Sakshi Dahavare, who dreams of being a doctor, is back at school after having to leave due to lack of documentation, because of the relentless efforts of one woman. Civic school teachers across the state have emerged backroom heroes of the government’s Mission Zero Dropout campaign

Primary teacher at Chembur Education Society, Spruha Indu, has been helping dropouts in the neighbourhood to get enrolled again. Sakshi Dahavare, 12, who lives in a one-room home in Lal Dongar with her mother and brother, returned to class after 2 years thanks to Indu. Pic/Atul Kamble

Glancing from behind the rickety door of his one-room tenement in a discreet corner of Dharavi, 13-year-old Vicky Ramkeval Gautam makes a revelation. A native of Uttar Pradesh’s Basti district, Gautam wants to become a doctor, so that he can help solve the dearth of medical practitioners in and around his village. Gautam is a Class VIII student at Dharavi Kala Killa Municipal School.

ADVERTISEMENT

Two years ago, his dream to pursue medicine went awry when COVID-19 struck. As the national lockdown was imposed in March 2020, Gautam, much against his wishes, was forced to return to UP with his younger brother and mother, whose roadside food kiosk business in Dharavi area took a hit. His father is a small time plumber back in UP. The initial days were tough—the family lived in isolation, as residents kept a distance, fearing that they’d contract the disease from the ‘urban returnees’. Gautam slowly began making new friends, whiling away time outdoors. But all through, he missed school immensely.

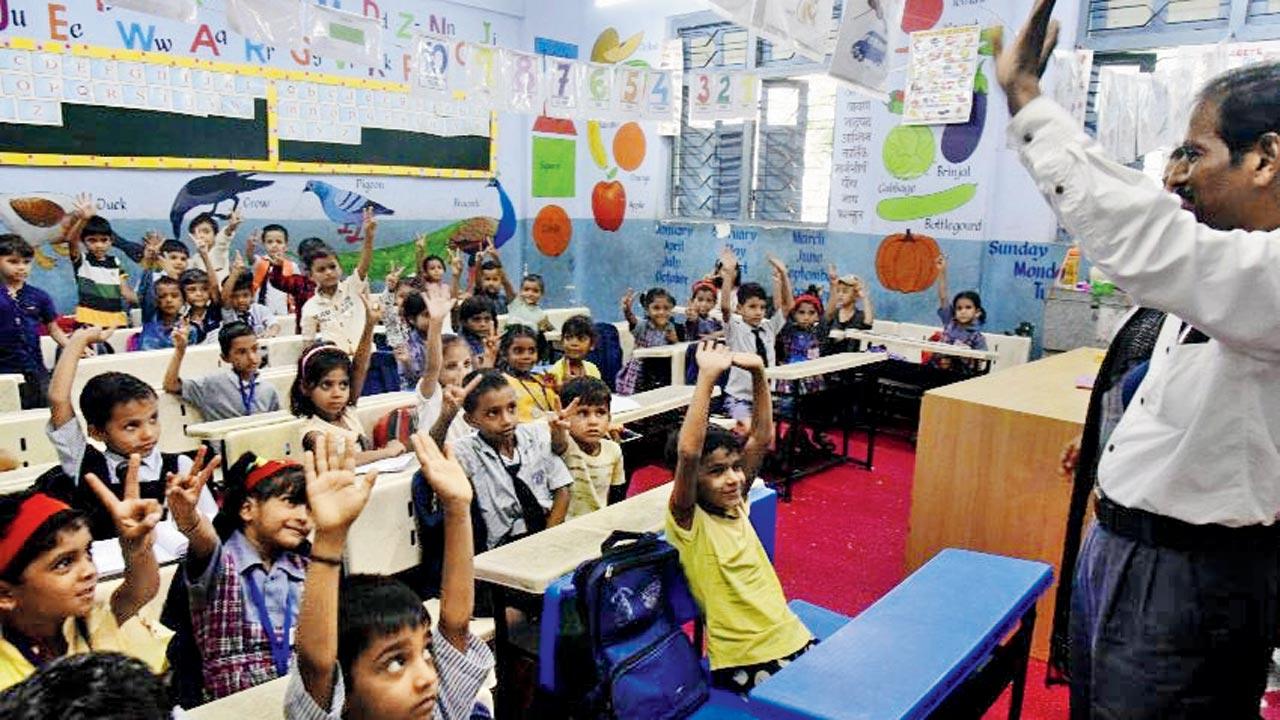

Dharavi Kala Killa Municipal School had just 190 children in June. After initiating the Mission Zero Dropout campaign, the numbers rose to 266 children in the senior classes and 72 children in the junior classes

Gautam is among thousands of children from low-income backgrounds, who were forced to take a break from schooling due to the financial constraints that the pandemic presented families with.

