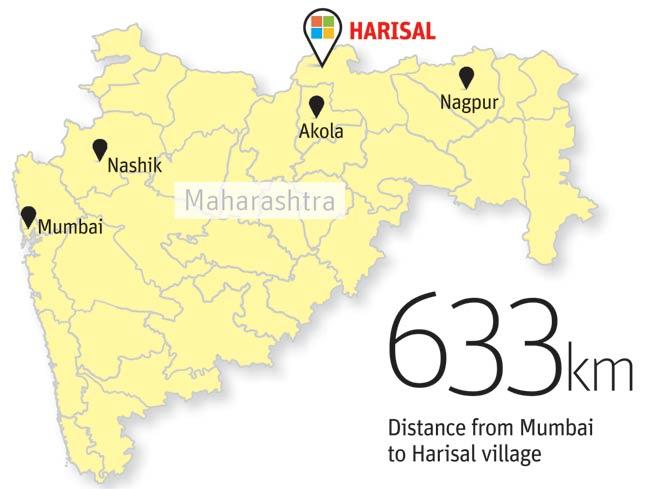

The state and Microsoft want to make Harisal in Melghat, India's malnutrition capital, the country’s first 'smart village'. We travel to the hamlet to see what it really needs

On the state highway to Melghat, you will not find Harisal on milestones or road signs, not even when you are just 10 km away. It comes up suddenly — a cluster of houses, a prominent blue Bank of Maharashtra board, and a fading green sign that says ‘Harisal’, which is a “medium-sized village” as the 2011 census described it.

On the state highway to Melghat, you will not find Harisal on milestones or road signs, not even when you are just 10 km away. It comes up suddenly — a cluster of houses, a prominent blue Bank of Maharashtra board, and a fading green sign that says ‘Harisal’, which is a “medium-sized village” as the 2011 census described it.

ADVERTISEMENT

Harisal village, which has been a nondescript adivasi settlement, finds itself on the Digital India map. Pics/Sameer Markande

Until a couple of months back, Harisal was a nondescript adivasi settlement left to its devices. Now, it is all set to become the first “smart village” in the country, and “online” is the buzzword here, a magical string of syllables on the lips of its 1,479 residents.

Also read: Maharashtra to get 50 smart villages by 2016-end

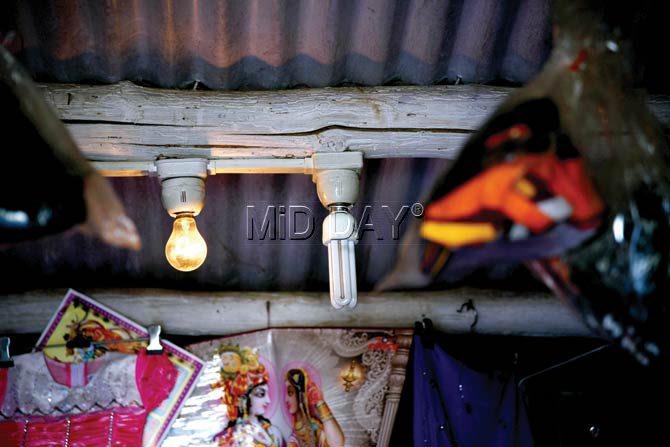

A lone bulb barely lights the readymade clothes shop. The village faces around 14 hours of load-shedding every day

The buzz started on September 14, when the village received rather unusual visitors — Microsoft India head Prashant Shukla, district collector Kiran Gitte and the CMO’s IT chief Kaustubh Dhawase — as a rite of initiation into the mothership called Digital India.

A mobile tower is supposed to be erected at this spot

Two weeks ago, Maharashtra Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis, who had visited the village last year, announced at Microsoft’s Future Unleashed event that Harisal will be the first-of-its-kind “smart village”.

“Technology will be the means to solve problems of health, education, skill development and employment,” as collector Gitte puts it. Mobile connectivity, a Wi-Fi zone, a digital centre, cashless markets, health cards and telemedicine are on the agenda to transform Harisal, according to officials.

