The hero of the 1971 India-Pakistan war ended the conflict in 13 days, browbeating his Pakistani counterpart with 30,000 men into surrender despite himself having only 3,000 men

“I am very proud to be a Jew, but am Indian through and through. I was born in India and served here my whole life; this is where I want to die.”

“I am very proud to be a Jew, but am Indian through and through. I was born in India and served here my whole life; this is where I want to die.”

ADVERTISEMENT

General Jacob-Farj-Rafael “JFR” Jacob got his wish this morning.

I had spoken to him briefly on the phone on December 28, a few days before he was admitted to the Army Research and Referral Hospital in New Delhi with acute pneumonia. Sounding frail and disoriented, he enquired about my family. When I expressed concern over his health, he declared, “I am just an old soldier, waiting to fade away.”

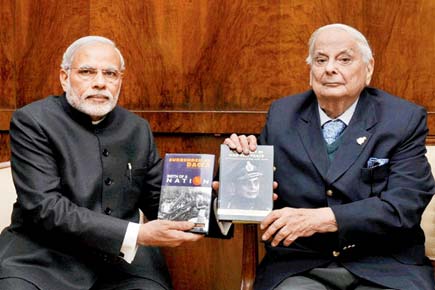

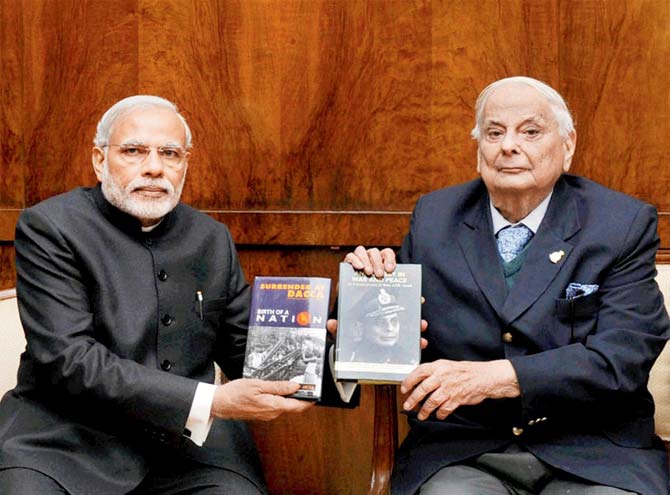

Prime Minister Narendra Modi with Lt General (Retd) JFR Jacob at a function in New Delhi in Dec 2014. Pic/PTI

Since he had said the same thing in some other recent conversations, (I used to call him at least once every month, if not more), I reassured him that he would be fine, and promised to catch up whenever I was in Delhi next. But the Gods had other plans.

I first met General Jacob in the winter of 2006, while I was commissioning stories for a web-series recalling the 1971 India-Pakistan war. I knew nothing much beyond the fact that he was a key player in that war.

That he had gone to Africa in World War II as part of the British Indian Army to take on the formidable Erwin Rommel and his Afrika Korps, (but his brigade landed too late) and then fought against the Japanese in the Burma campaign. And that when the British left India, he decided to stay on in the Indian Army, taking part in the 1965 war and then the war which led to the dismembering of Pakistan and the birth of Bangladesh.

Given that he was on the wrong side of 80, I was expecting a doddering old man whose ramblings I would have to decipher and turn into a passable story. But sitting in his small living room in New Delhi’s Som Vihar, cluttered with artifacts from around the world, I was struck with the man’s incredible energy, strength and phenomenal memory.

Dates, names, numbers, came effortlessly to him as he took me back 35 years to the only war that independent India unequivocally won, stamped by the only public surrender in military history. A surrender that he had single-handedly negotiated in Dhaka, then the capital of East Pakistan.

In 1971, India was reeling under the influx of Bengali refugees from East Pakistan fleeing a genocide by the Army from the west, bent on squashing Bengali protests against the imposition of Urdu as the official language, among other things.

When war was finally declared after Pakistani air strikes on Indian airbases in the west on December 3, India under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and her army chief, Sam Manekshaw, were well prepared.

Lt General JFR Jacob was then head of the Chief of Staff, Eastern Command, reporting to Lieutenant General Jagjit Singh Aurora, General Officer Commanding-in-Chief of the Eastern Command. As Indian troops entered East Pakistan, General Jacob, disobeying orders to capture and consolidate each town before moving to the next one, headed straight for Dhaka. When he reached the outskirts of the city, where the Pakistan Army and Mukti Bahini rebels were battling in the streets, he had barely 3000 men.

General AK Niazi, Governor and Martial Law Administrator of East Pakistan, had 30,000.

Armed with a hurriedly drafted surrender document, which was yet to be cleared by the Indian government, Jacob brazenly entered Niazi's headquarters to demand a surrender.

“General, I assure you if you surrender in public, accept these terms, we will look after you and your men. The Government of India has given its word and will ensure your safety and that of your civilians. If you do not, then we can take no responsibility,” Jacob recalls telling Niazi.

"He (Niazi) kept talking until I said, General, I cannot give you any better terms. I will give you 30 minutes. If you don’t comply I would have no option but to order resumption of hostilities.”

He walked out, and paced outside Niazi's office.

On his return after half-an hour, “Niazi kept quiet. I walked up to him. The document was on the table and I asked him: General, do you accept this document? I asked him three times but he didn't answer. So I picked it up. I said, I take it as accepted.”

On December 16, 1971, General Niazi signed that surrender declaration on the grounds of the Ramna Race Course before Lieutenant General Jagjit Singh Arora. Thirteen days after it started, the war was over. Bangladesh was born.

Later, General Niazi would admit that he had signed the surrender document despite having more troops because “Jacob bullied me”.

(A retired Pakistani General once confessed to me that apart from the defeat “at the hands of Hindustan, the fact that the Indian negotiator was a Jew was like sprinkling salt on an open wound.”)

General Jacob retired in 1978, and later joined the BJP, becoming Governor of Goa and later Punjab.

After the meeting in New Delhi, the general and I stayed in touch, and the only thing we ever disagreed over was his contention that “Manekshaw and Aurora” had hogged all the credit for the war, whereas it was he who had negotiated the surrender on his own, and that too by directly disobeying orders. I would argue that in any war, the commander was the man who would get credit for a win or a loss, regardless of how well or badly his team played.

“No,” he would mutter. “Manekshaw had the Parsi lobby, Aurora had the Punjabi lobby. I never had a Jew lobby.”

But barring that chip on his shoulder, the general was a rare breed, an upright, honest man who selflessly bequeathed his considerable personal wealth (His family ran a large, prosperous business in Calcutta) and possessions to charity and the Indian Army, which, he once told me, “was more than a family to me.”

When I once pointed out an article that referred to him as the “hero of the 1971 war”, he modestly replied: I’m no hero. I’m just a proud Indian.”

On my bookshelf, I have autographed copies of his two books, his autobiography, “A Odyssey in War and Peace,” and “Surrender at Dhaka.”

“To Ramananda, …an old friend,” says the inscription on the former.

Goodbye, my friend. Peace be with you.

The author is a foreign and strategic affairs analyst, and Consultant Editor with Indian Defence Review.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!