While education warriors are working overtime to undo the damage and minimise the education gap across the spectrum, teachers in Mumbai’s civic-run schools have been going beyond their brief to ensure that students from the “dropout list” get listed on their attendance registers once again.

Vicky Ramkeval Gautam, 13, returned to his BMC-run school in Dharavi after a pandemic break when he had moved to his ancestral home. He says he wants to become a doctor because there are hardly any medical practitioners in his village in Uttar Pradesh’s Basti district

This effort is part of the Maharashtra Department of Education’s Mission Zero Dropout campaign, which aims to re-admit kids who quit schooling in the last two years. The month-long campaign carried out from June 23 to July 20, targeted children between three and 18 years of age. According to the order issued by the Education Department, the campaign focused on drop-outs in and around Mumbai and parts of Maharashtra, including Kolhapur, Solapur, Satara, Pune and Ahmednagar.

Malti Madhukar Tonape, deputy education officer at the BMC and nodal officer for Mission Zero Dropout, told mid-day that about 6,227 children had dropped out of schools in Mumbai during the pandemic. “Some had not been coming before the lockdown as well, but the majority dropped out during COVID,” she says.

Jayandra Babu Kadam and Kavita Vilas Mahale, teachers at Dharavi Kala Killa Municipal School, visit homes every day like this one in Dharavi, to convince parents to send their kids to school. Pics/Atul Kamble

As part of the campaign, municipal school teachers were asked to visit every nook and cranny of the city, slums, padas in forests, railway and bus stations, and factories, to trace children, who had dropped out of school.

“We also made efforts to provide bus passes to children who had migrated to areas further away from their schools, and facilitated admission into BMC schools near their homes,” she adds.

Dharavi Kala Killa Municipal School’s head teacher Sunil Somanath Bhangare has been instrumental in getting kids back to class; (right) Sakshi’s mother Vandana Dahavare lost her husband and works as a domestic help to bring up two children

Back in Dharavi, teachers Jayandra Babu Kadam and Kavita Vilas Mahale continue to visit the slums every day, lifting stained curtains that guard one-room homes from the bustle outside, looking for any child who is yet to join school. Their voices echo in the desolate alleyways as they cajole parents, “School mein daaldo na, khane ka bandobast bhi hum karten hain, kapde bhi detey hain. Hamara school yahin paas mai hai. [Enroll your child in school. We provide books, food and uniforms. Our school is just around the corner].”

Kadam and Mahale are part of a team, which under the guidance of head teacher Sunil Somanath Bhangare, has been instrumental in getting kids back to the Dharavi classroom. “On June 15, our strength was 190 children. On July 26, it rose to 266 children in the senior classes and 72 in the junior classes. These numbers include both dropouts and new admissions,” Bhangare shares.

Spruha Indu, a municipal teacher at the Chembur Education Society Primary School, with her former student Sakshi Dahavare, 12, a resident of Lal Dongar in Chembur. After she was forced to drop out of school due to lack of documentation papers, Indu helped her secure admission to a Marathi-medium municipal school

Long before this campaign was introduced, a handful of civic teachers were already going the extra mile to ensure students continued schooling.

Spruha Indu is a municipal teacher at the Chembur Education Society Primary School. Since 2008, she has been working on re-enrolling dropouts. Indu tells mid-day that she has received support from her school principal Vitthal Kamble, who has been encouraging the faculty to visit Siddharth Nagar, Lal Dongar and Amar Mahal signal areas in Chembur, before classes commence, to look out for dropouts. Indu has managed to get seven to eight kids back to school every year. So far, 63 children have re-joined school because of her persistence.

Sheikh Sharifa, who teaches at a BMC school in Borivli East, has been ferrying four of her students to and from their Mira Road homes in an auto-rickshaw daily. She took on the responsibility after their parents moved from Borivli to Mira Road due to COVID-related financial conditions

Mid-day’s writers accompanied Indu to Lal Dongar early last Tuesday afternoon. “The last time I came here, it was raining heavily,” she shares. As we walk through the labyrinth of hutments, we run into one of her success stories— her former student, who with Indu’s help, had joined college and is now interning at Sion Hospital to become a medical practitioner.

