After Eknath Khadse raises suspicion over contract to kill 3 lakh rats in Mantralaya, Sunday mid-day tracks the city's ambitious fight to battle the menace scurrying on fours

Farooq Dhala and Irfan Machiwala, from Mahim, say that Night Right Killers are the best measure against the rodent menace. Pics/Suresh Karkera

ADVERTISEMENT

Seated on a comfortable, high-backed chair within an air-conditioned room on the second floor of a Grant Road school building, Dr Rajan Naringrekar shares a most uncomfortable but typical Mumbai story. "Every day, an animal lover in my neighbourhood, leaves out food for the stray dogs of the area. But, what happens to the leftovers? It becomes a feast for the rats."

Perhaps he could try explaining that these actions are unsanitary and contribute to a larger health problem in the area? It's not as simple. Such a confrontation, says Naringrekar, insecticide officer at the Health Department of the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), might ruin neighbourly relations. Like elsewhere in the city, here, too, rats have their space secured while humans scuttle around them.

A Vikhroli resident we spoke to about the city's rat menace, responds: "We have given up and so, we keep food for them at the rear window. They come, eat and go away; no destruction for now." Everyone in Mumbai has a rat story. None, however, more famous, at least in the last one month, than senior BJP leader Eknath Khadse.

Speaking at the state legislative assembly on March 22, Khadse said that according to a government response to an RTI query, in 2016, a contractor killed 3.2 lakh rodents within a week at the government headquarters, Mantralaya. He then went on to do the maths: 45,628 rats were killed per day while the per minute rate would be 31.68 rats. When the BMC did the same job, the results were: two years to kill 6,00,000 rats.

BMC Insecticide Officer Rajan Naringrekar says that rats are picked up from various wards in the city every day and checked to see if they have the plague bacteria. Pic/Suresh karkera

Sleepless in Mumbai

While Amitava Kumar's 2013 title, A Matter Of Rats: A Short Biography of Patna, was admittedly about the Bihar capital, the professor of English at New York's Vassar College writes about the physiology of rats that will have anyone fascinated - and perhaps especially Mumbaikars, who often wonder how large rats enter homes through really tiny holes. "Rats are one of NYC's greatest obessions. They are neither as invincible as bed bugs, nor as common as cockroaches, but they make for more scary You Tube videos. Of course, no trip to the waterfront goes unrewarded by a rat-sighting, and they are a constant feature of the city's subways and sewers. During those nights in Patna, when I lay awake in bed listening to the movements of rats in the dark, odd details from the New York magazine article would come to me. Rats can get pregnant within 18 hours of having given birth, and can produce a litter 21 days after impregnation. They can swim for more than half a mile, tread water for three days, and, as my mother alleged, sometimes even emerge through the toilet bowl. They can gnaw through concrete and collapse their skeletons to fit through a hole no bigger than a coin. Rats can also go two weeks without sleeping."

Four years ago, Farooq Dhala and Irfan Machiwala took it upon themselves to control Mahim's rat menace. They would take BMC's Night Rat Killers around the area, staying up between 1 am and 3 am, to ensure the rodents were killed. On some days, they say, an NRK would kill as many as 100 rats. Pic/Suresh Karkera

The sleepless nights in India's financial capital, not just concern rats, but also the humans who take it upon themselves to fight them. Four years ago, five Mahim residents came together to battle the rat menace in their area. Today, two of them - Irfan Machiwala and Farooq Dhala - have managed to stay with the plan.

