic origin. The charisma of a sculpture turned redundant when at the final hour, the chisel slipped and damaged the delicate nose. Much to the disappointment of the artist, wax had to be used to reattach it. However, if the artist succeeded in executing a statue without using wax, that object would be hailed as “sincere” work of art. (Latin: “sine” – “without” and “cera” – “wax”).

Cathedra, Church of St Michael, Mahim (1620-1660)

Traditionally, in the Church, the word cathedra was metaphorically used to refer to the Office of a Bishop, without a reference to a tangible throne. The chief church of the diocese into which the bishop’s official cathedra is installed is called a cathedral. ALL PICS AND TEXT COURTESY/Archdiocesan Heritage Museum

For details on Archdiocesan Heritage Museum book (Rs 2,000), Call 9820242151

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!