After walking for 20 minutes, we arrive at Sakshi Dahavare’s home. The 12-year-old girl, who Indu says is “a bright student”, wishes to be a doctor . She studied in Indu’s school till class IV, but in the absence of proper documents, couldn’t secure admission to secondary school.

BMC school teacher Zareena Parkar during a visit to a slum near her school, encouraging parents to re-admit their children. Parkar requested local mosque management committees to make announcements after Friday sermons, urging parents to send their children back to school

Lack of documentation is one of the chief reasons why kids aren’t able to secure admission or are forced to leave midway. “We have noticed that domestic disputes, violence, separation of parents and non-cooperation with one another create a roadblock in the documentation of children.” Most children do not have basic documents like a birth and caste certificate, Aadhar card, and ration card.

In Dahavare’s case, her neighbours pulled some strings, and sent her to another school. But the problems persisted, with the school threatening to file a police complaint over non-payment of fees, Dahavare’s mother, Vandana, tells us. A single parent of two children, Vandana works as a domestic help and leaves home early in the morning. Sakshi manages the home chores, while her mother is away. In June this year, she joined a Marathi medium school, which is a five-minute walk from her home. Sakshi’s elder brother who is in the ninth grade was fortunate enough to not have faced any difficulty in his education.

Zareena Abdul Rehman Parkar and Sheikh Sharifa, teachers at a BMC school in Borivli East, were able to bring back children who had migrated to Vasai and Kashigaon. “We asked the BMC to provide bus passes and train passes for them, so that they could travel without placing a financial burden on their families,” Parkar says.

Indu has helped connect the parents with NGOs and donors who can help with uniforms, books and fees.

At Parkar’s school, the overall student strength fell to 79 in 2020. Today, they have 189 children. “I assured the parents that the BMC would take care of all requirements, from uniform to stationery.”

Another growing concern is the demand for English-medium schools, which incidentally, only adds to the drop out numbers. “Many parents want to send their kids to an English-medium school, but it doesn’t always work out. Children can’t cope because the environment and language at home is different,” explains Indu.

Irregularity in attending classes, Indu explains, is equivalent to being a dropout. “Most parents leave for work and the kids are alone at home. The children don’t understand the importance of school and tend to miss days, even weeks and years at a stretch despite having a seat at school,” says Bhangare. To ensure that this doesn’t happen, Indu does regular in person follow-ups with parents and students. In cases where both parents are working, there is no one to drop the child to school. “We provided a bus service, but the parents were unable to pay even a small fee,” says Indu.

Sharifa, a breast cancer survivor, has taken on an unprecedented responsibility. When a few students from her school shifted base to Mira Road due to COVID-related financial trouble, she decided to ferry them to and from school. “Now, every day, four kids who moved to Mira Road, accompany me in an auto-rickshaw to school and back.”

In September 2020, nearly four months after the BMC started online schooling, it opened the classes for students across the state. The stop-gap provision, available free of charge, was aimed at ensuring that the benefits of virtual schooling trickle down to every student across Maharashtra.

Bhangare says that although BMC’s online classes were quite successful beyond Mumbai, several children in his school, did not have the means to access virtual education. “Many didn’t own a smartphone. Even those who had one, struggled to access these classes. We had to recharge their mobile packs.”

Mahale adds, “We tried to provide smartphones to children, with the help of NGOs. We also started a YouTube channel where live lessons by BMC teachers were uploaded as recorded lessons, so that when these students would have the luxury of uninterrupted Internet, they could access the lessons at their convenience.”

Teachers, like Kadam, also taught students through text messages and over phone calls. “Many students who went back to their villages did not have smartphones. We got their contact details from the neighbours and taught them over a regular phone call.”

To negate parents’ fear of COVID once offline classes resumed, online parents’ meets were organised by the Dharavi Kala Killa Municipal School. “Through the meetings, we made parents understand the importance of education and that we were taking all COVID precautions. All our teachers were fully vaccinated, followed social distancing, and use masks and sanitisers,” Bhangare says.

Back in October 2021, when offline classes were to resume, Parkar spoke to local mosque management committees and asked them to make announcements after Friday sermons, urging parents to send their children back to school. “I distributed handmade fliers informing people about the COVID protocols that were being followed. We also showed people videos and photographs of sanitisation activities at the school premises,” she adds.

Indu went one step ahead. She created awareness among single parents, especially single mothers, about the need to be self-independent. “I urged them to learn stitching, or attend a beauty parlour course… just anything that could help them earn. If they feel empowered, so will their kids.”

6,227

No. of students dropped out of municipal schools in Mumbai in the last two to three years

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!