"If you were standing on the road, the rats would scurry over your feet," says Machiwala, who lives on L J Road. Several letters and SOS calls to BMC's Pest Control department finally yielded response and, one day, civic workers arrived with aluminium phosphide tablets. The tablets, Naringrekar explains, release poisonous phospine gas when they come into contact with moisture. They are dropped into rat burrows, which are then covered with mud or newspaper. The rats, in their bid to escape the poisonous gas, will step out of the burrows and can then be caught. However, ideally, the gas that they breathe would be enough to poison them. "We did this in the entire area covering LJ Road, Cadell Road, LJ 2nd Cross Lane, Dargah Street and the Mahim Fort Area. The next morning, we went back to the roads around 9 am and saw just a few rats." Machiwala says they were told that 9 am was too late. "The sun rises at 6 am and carrion birds such as crows and eagles would have picked up the dead rats by then." The response did not satisfy the two men, whose motivation to curb the menace was not just a question of hygiene alone, but also to have a safe roof over their heads.

A Rentokill PCI staffer placing a rodent bait station at a Malad West office district last week. The firm says they get as many as 15 calls for their Pied Piper Service daily from Mumbai. Pic/Nimesh Dave

Dhala brings to mind a recent viral video where a three-storeyed Agra building whose foundations had been weakened over the years by rats burrowing underground, collapsed into dust in a matter of seconds. Dhala, who lives in an early 20th century building on LJ Road, says in 2012, he realised that the foundation of his building was being chewed away by rats. "I feared that one day not just mine, but other buildings in my area would also collapse." Machiwala and Dhala realised that more needed to be done.

"We had heard of night rat killers (NRKs). Men who would operate between 1 am and 3 am. That they had to kill a minimum of 30 rats per night for payment meant that they would work effectively. At that time, it was not a service that was well promoted. The men would shine a torch in the rats' eyes, blinding them and then strike them dead with a lathi, before dumping them in sacks," says Machiwala. Dhala, who has kept detailed accounts of not just the letters sent and received, but how many rats were killed and when, says in four years, 5,000 rats were killed in the area.

They have other statistics. On some days, says Machiwala, one NRK would have even killed as many as 100 rodents. And, Dhala says that while the rats in the Shivaji Park area weigh only 100-200 gm, in Mahim, thanks to all the garbage and food available on the streets, their weight has gone up to as much as two kilos.

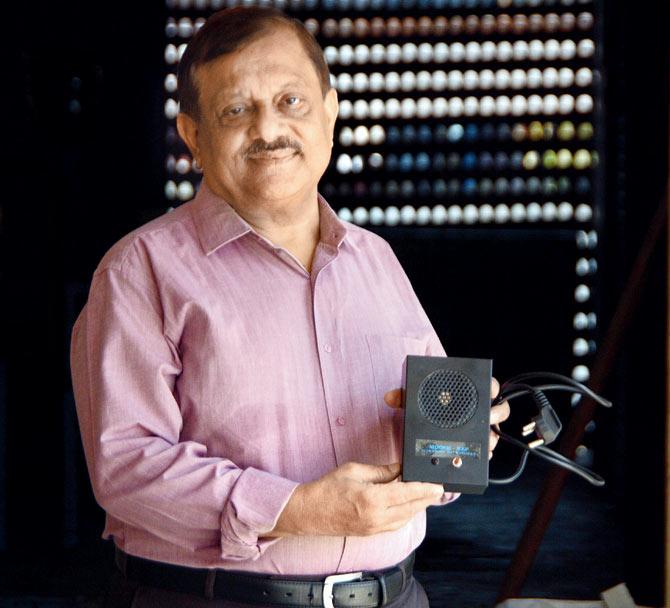

Navin Rohatagi, a partner at Sth Solutions, with their Ultrasonic Rat Repellant, Pic/Satej Shinde

The art of killing rats

Today, the menace in Mahim is under control. Machiwala and Dhala are immensely grateful to the NRKs, an army that's unique to Mumbai. "The system was established during the British period and so, NRKs have only been appointed in the original seven island wards. For instance, Matunga doesn't have one." And, while the BMC is currently looking at extending the service to other wards and is in search of contractors for the same, they have other weapons in their arsenal. Rat traps are provided free of cost to all residents of Mumbai who lodge complaints with the civic body.

