That Covid reset the customer psychology was just one end of the vibe shift. Has it also redefined the role of a fashion designer?

The model in a Maynah cape set by AMPM

Something has shifted in fashion’s centre of gravity. An aura of mystery that enveloped its designers is not a groovy little secret anymore. The idea of waiting for the next fashion week to find out what such-and-such designer label will do next is yesterday’s news. “The days of designers referring to their brands or garments as ‘iconic’ are long over. That kind of attitude puts customers off the brand; it implies that the designer knows better than you,” thinks Sabina.

ADVERTISEMENT

Comedienne and YouTube personality, Bhuvan Bam in braille embroidered kurta by Kunal Rawal

Chopra, who over the two decades has mentored and championed an extensive list of promising young talent. In this lost old world, a brand that had established its influence, could count on a long reign. In the post-pandemic world, however, there are no guarantees. COVID has altered our relationship with clothes—and our bodies—and this development has not gone unnoticed by designers. When Kunal Rawal launched his menswear brand 15 years ago, his father had suggested that he devise a plan A, B and C; the latter would need to factor in a doomsday-like scenario. “I never understood what he meant then, until the lockdown. It was a frightening and uncertain time for designers. It made us aware that the ‘business as usual’ approach was no longer acceptable. Agility is key to survival,” Rawal tells mid-day.

The model is wearing a SWGT dress made in 100 per cent mulberry silk and paired with a handwoven chanderi silk jacket

The model is wearing a SWGT dress made in 100 per cent mulberry silk and paired with a handwoven chanderi silk jacket

The changes in the market means that a designer is no longer dealing with a singular client profile. “To reach this new audience, a designer must adopt an acutely personalised approach, sop up influences like a suction vessel, listening to people across diverse societies, cultures and gender identities instead of being a smug know-it-all in the room,” says Pranav Misra, creative director at Huemn, who recently added the role of executive-chief to his title. The gender-diverse, youth-focused brand celebrated its tenth birthday last year with a collaboration with Pepsi India—making Huemn the first Indian fashion brand to partner with the soda manufacturer.

The models are dressed in “diversity” puffer jackets by Huemn

More immediately, though: the aspects of what it means to be a designer seems to exist in the realm of cynicism, uncertainty and doubt. Has being a fashion designer really come to this? Nachiket Barve takes a pause-and-think moment before answering our query. “It is now a more complex, crowded space [for designers] for sure, and it is not enough to make great clothes.” The Mumbai-based fashion and costume designer is clear that he must take note of fashion while taking care of marketing and digital performances. “We have to constantly switch between the roles of CEO, stylist, photographer, cultural advocate and creative collaborator.”

Models dressed in brocade sherwanis by Kunal Rawal

There is a Hindi term for tailor—darji. “But is there one for a designer?” Gaurav Jai Gupta, wonders. “I don’t design to prove a point. I design because this is what I know best,” the founder of Akaaro says plainly.

Squaring up between private and public lives on social media, visual toasts and shoutouts, celebrity collaborations and supercharged launches, digital and brick and mortar marketing, a designer is doing a lot today. “I see my role as a curator of influences and experiences rather than a creator,” Amit Aggarwal admits. “We are at a point where the very definition of what it means to be a designer is being rewritten. The artistic process is probably more driven by understanding and utilising the differences between when to be a designer, and when to assume multi-hyphenate roles to develop a customer following across multiple platforms,” the creative director of the eponymous bridal couture brand explains.

The model in a Nachiket Barve ensemble

The whole vibe shift from runway shows being exclusive industry events to exclusively-for-everybody Instagram shows has not only rejiggered how fashion is designed, presented and consumed but powered the rise of direct-to-customer brands. “There has also been a paradigm shift from erstwhile society swans to celebrities to now Instagram-famous names. There are no gatekeepers to the industry anymore. Everybody is a publisher, including designers who have turned into stylists. They are also editors of photos and content on social media,” says Barve.

Radhika Nair in a handwoven indigo cotton tunic paired with textured bomber jacket and Jamdani coat by Akaaro

Customers, it seems, are the new power brokers within this intricate hierarchy. All that designers can do is come up with scientific ways to charm them. “For us, social media has become more of a portal into the way young India thinks. To keep up, we must add value by being specialists; you have to think like a client to better understand them,” says Rawal.