Kaustubh Dhavse, officer on special duty (IT) in the Chief Minister’s Office, told mid-day, “The idea of village smartness was the CM’s concept to bring villages to the mainstream. The region has all core infrastructures in place but the people need to be made aware of the benefits they can derive from it.”

He added that Harisal was an ideal place as most of population had smart phones and television sets that connected them with the world outside. But over at Harisal, villagers draw our attention to a lone bulb that barely lights the readymade clothes shop.

The village faces severe load-shedding — six hours in the night and eight hours during the day — and even when there is power, it is just enough for a low-wattage bulb. Running televisions at home and motor pumps in the field invite strict reprimands; villagers say there is no water supply.

Jayshree Kharve, an ASHA worker at one of the three aanganwadis in the village, said the things the aanganwadi needs the most are a compound wall, water supply, and pensions for the workers — none of which are to do with technology.

In fact, looking back at Dhavse’s remarks, it looks like Harisal will only now really get the so-called “core infrastructure” under the Digital India plank. The sarpanch Bhau Chipu Dhikar, an adivasi from the Melghat’s predominant Korku tribe, believes “online” will be the doorway into “sukh suvidha” (comfort and amenities).

The quiet ex-forester does not own a mobile phone and has never seen a computer. For him, Digital India is “something the American sarkar has brought to India.” Thanks to Digital India, Dhikar is optimistic that his village will become more like a city, and that his sons, who are high-school pass-outs, will get a steady employment rather than farming.

Another villager, Deepak Nagle, 28, is one of the 14 members in an all-male nodal committee of villagers formed under the smart village plan. Nagle will be trained in computer basics, and will in turn teach other villagers. Nagle, who stopped at high school, works as a driver, shunting between Harisal and Parathwada, the nearest developed centre at the foothills of Melghat.

He has a mobile phone number, but with no way to charge his phone, it is pretty pointless. Nagle has other pressing concerns too. The nearest undergraduate college is in Dharni, 26 kms away, so pursuing engineering or medicine is not an option for every Harisal student. Buses do not ply frequently into Harisal either.

“There are new technologies in education that we can be part of if we have Internet. Microsoft has already mapped our houses using GPS, and soon farmers will be able to ask their queries online,” he says.

Power struggle

While these ideas look great on paper, electricity is a major issue for Harisal. The town Dharni, which is also the taluka under which Harisal falls, has 24x7 power supply.

So does the neighbouring hill-station of Chikladhara, a tourist destination. But in Harisal, the bank, fitted with an inverter and solar panels, is an anomaly. The most solar energy that is domestically used in Melghat is in the form of lanterns, provided by the Forest Department.

Dhikar says, “We have been conducting morchas and fighting the load-shedding problem for the last four years. We had electricity supply before that; but with decreasing ground water levels and an increase in the number of bore-wells, we started facing this problem.” Another villager chimes in, “But families here still get a monthly electricity bill of Rs 400.”

Asked about this, Collector Gitte said power supply will soon be directed from Nepanagar in Madhya Pradesh. Sources on the ground, however, added that these talks have been on for over a year without any results.

Gitte and Officer Dhavse added BSNL has finished laying fibre optic cables and Indus will erect a mobile tower (even as one installed by Reliance stands defunct) right outside the panchayat office in a month’s time.

Dhavse, who has worked for top corporate companies before joining Team Fadnavis, said the information highway would be ready for transmission anytime soon.

More than just digitisation

At the Future Unleashed event in Mumbai, Fadnavis – speaking in the presence of Microsoft boss Satya Nadella – said: “The lack of nutrition, coupled with genetic health problems, and the lifestyle of people have to be changed to make it more healthy and connected with the mainstream.”

District Health Department figures show the Dharni taluka in Melghat recorded 158 deaths under the age of one just in April and May, though villagers don’t make much of it. The deputy sarpanch Ganpat Babuji Gayan, in fact, claimed malnutrition figures have come down considerably in the past few years.

Vandana Krishna, director general for the Rajamata Jijau Mission, explained Harisal’s attitude thus: “Local people have become cynical. Melghat has been so over-exposed as a malnutrition centre that villagers have reached a saturation point. After all, Melghat is not the only hotspot. Gadchiroli, pockets of Nashik, and Nandurbar are more backward, but with fewer NGOs operating in these places.”