Outdoor policy includes poison baiting. Every day, wheat pellets the size of vatana or peas are mixed with rodenticide and flavoured with garlic, oil and water and dropped into the many burrows across the city. "What should a city's rat population be?" asks Naringrekar when we ask if the city's rat population is under control. "On one day, we will check how many burrows exist in an area by filling up the ones we see with mud and coming back the next day to see if the mud has been shifted. The poison pellets are also dropped into the burrows so that rats are killed. The next day, if fewer burrows have been reopened, we can say that the numbers are 10 per cent lesser than what we started off with."

"

"

There are some places however where rats are welcome. For instance, at Rajasthan's Karni Mata Mandir, rats roam freely and are fed prasad. Pic courtesy Sanjeev Nayyar. Copyright www.esamskriti.com

Such activity, he says, is conducted ahead of the monsoon in areas prone to flooding. How many rats has the BMC killed in the last one year? Statistics point to 2,48,284 between January and December 2017. Naringrekar says the annual budgetary allocation for this exercise was around Rs 140 crore. "But, this is for the entire department and also includes staff payment, etc."

The city turns not just to the BMC but also to private pest control services in its battle against rodents. Prime among them is Rentokil PCI. While Rentokil is a global organisation with 100 years under its belt, PCI (Pest Control India) a household name in India, has been around for 64 years. PCI which operates across India gets, in Mumbai, an average of 15 calls per day for its Pied Piper Service (the name an obvious inspiration from the tragic tale of Hamelin written in 1812 by the Grimm brothers).

In just the first quarter of 2018, says Jayant Dandawate who heads operations at the firm, they have received a total of 1,280 PPS inquiries. While charges depend on the infestation and area, Rs 5,000 can be considered an average charge per service.

Mohan Rao, former joint director, Vertebrate Pest Management, Govt of India, and senior international consultant, FAO of United Nations

But, if BMC's armoury seems as powerful as the mighty Mughals at the height of their power, PCI seems to have the stealth and spy power of a modern-day FBI. Rentokill PCI's Managing Director Sam Easaw says, "In areas where there's no easy human access, we track the movement of rats using motion cameras. This works especially in secluded areas such as rooftops and false ceilings. The cameras will take pictures of access points so that once we identify these, we can take measures to deny the rodents access. We also use tracking powder which with UV light will show the movement pattern of rodents." Their bait stations, smart rectangular boxes, are tamper resistant so that only pests are caught and children or pets are not hurt.

The character of a researcher, in a 1974 best-seller, The Rats, a 196-page fictional piece on rats of London having mutated in both size and behaviour to attack humans, by James Herbert, discusses how the company he works for is now trying to use rats' acute sense of hearing - they locate their offspring in a field of corn by their high-pitched whistle - to root out rats from buildings by the use of ultrasonic sound beams. The researcher states in the book, it's still in the early stages.

Not in 2018.

While the technology has been available for 30-odd years, it's only been in the last few years that Goregaon based Sth Solutions, has been selling the Ultrasonic Rat Repellant. Explaining how it works, partner in the firm, Navin Rohatagi (who interestingly started his career with PCI), says, "This product is a repellant, it doesn't stop the entry of rats on the premises. They will come. However, they will not stay, as the sound - which at 50 mHz humans can't hear - will feel like hammering in their heads." Priced at R3,750 per unit, the repellant is effective in a 350 cubic feet area, say Rohatagi. But, there are several other factors: carpets, gunny bags, and clothes reduce the efficacy of the unit. It's most effective in places like server rooms, or restaurant kitchens where use of rodenticide or the sticky boards are not permitted.

While Rohatagi will not share how many units he sells in a year, he says the inquiries are so high that if they put an advertisement in the paper, "there will be a lathicharge at the office. Choohon se kaun pareshaan nahin hai, bataiye?"

Mooshik vahana

The pursuit of rats (or their eradication) has seen humans indulge in fairly counter-intuitive behaviour. In their 2015 book, Narratives of the Bombay Plague, published by Macmillan, Kalpana Swaminathan and Ishrat Syed recount the story of Dr Lewis Godinho.