The changes fashioned by the flat screen do come with potential downsides however. “In between, we started playing it safe and designing products for everybody. We were not thinking like designers, we became manufacturers of clothes,” explains Anirudh Birla, chief marketing officer at AMPM. “We can’t be a label that designs everything from a T-shirt to a lehenga.”

Actor Richa Chadha in a metallic winged saree and hand-sculpted corset by Amit Aggarwal

A “pull and push” approach, Birla says, is what helped double his brand’s revenue in the last one year. “Inauthenticity is the quickest way to kill a brand. We need to understand that we are consumers too. What do we look for in a product [designers must ask themselves]?,” he says. Birla with creative directors Ankur and Priyanka Modi, therefore turned focus on developing the brand across retail spaces, experiences, product categories and price points, and then looked at social media. “The strategy worked because we realised it’s not always about the latest designs, shows, collaborations or hashtag activism, but a brand’s authenticity that consumers recognise and reward.”

The most successful designers today are positioning themselves as the celebrant—rather than the celebrity—of their customer community and working with them to fulfil the brand’s mission. “In some sense, every single person on the app is their own media outlet. This presents designers with a unique challenge to use new thought and tools to offer an individualised customer experience,” says Aggarwal of the new generation of savvy shoppers. Brand loyalty is not a sure thing anymore, Aggarwal reasons using the analogy: It’s no longer the case of sticking to a loyal brand of butter.”

Sabina Chopra

Loyalty might not be entirely dead, but it is playing out differently. With burgeoning online subcultures and direct-to-customer business models, the new look will come in different guises, with Chopra going a step further to predict that, branding will no longer be required in the next few years. “We will see less and less of a client walking into a multi-designer store and asking for a specific designer’s creations [unless you are shopping for bridal wear].”

The considerations that shaped a designer’s reputation have turned upside down, switching idolatry to customers as their new muse and—creating products that align with their worldview. This, Chopra asserts, will determine whether a customer will become a loyal patron. “It’s like reviewing a customer’s KYC but in a conceptual way, and building products where the designer says to them: I know you, so I will offer you this.”

My biggest challenge and how I’m tackling it: Fashion designers on the Indian market