In 1996-97, the area recorded more than 1000 deaths under the age of six, as compared to 2013-14, when a little more than 400 deaths have been seen. Explaining how digitization will help curb these deaths, Collector Gitte said, “While child mortality rates have been on the decline with the help of anganwadis, midday meals, etc, it is still a challenge to bring down Infant Mortality Rates (IMR). The challenge is to bring pregnant mothers well in time to hospitals and not lose them during transportation.”

Baby warmers in ambulances, mobile-connectivity for ambulances and tele-medicine are some of the ways by which the smart village will combat IMR and (Maternal Mortality Rate) MMR, he said.

While Harisal gets its fair share of basics along with digitization, the plan is that 51 smaller villages within a 15 km radius will benefit from this. Gitte added that locals will be taught improved farming techniques using digitally-accessed advice in weather patterns, soil quality with the aiming of increasing the output of soybean and tendu leaves, which is used to make beedis.

Dr Ashish Satav heads NGO Mahan, established in 1998 to improve health for adivasis in Melghat. He said technology against malnutrition will work only with the right human intervention.

In a report he co-authored in May, Satav recommended home-based child care, preventing under-reporting of malnutrition cases, building child development centers and nutritious kitchens. Satav also said newer diseases like tuberculosis and heart attacks were on the rise in the community and that digital initiatives should look at ways to tackle these, too.

Similarly, Krishna said the greatest boon digitization can offer the village is to take aanganwadi reports online. Currently, the reports show mere numbers, and have no details. “The reports do not tell you what is happening to each child but show bulk figures. Digitising records will help us to track the progress of each child, make comparisons, and minimise the under-reporting that is predominant in these records.”

Satav added that while it is good to focus on Harisal, some of the other worse-off villages should not be forgotten. “Harisal, with its PHC and an ambulance on call, is not the worst off among villages with malnutrition in Melghat,” said Satav. “It is on the highway and has access to health amenities. Kokmar, a hamlet 25 kms away from Harisal, on the other hand, has seen the worst of inaccessibility to basic healthcare.”

Substandard delivery kits (which include razors and sickles), diarrhea-related deaths, misbeliefs regarding check-ups are predominant in Kokmar. The Korku tribe, say experts, have been a challenge to health workers, since they are particularly superstitious. The tribe usually resorts to witch-doctors and quacks, who dispense amulets and taveez.

‘Jhaad-phoonk’ is the first option; approaching the PHC is the last. Women have as many as 12 children. Dr Satav says, “Making a hamlet like Kokmar, which has 14 kms of kaccha road, into a smart village will be the real success story. Harisal is not the real representation of Melghat.”

The 30 houses in Kokmar have a monthly income of less than Rs 3000 and are mostly Korku. Harisal, on the other hand, is not your average adivasi village since it has several migrants, including Marathi-speakers and Muslims. “People from Kokmar have no market facility, no buses and are exposed to quacks. There is absolutely no electricity. Is Harisal then a replicable model?” asked Satav.

Needed: Smart solutions

Some of the proposed technological initiatives have already been tried out with varying degrees of success. Advocate Purnima Upadhyay, from NGO Khoj, a voluntary organization in Melghat, pointed to the failure of telemedicine in the Semadoh, 24 kms away from Harisal, and on the highway as well.

About eight months before the Fadnavis government came to power, the villagers were given telephonic access to doctors in urban areas, but with no mobile phone coverage, this plan died a quiet death. Moreover, the medicines prescribed by the doctors were not stocked at the PHC.

“The top-down model is not going to work and the basics need to be improved. The ideal way to go about with digitization is to do is simultaneously in five villages, with different indicators and then analyse different success rates,” she said. Her colleague Adv Bandu Sane added, “Instead of waiting for so long to bring in cellphone towers to enable calling ambulances, why weren’t landline facilities made available years ago?”

On paper, tele-medicine is a zero-cost solution, according to Sam Pitroda, who launched the Centre for the Development of Telematics as part of a similar initiative by the Rajiv Gandhi government in the 1980s to take telecommunication to the country’s farthest corners.