"Godinho had been tracking sick rats in his locality, looking for a link between their passages and the route that the plague took. By December, he had become something of an expert in diagnosing early illness in a rat. It had changed his attitude towards rats. They were no longer vermin to be exterminated on sight, but omens, creatures of portent to be propitiated, made happy and healthy to ensure one's own health. He recognised this impulse as an ancient one that informed the customs of the land. With the coming of new religions these impulses had been condemned as superstition.

The first sign of plague in a rat was the change in its fur: brown, black or grey, whatever the colour, a healthy rat's coat was glossy, and well groomed. The shine went out of a rat when it became sick. It stopped grooming. It began to look dull and dishevelled.

Godinho had followed one such dishevelled rat through the lanes of Phanaswadi in Girgaum. Something had compelled it to change its address. Godinho followed the rat as it crossed the street and scampered along the gutter, nimbly leaping from threshold to windowsill, till it gained the eaves of a house at the end of the lane. Godinho kept watch over both houses the rat had occupied. Within a fortnight, both houses had the plague."

That was in the era of the Bombay Plague, an epidemic that left thousands dead in Mumbai. It was also a period, says Swaminathan, that changed the city dramatically. According to reports, between September 1896, when the first case was detected, till the rest of the year, the death toll was estimated at 1,900 people per week. With the setting up of the Bombay Improvement Trust, the city's population started migrating to newer areas instead of the close, festering gullies of the island city.

If following plague-ridden rats seems extreme, think of the plight of filmmaker Miriam Chandy Menacherry, who, after reading a newspaper article about 2,000 people applying for the post of BMC's NRKs, decided to document Mumbai's saviours. While discussing her admiration of the men (many of whom are post graduates and hope to land other government jobs through this) Menacherry, mentions in passing that she has a phobia of rats. "The first few days of tailing the men," she admits, "I was a liability. I was over wired up, nervous and wore high boots because when we began shooting, it was the monsoon. The boots themselves were a liability and filled with water as they waded through water." But, while she had boots, the men doing the dirty job had nothing. Not even gloves while picking up dead rats and piling them into gunny bags for counting later.

The most difficult part of the job comes during the Ganpati festival when rats, seen as the vehicle of Mumbai's resident deity, become too auspicious to kill. Ganesh, an NRK seen in Menacherry's The Rat Race, expresses conflict. Rohatagi says he visits Siddhivinayak temple and apologises in the ear of mooshak, Ganesha's companion, represented through a larger than life silver statue in the foyer, his wife, he says, admonishes him for killing rats, but he argues, "If we don't kill them, they will kill us."

Mythologist Devdutt Pattanaik, points out that our interpretation however, is not accurate. Ganesha, he says, is the Lord of Prosperity. So why would he choose a vahana that's a destroyer of crops? "He is seen sitting on a rat and on his waist is wrapped a snake. And, what does a snake eat?"

Where does Mumbai stand?

A read through Room 000 is enough to scare you into being afraid of every rat and squirrel (yes, they can carry the plague bacteria, too). So, if so much is being done on ground, why aren't there any results?

Naringrekar and Easaw put it down to the lack of hygiene in the city. Throwing garbage and debris in the open provides rats with both, shelter and food. Why won't they prosper? "Kolkata has a similar situation, but Mumbai is far worse. If you see rats roaming in the daylight, you know the situation is out of hand."

Naringrekar says, every day rats picked up from various wards in the city are checked to see if they have the plague virus. That not a single case has been seen proves that the situation, at least for now, is under control.

It's a granny's tale. A colleague recalls how her mother would make her brush her teeth at night under the threat that, if she didn't, a rat would climb by her bed and gnaw her teeth to get to the sweets lodged inside her mouth.

Perhaps, all that Mumbaikars, need to do is keep their teeth and the city's gullies clean. Really, clean.

Also read: Eknath Khadse: I smell a rat in Mantralaya's pest control scheme

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!