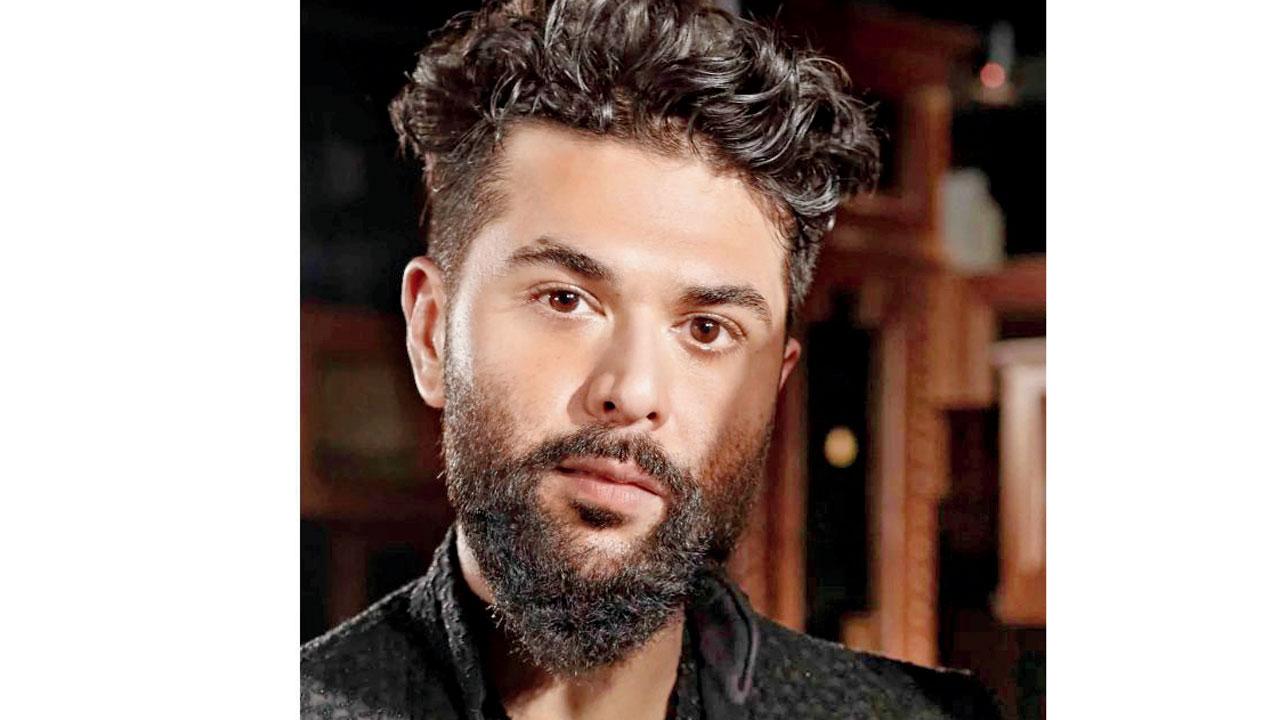

Kunal Rawal, 36

Brand: Menswear

How old: 15 years

India is an exciting and diverse market, but it is also uniquely challenging because no one-size-fits-all. Each city is a unique market with a different weather pattern, demographic, language, culture. It’s like making clothes for 16 countries in one. As a menswear designer working in the trousseau market, I have learned to tailor my thinking to align with the clients’ individual way of life, especially traditions and customs. It also means investing in people and processes across design, sales and marketing methods suited to local markets, and doing it consistently across all channels so that the brand becomes instantly recognisable.