“All you need is access to a qualified doctor. Khatam,” he said. What Pitroda is wary of, however, in this “reasonably sound plan” is a tight handshake between the Maharashtra government and Microsoft. “We don’t want proprietary software. It should be open source, which people can further develop.

Instead of just hardware and software getting pumped into a village, we need NGOs, activists, women, social scientists, anthropologists and psychologists to be part of this model. There has to be a balance between customization and standardization,” he says.

Pitroda said connecting panchayats is the building block of digitization, but it then has to be planned well, both top-down and bottom-up. He uses the term interoperability — a way of making sure that various institutions are linked together.

“The old ways of doing things have become obsolete, especially with the rise of social media. What do you think will happen if you put a whole village on Facebook,” he asked. Admittedly, Harisal is just a pilot project, based on the successes of which 11 more clusters will be digitized in the area.

And pilot projects and experiments are great, says Pitroda, as long as there is a “tough understanding” of the needs of rural Maharashtra. “A tribal may not know the possibilities of digitization, but he knows what he wants. If you spend Rs 2 crore then what do people get?” asked the telecom engineer.

State speak

Kaustabh Dhavse, officer on special duty (IT) in the CMO and the nodal officer for the Harisal project tells Dharmendra Jore how the government will transform the village

Q. Why Harisal?

A. Harisal has the dubious distinction of being the malnutrition capital of Maharashtra. It has very peculiar demographics. Its social indexes are highly negative and despite being blessed with ample natural resources the area suffers from a plethora of issues. The issues are solvable and only require intent and government will. When we met the people of Harisal, their steely resolve to work to fix the issues inspired us and made it the right choice. The CM believes that when an effort becomes people's movement its success is guaranteed. Our strategy is similar to what we did in Jalayukt Shivar (rural water conservation programme).

Q. What changes can Harisal expect in the coming months?

A. 1) Self-sufficient and Sustainable Village economy with enough resource creation, 2) Bringing Harisal people to the mainstream by providing them access to the Information Superhighway, 3) To bring the entire village on the banking system with 100% compliance to PM Jan Dhan Yojana, 4) PDS, Education, PHC, Tribal/EBC (other backward class) benefits ecosystem will be created, 5) Village GDP and Socio Economic Growth Quotient will be measured and monitored on periodic basis. Efforts to drive it up will be taken. Focus is to drive economic growth, and 6) Skill Development initiatives with mahakaushalya.com

Q. How will the Digital India programme help put an end to malnutrition in Harisal?

A. Malnutrition is a byproduct of a system that does not organise itself well to solve the issue. Policies earlier were like band-aid. It never looked at the problem in detail to see what causes this menace. We were able to dwell deeper and basis data co-relate factors affecting health to impoverishment and ignorance. It is like a vicious cycle. Malnutrition problem is similar to the farmers suicide issue. The problem is systemic. Our design philosophy which primarily rests on driving up economic activity, empowering villagers and giving them clarity, literacy and access to govt services will kill this menace once and for all. Several thousands of crores have been spent to drive away malnutrition without understanding the problem in detail. The issue when understood completely now is in the process of resolution.

Also read: Microsoft to develop 'smart villages' in Maharashtra

Q. What kind of support is Microsoft receiving from the Maharashtra Government?

A. State and Microsoft are in a partnership to make Harisal the first Digital Village in the country. MS will invest capital and GoM will provide all support. The day this is ready, it will become a national example. What technology can do to common lives and how it can solve complicated issues, our implementation will show.

Q. Harisal does not have continuous power supply. How does the government think Microsoft is going to deal with that?

A. Power will be continuous through renewable sources. There might be a short-term issue till we get our act together, once our core (conventional) and non-conventional power sources are in place, the village will shine like never before. Villagers deserve to be part of the economic growth story. We are committed to deliver this to them.

1,479

Population of Harisal village in Melghat in Amravati district

158

Malnutrition deaths in Harisal in April and May

1,000

Number of children below six who died in Harisal in 1996-97. This has come down to 400 in 2013-14.

Rs 3,000

The monthly average income of Kokmar village, which is just 25 km from Harisal

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!