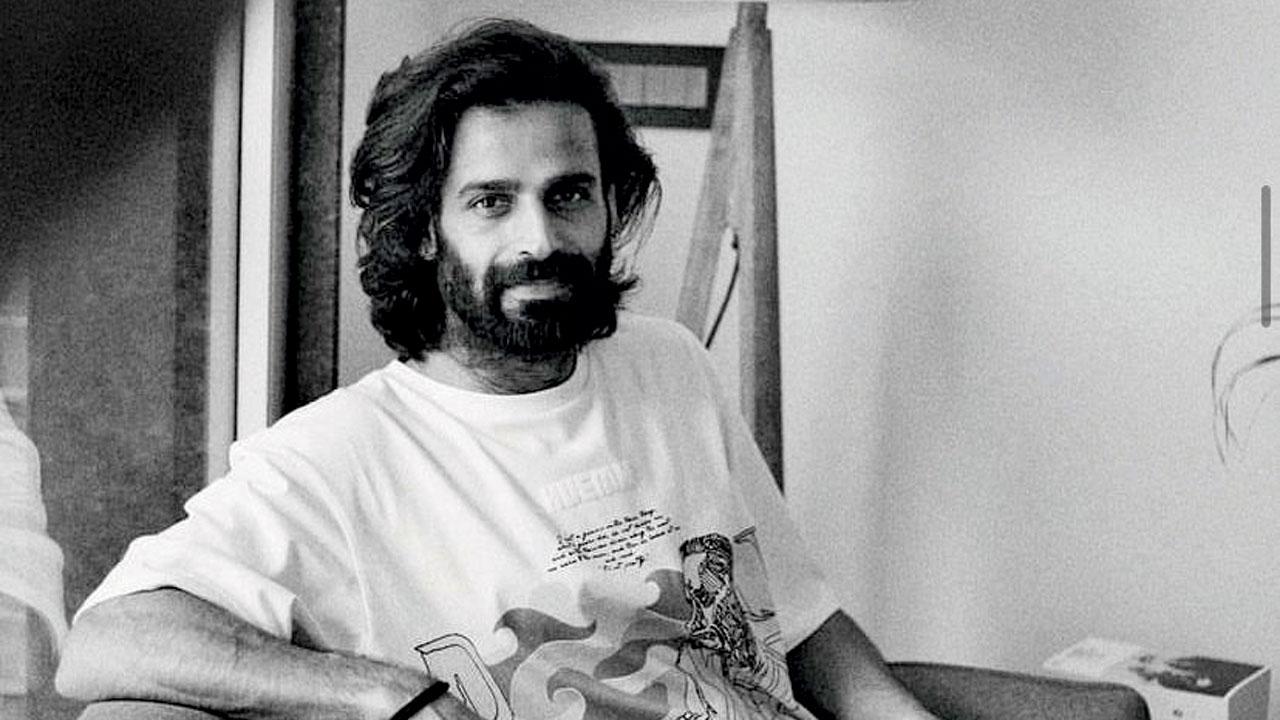

Pranav Misra, 38

Brand: Premium ready-to-wear

How old: 10 years

In its initial years, customers found our brand ethos and purpose of celebrating individual expression through diversity, either too cool or way too intimidating. The customer demands transparency, accountability and authenticity from a brand in return for a purchase. I am a storyteller, and kapda (clothing) is another

layer to that storytelling. But how can I tell a culturally credible story in English, a language that is not native to me? I am from Lucknow, and grew up speaking in Hindi. We took a step back to regroup and decided to make Hindi a large part of our brand content.

Anirudh Birla, 38

Brand: Everyday luxury

How old: 20 years

For us, the biggest challenge was that the Indian designer market was too limited and within that scope, the ready-to-wear (RTW) segment too niche. Spending on clothes for everyday social lives was unheard of—those budgets kept exclusively for weddings, festivals and special occasions. We decided to go back to the drawing board, and reinforce the personality of our brand, which is minimal, everyday luxury. We were also fortunate to have the financial muscle to back our marketing and retail capabilities. Every time we had money, we decided to invest it in either opening a new store or strengthening our existing spaces rather than spending it on a fashion show. We managed to crack the RTW market by being fearless with our approach, and that has made all the difference.

Nachiket Barve, 41

Brand profile: Modern festive

How old: 15 years

It goes without saying that the longer a brand is around, the more challenges it will face from competitors and a changing market. The key issue then is how can a brand stay genuine and grow organically over time, while trying not to get blindsided by the populous alleys of social media. Instagram can’t take precedence over good design. At the end of the day, you have to know that you can’t please everybody. Designers are, after all, not in the business of selling white bread.

Amit Aggarwal, 42

Brand profile: Bridal couture

How old: 10 years

Today’s customer wants to be enthralled on multiple levels. Because it is in human nature to understand concepts you have already seen or heard, for instance, a brand that’s reinventing the past is able to easily communicate this on social media. But what we imagine through our clothes is an abstract future, and to translate this through compelling brand narrative was a struggle. The audiences online don’t want a PhD dissertation on the brand, and so we decided to break our messaging down to tiny visual frames to include concise information on our inclusive ideology, why we design, how a product is developed, the emotions linked to our outfits, etc.

Our first collection was loved by the Indian and international press, but it didn’t quite resonate with the customers. It’s only in the last four years by way of carefully crafted storytelling that our products are finally in people’s cupboards.

Gaurav Jai Gupta, 41

Brand profile: Contemporary textiles

How old: 12 years

Working in the fashion industry while not playing to the gallery hasn’t been a cakewalk. At the start of my career, I allowed myself to get influenced by how the media and industry functioned. Intuitively, my work came to my rescue. I like the process of making designs, perhaps more than the selling part. To make customers understand good design or fashion continues to be an uphill climb. I remember being told, ‘yeh toh aapko karna hi padega’. I understand the importance of updating Instagram and staying visible, people assume you’re dead if you don’t. But I like to do less and at my own pace. Something about this approach oddly has worked for my bespoke brand; I have not only survived but also grown. I always have had a set base of loyal customers; it is small but rock solid. A customer who looks for something new every other month is not my core customer anyway.

Shweta Gupta, 35

Brand profile: Indigenous craft-based separates

How old: 4 years

I decided to become a designer to make sustainable, quality clothes that focused on supporting local indigenous communities. And these take time and effort to produce as it’s made using traditional techniques. The scale of my operation is small, which makes it impossible to keep up when customers’ demand constant newness and capsule collections every month. While the obvious solution is to grow my buyers’ list by producing more clothes fast, and invest the money back into the business and employ more people—in reality, how is this model sustainable for the environment? |

Also Read: Of style and warmth: Here’s how to style bodycon clothes during winter

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!